TRILOBITE FOSSILS FOR SALE

What Is A Trilobite?

Trilobites were a very diverse group of extinct marine arthropods. They first appeared in the fossil record in the Early Cambrian (521 million years ago) and went extinct during the Permian mass extinction (250 million years ago). They were one of the most successful early animals on our planet: over 25,000 species have been described, filling nearly every evolutionary niche. Due in large part to their hard exoskeletons (shells), they left an excellent fossil record.

Trilobite Anatomy

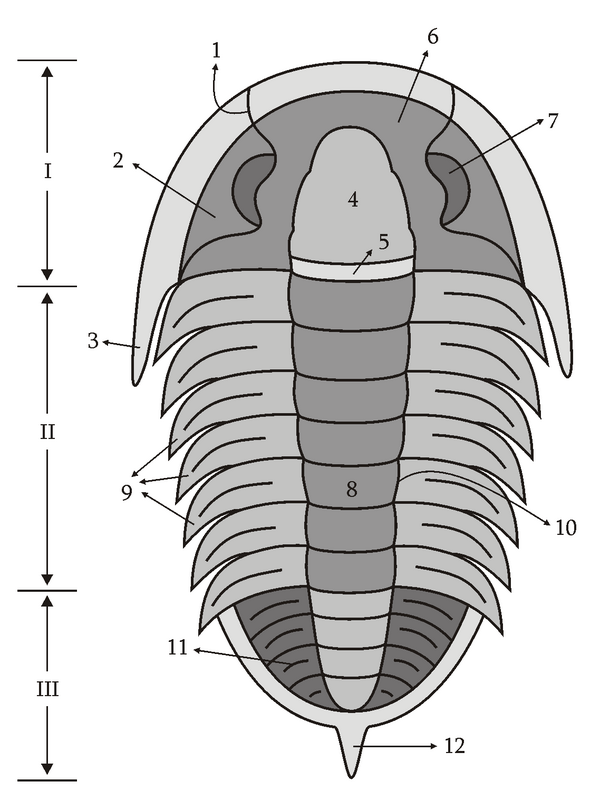

The name “trilobite” is Latin for “three-lobed body.” This title refers to three main sections of the trilobite: a central lobe and two pleural lobes along the length of its body. However, a trilobite has three main body sections: the cephalon (head), the thorax (abdomen), and the pygidium (tail). Beneath a trilobite's tough exterior are three pairs of legs for the head, and paired legs for each pleural groove. Trilobites have distinctive biramous (double-branched) appendages.

Trilobite anatomy sketch drawn by Muriel Gottrop

I – Cephalon, II – Thorax, III – Pygidium, 1 – Facial suture, 2 – Librigena (Free Cheek), 3 – Genal Spine, 4 – Glabella, 5 – Occipital ring, 6 – Fixigena, 7 – Eye, 8 – Axial lobe, 9 – Pleures, 10 – Dorsal line, 11 – Ornamentation, 12 – Posterior spine

A trilobite has many distinct body parts with specific names, forms, and functions. The website www.trilobites.info, has a wonderful morphology map of both the under and upper sides of the exoskeleton: https://www.trilobites.info/trilomorph.htm

Feeding strategies are inferred from anatomical features. The glabella, an area of the cephalon that is usually more bulbous, contains the stomach. After the stomach follows the alimentary canal to the anus. Trace fossils, unique cephalon and hypostome morphology, and even a few glimpses at appendage structure are the clues scientists have to determine the ecological niches of these “bugs.”

The exotic skeletal structures are both beautiful and functional. Some trilobites have predatory hypostomes likely designed to hold, pin, or break up prey. Tiny spines on appendages imply that such spiny structures acted as little sweepers to move food toward the mouth. Some features on these appendages imply filter-feeding strategies instead.

Feeding Strategy

Trace fossils such as little troughs in ancient mud and feathery tracks imply that some species were mud scavengers. Streamlined body design or flowing spines imply an ability to swim or float efficiently for hunting or filtering. Individual trilobites have been found buried while resting just outside worm burrows, implying that some species may have hunted burrowing animals and possibly used their specialized appendages or hypostomes for such predatory activity.

Features such as eyestalks and/or 360-degree fields of view suggest a life history beneath the mud, where food or danger lurked from above. Many species have turreted eyes and other spiny features that may have been suited for life on muddy bottoms. At least one species was able to live and presumably feed in low-oxygen environments.

Molting

Trilobites molted their exoskeletons in a process called ecdysis. Since trilobites molted like other arthropods, they needed a means to remove themselves from their exoskeleton when it became too tight. They did this through their crescent-shaped head shields. These shields disintegrated into individual parts: the cranidium, encopassing the globella and free cheeks; a rostral plate; and a hypostome (a stiff structure associated with the mouth).

First, the animal found a relatively safe place. Trilobites were soft, delicious treats without their shells! Hormones likely stimulated the molt process. In insects, a sudden release of prothoracicotrophic hormone in the corpora cardiaca causes the prothoracic glands to release specific molting hormones called ecdysteroids. After stimulation, likely by hormones, facial sutures start to break open. The “free cheeks”, or librigenae, are attached by facial sutures. The soft animal can slide out of the exoskeleton through the opening in those sutures.

Facial sutures terminate on the genal area of a trilobite's cephalic shield. (The spines that point laterally and outward from the cephalic shield are called genal spines!) The three kinds of sutures are defined by where the termination occurs: they are called proparian, gonatoparian, and opisthoparian. The proparian sutures terminate anterior to the genal angle; the opisthoparian sutures terminate on the posterior cephalic margin; and gonatoparian sutures terminate between the other two at the genal angle.

Suture position determined whether the visual surface stayed with the free cheeks or remained with the cranidium, and if need be new cornea material was reconstructed. Different species had different suture characteristics. Some groups such as Phacops and Asaphus had sutures which were inseparably fused: we can only speculate as to how they climbed out of their shells.

During exoskeleton reconditioning, trilobites may have secreted a thin prismatic layer first with a very thin primary layer underneath that continued to thicken. The primary layer resists cracking, making the exoskeleton strong enough to stand up to the force of preparation even after millions of years!

“Sheds” are the molted exoskeletons that prevail in the trilobite fossil record. They typically do not have free cheeks attached, but the cheeks are usually found near these quickly buried molts. It is believed that mating occurred post-molt while the animal was still soft.

Trilobite Eyes

Trilobites are the most primitive animals known to have vision. Some possessed stalked eyes, while others had turrets full of lenses, and some seem to have no eyes at all! Many trilobites evolved compound eyes with 360 degrees of vision.

Some trilobites have expansive lenses that are separately inlaid and lacking common corneas. This compound eye is an adaptive design of the suborder Phacopina. It is known as the schizochroal eye, and this style of sight is ideal for low-light conditions. This particular adaptation included up to 700 thick and relatively large lenses. The calcite that comprised the lens was extraordinarily pure. A system of mounted double lenses was effective for reducing the distortion that can occur with calcite crystals. Wide fields of view were an advantage to trilobites with perched or turreted eyes.

Some trilobites peered through the most ancient and widespread mode of trilobite vision-holochroal eyes. These eyes were often comprised of thousands of tiny lenses. A single corneal membrane covered all of the lenses of this compound eye. The lenses were packed closely in a hexagonal fashion. The eyes were not covered by the white layer of sclera: this absence is also seen in modern arthropods.

A few Cambrian species have the abathochroal eye. This type of vision is similar to the schizochroal eye. The sclera is not thick, and the corneal membrane does not reach downward like the intrascleral membrane, which deeply anchors the corneal membrane in holochroal and shizochroal eyes. In the abathochroal eye, the corneal membrane ends at the edge of the lens.

Trilobite Life Stages

Trilobites likely mated just after molting but before their exoskeletons hardened and thickened. After hatching from eggs, trilobites advanced through three different stages of distinctive morphology: protaspid, meraspid, and holaspid stages. Each successive stage included the addition of segments and ornamentation.

Adults in holaspid stage could continue to increase in size until their body masses and environmental limitations halted growth. While many trilobites are penny-sized to an inch or two long, several are quite small and others startlingly enormous: Isotelus rex could grow over two feet long!

Trilobite Extinction Events

The early Cambrian (521 MYA) marks trilobites' first appearance. Fossils from this era already display a high degree of diversity and geographic distribution, so emergence must have been much earlier. Trilobites continued to develop and radiate during the lower Paleozoic until their decline into the Devonian. Proetida is the only trilobite order that survived into the Permian. The Permian mass extinction that occurred 250 million years ago also took out the last trilobites.

The end of the Ordovician saw the onset of extensive ice ages. The consolidation of Pangea would have cooled the Earth by cutting off ocean currents. This affected populations in the open ocean, but trilobites living on warm continental shelves continued to thrive and diversify.

The evolution and proliferation of jawed fish likely exacerbated the decline of trilobites, but was probably not the primary reason for eventual extinction. They may have been reduced through warming and cooling trends caused by volcanism or the effects of a meteor impact. Very high carbon dioxide levels would have also killed marine species and affected the food chain. Overall, there is no definitive conclusion as to what eliminated these exotic treasures from the Earth.

Reviews

Reviews