How Large Did Mosasaurs Get?

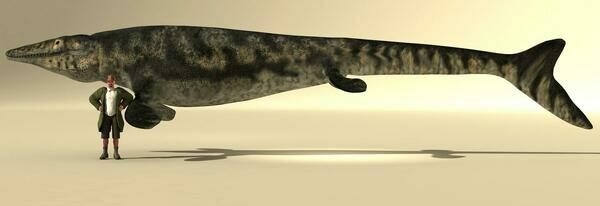

The mosasaurs were a group of swimming reptiles that originated in the Late Cretaceous period of the Mesozoic era roughly 95 million years ago, and would go on to become the dominant large marine predators of the era. Importantly, mosasaurs were not dinosaurs, they were an entirely different class of reptile, in the squamate group. Superseding the earlier ichthyosaurs and pliosaurs, these oceanic squamates related to snakes and monitor lizards were some of the largest marine organisms of the time, and some of the largest predatory reptiles, period. Mosasaurus hoffmanni, the largest known Mosasaur, averaged 39-42 feet long as adults and may have reached lengths up to 57 feet. Even the smallest of their number was about a meter, the same size as many small shark species. How did they get so large, and why?

Mosasaurs are descended from land dwelling reptiles, with some links to more primitive species like Aigialosaurus, which superficially resembled modern monitor lizards. They likely behaved similarly to marine iguanas, diving into the oceans to feed, and swimming mainly with lateral motion of the entire body. As they adapted further to the marine environment, they developed thicker bodies, their limbs flattened and became more paddle-like, and their tails developed flukes to aid in propulsion. In their early evolution they would have shared the seas with the short necked pliosaurids which they would ultimately come to replace ecologically.

Oceanic creatures are not nearly as limited in size by constraints such as gravity, as buoyancy cancels out much of the downward pressure and inward weight that growing so massive would cause on land. This can be seen today, as all the largest animals are sea-dwellers, and the largest animal of all time, the Blue Whale, is no exception. This lack of constraints is likely also the factor which allowed the mosasaurs and other marine reptiles to reach massive sizes. Mosasaurs also had double hinged, flexible jaws, much like snakes, which means they were not as constrained by the size of their prey as other, less-specialized animals.

The earliest mosasaurs were all smaller, with the smallest mosasaur of all, Dallasaurus, being only about 1m (3 ft.) in length, a far cry from the 14m (45 ft.) monsters that swam the seas much later. Dallasaurus was rather unique among mosasaurs for having a “plesiopedal” set of limbs, which is to say that it had distinct fingers and was presumably capable of walking on land. These in-between limbs allow paleontologists valuable insight on the transition from land to sea in the mosasaurs. Dallasaurus was also unique for being relatively primitive in body-type, but appearing during the late Cretaceous. It is the earliest known mosasaur from North America, dating back 92 million years.

Mosasaurs evolved larger sizes over the Cretaceous period, and were able to attain a worldwide distribution thanks to the rise in sea level, which is why today many mosasaur fossils can be found far inland, like in the American midwest.

While Dallasaurus was quite small for a mosasaur, it was uniquely primitive. Of the more typical mosasaurs, Platecarpus has a build more expected from the family. Despite being a “smaller” mosasaur, however, Platecarpus still reached nearly 5m (14ft) in length, rivaling many large marine predators both at the time and today. For comparison, Platecarpus reached about the same size as today’s Bottlenose Dolphin. Platecarpus likely fed in a similar manner, eating any fish or small animals it could fit into its mouth. It lived 84-81 million years ago.

Another mosasaur of similar size to Platecarpus was the more recent mosasaur Prognathodon. Known from 12 distinct species, the type species Prognathodon solvayi reached the same length as Platecarpus. The largest Prognathodon species, however, was P. currii, which reached double the length of P. solvayi, at 10m (32 ft). This is roughly the same size as the largest known Orca Whale, though Prognathodon likely hunted in a very different manner, ambushing prey in the open sea using countershaded patterning to stay hidden in the water column. It lived 83.6 million years ago, and lasted all the way until the end of the Mesozoic era, 66 million years ago. The smaller Prognathodon species likely also made for good sized prey for the larger mosasaurs.

Tylosaurus was one of the largest mosasaurs of all, reaching a length of about 13m (42 ft), with some estimations going even further, placing their maximum length at about 16m (52 ft). It was the apex predator of its environment, feeding on everything from diving birds, sharks, fish, ammonites, and even other mosasaurs. While certainly not as heavy, Tylosaurus would have reached the same length as many modern cetaceans, such as the Sperm Whale. The scales of Tylosaurus have been known from fossilized skin impressions since its discovery in the 1800s, revealing scales similar to both snakes and shark denticles. These scales would have reduced drag as the animal swam, making it a powerful ambush hunter. The largest known articulated mosasaur skeleton, a Tylosaurus skeleton nicknamed “Bruce”, reached a slightly longer length of 13.3m (43 ft) in length. Tylosaurus and Mosasaurus were only distantly related on the mosasaur family tree, with Tylosaurus being part of its own clade, the Tylosaurines. Tylosaurs had robust teeth and jaws, which suggests that they fed on larger prey. It lived 90 million years ago until the end of the Mesozoic.

As large as Tylosaurus got, Mosasaurus hoffmanni, the type species for Mosasaurus, was roughly the same size, possibly even larger. Average individuals are known to reach 12-13m (39-42 ft), while other evidence points to the existence of larger specimens. Mosasaurus’s size is still a topic of contention however, as the majority of well preserved material in the reptile comes from fossilized skulls, with much fewer remains known from the postcranial skeleton. Some estimates place the colossal mosasaurus as long as 17m (57 ft) in length, based on a lone skull bone determined to be 1.5x the size of the average known mosasaurus skull. Size estimates for an “average” mosasaurus of 13m (42ft) place its weight around 15 tons, while smaller specimens may have been only about 4 tons. If the estimates for larger individuals of 17m (57ft) hold true, then individuals of such a size could have exceeded 25 tons in weight. Mosasaurus was one of the last large mosasaurs, emerging about 82 million years ago and living until the end of the age of reptiles. Mosasaurus, Tylosaurus, and Prognathodon competed in several locations during the late Cretaceous, based on fossil injuries found on fossils in all three species. They seemingly were able to coexist over a long period of time in the environment, however, which suggests the three genera may have fed on different prey items.

These larger estimates, however, are based on conjectural analysis of very scant remains, and should be taken with a grain of salt. Paleontology is at times both precise and imprecise, and caution should be taken before definitive statements are made. Until more complete M. hoffmanni remains are found, the true limits of its stupendous size will remain just out of reach. It was however, undoubtedly a large animal, and among the largest reptilian predators the world has ever seen.

The last of the mosasaurs died out at the end of the Cretaceous period, 66 million years ago, when an enormous asteroid wiped out all the dominant reptilian clades of the Mesozoic era. Although they were great in size and number, they too could not escape extinction.

Grigoriev, D.W. (2014). "Giant Mosasaurus hoffmanni (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) of Penza, Russia" Proceedings of the Zoological Institute RAS. 318 (2): 148–167.

Wilf, P.; Reeder, T. W.; Townsend, T. M.; Mulcahy, D. G.; Noonan, B. P.; Wood, P. L.; Sites, J. W.; Wiens, J. J. (2015). "Integrated Analyses Resolve Conflicts over Squamate Reptile Phylogeny and Reveal Unexpected Placements for Fossil Taxa". PLOS ONE. 10 (3): e0118199.

Konishi, Takuya; Brinkman, Donald; Massare, Judy A.; Caldwell, Michael W. (2011-09-01). "New exceptional specimens of Prognathodon overtoni (Squamata, Mosasauridae) from the upper Campanian of Alberta, Canada, and the systematics and ecology of the genus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 31 (5): 1026–1046.

G. L. Bell, Jr.; Polcyn, M. J. (2005). "Dallasaurus turneri, a new primitive mosasauroid from the Middle Turonian of Texas and comments on the phylogeny of the Mosasauridae (Squamata)." Netherlands Journal of Geoscience (Geologie en Mijnbouw) 84 (3) pp. 177–194.

Kiernan CR, 2002. Stratigraphic distribution and habitat segregation of mosasaurs in the Upper Cretaceous of western and central Alabama, with an historical review of Alabama mosasaur discoveries. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22 (1): 91–103.

Everhart, Michael J.. Oceans of Kansas: A Natural History of the Western Interior Seaway. c. 2005.

Bullard, T.S.; Caldwell, M.W. (2010). "Redescription and rediagnosis of the tylosaurine mosasaur Hainosaurus pembinensis Nicholls, 1988, as Tylosaurus pembinensis (Nicholls, 1988)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 30 (2): 416–426.

Bruce - deep sea mosasaur - A Museum Called Manitoba

The Real Mosasaurus - Philip J. Currie Dinosaur Museum

On The Presence Of Prehistoric Pelagic Predators

Mosasaurs are descended from land dwelling reptiles, with some links to more primitive species like Aigialosaurus, which superficially resembled modern monitor lizards. They likely behaved similarly to marine iguanas, diving into the oceans to feed, and swimming mainly with lateral motion of the entire body. As they adapted further to the marine environment, they developed thicker bodies, their limbs flattened and became more paddle-like, and their tails developed flukes to aid in propulsion. In their early evolution they would have shared the seas with the short necked pliosaurids which they would ultimately come to replace ecologically.

Oceanic creatures are not nearly as limited in size by constraints such as gravity, as buoyancy cancels out much of the downward pressure and inward weight that growing so massive would cause on land. This can be seen today, as all the largest animals are sea-dwellers, and the largest animal of all time, the Blue Whale, is no exception. This lack of constraints is likely also the factor which allowed the mosasaurs and other marine reptiles to reach massive sizes. Mosasaurs also had double hinged, flexible jaws, much like snakes, which means they were not as constrained by the size of their prey as other, less-specialized animals.

Short and Long, Tall and Small

The earliest mosasaurs were all smaller, with the smallest mosasaur of all, Dallasaurus, being only about 1m (3 ft.) in length, a far cry from the 14m (45 ft.) monsters that swam the seas much later. Dallasaurus was rather unique among mosasaurs for having a “plesiopedal” set of limbs, which is to say that it had distinct fingers and was presumably capable of walking on land. These in-between limbs allow paleontologists valuable insight on the transition from land to sea in the mosasaurs. Dallasaurus was also unique for being relatively primitive in body-type, but appearing during the late Cretaceous. It is the earliest known mosasaur from North America, dating back 92 million years.

Mosasaurs evolved larger sizes over the Cretaceous period, and were able to attain a worldwide distribution thanks to the rise in sea level, which is why today many mosasaur fossils can be found far inland, like in the American midwest.

While Dallasaurus was quite small for a mosasaur, it was uniquely primitive. Of the more typical mosasaurs, Platecarpus has a build more expected from the family. Despite being a “smaller” mosasaur, however, Platecarpus still reached nearly 5m (14ft) in length, rivaling many large marine predators both at the time and today. For comparison, Platecarpus reached about the same size as today’s Bottlenose Dolphin. Platecarpus likely fed in a similar manner, eating any fish or small animals it could fit into its mouth. It lived 84-81 million years ago.

Another mosasaur of similar size to Platecarpus was the more recent mosasaur Prognathodon. Known from 12 distinct species, the type species Prognathodon solvayi reached the same length as Platecarpus. The largest Prognathodon species, however, was P. currii, which reached double the length of P. solvayi, at 10m (32 ft). This is roughly the same size as the largest known Orca Whale, though Prognathodon likely hunted in a very different manner, ambushing prey in the open sea using countershaded patterning to stay hidden in the water column. It lived 83.6 million years ago, and lasted all the way until the end of the Mesozoic era, 66 million years ago. The smaller Prognathodon species likely also made for good sized prey for the larger mosasaurs.

Tylosaurus was one of the largest mosasaurs of all, reaching a length of about 13m (42 ft), with some estimations going even further, placing their maximum length at about 16m (52 ft). It was the apex predator of its environment, feeding on everything from diving birds, sharks, fish, ammonites, and even other mosasaurs. While certainly not as heavy, Tylosaurus would have reached the same length as many modern cetaceans, such as the Sperm Whale. The scales of Tylosaurus have been known from fossilized skin impressions since its discovery in the 1800s, revealing scales similar to both snakes and shark denticles. These scales would have reduced drag as the animal swam, making it a powerful ambush hunter. The largest known articulated mosasaur skeleton, a Tylosaurus skeleton nicknamed “Bruce”, reached a slightly longer length of 13.3m (43 ft) in length. Tylosaurus and Mosasaurus were only distantly related on the mosasaur family tree, with Tylosaurus being part of its own clade, the Tylosaurines. Tylosaurs had robust teeth and jaws, which suggests that they fed on larger prey. It lived 90 million years ago until the end of the Mesozoic.

As large as Tylosaurus got, Mosasaurus hoffmanni, the type species for Mosasaurus, was roughly the same size, possibly even larger. Average individuals are known to reach 12-13m (39-42 ft), while other evidence points to the existence of larger specimens. Mosasaurus’s size is still a topic of contention however, as the majority of well preserved material in the reptile comes from fossilized skulls, with much fewer remains known from the postcranial skeleton. Some estimates place the colossal mosasaurus as long as 17m (57 ft) in length, based on a lone skull bone determined to be 1.5x the size of the average known mosasaurus skull. Size estimates for an “average” mosasaurus of 13m (42ft) place its weight around 15 tons, while smaller specimens may have been only about 4 tons. If the estimates for larger individuals of 17m (57ft) hold true, then individuals of such a size could have exceeded 25 tons in weight. Mosasaurus was one of the last large mosasaurs, emerging about 82 million years ago and living until the end of the age of reptiles. Mosasaurus, Tylosaurus, and Prognathodon competed in several locations during the late Cretaceous, based on fossil injuries found on fossils in all three species. They seemingly were able to coexist over a long period of time in the environment, however, which suggests the three genera may have fed on different prey items.

These larger estimates, however, are based on conjectural analysis of very scant remains, and should be taken with a grain of salt. Paleontology is at times both precise and imprecise, and caution should be taken before definitive statements are made. Until more complete M. hoffmanni remains are found, the true limits of its stupendous size will remain just out of reach. It was however, undoubtedly a large animal, and among the largest reptilian predators the world has ever seen.

The last of the mosasaurs died out at the end of the Cretaceous period, 66 million years ago, when an enormous asteroid wiped out all the dominant reptilian clades of the Mesozoic era. Although they were great in size and number, they too could not escape extinction.

Reviews

Reviews