Kem Kem Group History, Paleoecology, and Importance

Western North Africa has been studied extensively by geoscientists of all stripes since at least 1915, when German paleontologist Ernst Stromer broke ground and discovered a myriad of new fossil species in the region. The Kem Kem group specifically has been focused and studied as part of what geologists refer to as a “Continental Intercalaire” since the 1950’s. The name “continental intercalaire” refers to the layering of sedimentary rocks in the region, due to the mix of both continental and oceanic stone. This is also known as the "trilogie mésocrétacée" (mid-cretaceous trilogy), referring to the three distinct temporal layers of stone. The lower two layers are what paleontologist Paul Sereno informally referred to as “The Kem Kem beds” in the 1990’s, and the name has become synonymous with the Kem Kem group formation.

The Kem Kem group is best known from an escarpment of rock on the Morocco-Algerian border in Northern Africa, in what is now the Kem Kem region of modern day Morocco. The Kem Kem group layers date back to the Cenomanian age of the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 101-94 million years ago. The beds are home to extremely diverse and strange fauna from a unique part of Earth’s geological history, with famous dinosaur species like Spinosaurus and Carcharodontosaurus. There are also lesser known but equally impressive species such as Rebacchisaurus, a diplodocoid long-necked sauropod. In addition, many other non-dinosaur fossils have been found, indicating a wet and flooded delta habitat, with a range of fish, sharks, amphibians, turtles, squamates, crocodilians, and pterosaurs. The formation represents a window into a part of African prehistory when the continent was in contact with South America, and the Northern portion of Africa was mainly composed of massive river deltas in broad contact with the then-smaller Atlantic Ocean basin. This created a brackish and salty swampland that teemed with life. This is further evidenced by the uneven deposition of the layers of stone, with oceanic and continental rock being mixed together due to the tumultuous geological processes of erosion and deposition that occurred throughout the millennia.

In the modern day, the formation is a wealth of information for both new fossil finds, as well as for commercial fossil hunters. New discoveries come out of the region very frequently, and many interesting and bizarre revelations have come out about famous dinosaurs because of discoveries made there.

Quick Facts

“The Kem Kem beds” is an informal term coined by paleontologist Paul Sereno in a paper published in 1996. The term has become synonymous with the “Kem Kem group”, the actual name of the geological formation.

Many of the largest known theropod dinosaurs are known from material found in the Kem Kem group. These include Spinosaurus, possibly the largest theropod dinosaur at approximately 50 feet (15m), and Carcharodontosaurus, a large 40-foot (13m) predator, and one of the largest carcharodontosaurs.

Fragmentary remains indicate several other dinosaurs made their home in the area. These include evidence of long-necked titanosaur presence, with some scientists believing that the represented titanosaurs rivaled East African giants like Paralititan in size. If this were to be true, this would mean that the titanosaurs in question would be approximately 60-80 feet (20-27m) and 30-50 tons.

Several strange crocodilians are known from the area as well. Araripesuchus, also known by the informal name “RatCroc”, was a small crocodilian with a terrestrial lifestyle, with a smaller body and much longer legs than its modern relatives. Laganosuchus and Aegisuchus were crocodilians with flat, broad snouts that looked like paddles, adapted to swallow fish whole.

Pterosaurs are also well represented in the Kem Kem group. The most commonly represented genera are from the pterodactyloid family, with members such as Siroccopteryx, and Ornithocheirus, which was one of the largest toothed pterosaurs.

101 million years ago, during the Cenomanian age of the Late Cretaceous period, the Earth was a very different place. The continents of South America and Africa had hardly begun to break apart, and transfer of flora and fauna between the two was much greater than in the modern day. Because of the different arrangements of landmasses and ocean water, the global temperature was higher, and so was the sea level. Among the myriad effects of this, the area we know today as North Africa was not the desertified sahara of the modern day. Instead, it was a massive, lush system of river deltas, inletting from the diminishing Tethys Ocean and outletting into the slowly-expanding Atlantic.

A wet and warm habitat like the Kem Kem group would have been a veritable hotbed of evolutionary activity, spawning a wide variety of unique species and ecological niches. Massive predators, a diverse range of herbivores, bizarre crocodilians and more called the Kem Kem beds their home.

One of the most auspicious yet enigmatic members of the region was the gigantic Spinosaurus. At over 50 feet (15m), Spinosaurus aegypticus was possibly the largest theropod dinosaur that ever lived, but size is only one of the many interesting features of the so-called egyptian spine reptile. For nearly a century, little was known about the species, with only a detailed description of fragmentary remains to work off of. Recently, however, the Kem Kem group has recently shed some light on this mysterious creature. Its proportions were completely alien to most other theropods, with a long torso, short legs, a long, thick and flat tail structured much like a paddle, and a crocodile-like head. With this suite of adaptations it became evident to scientists that this unique theropod was probably quite suited to a semi-aquatic lifestyle. The high quantity of large fish in the region, coupled with the lack of similarly-sized crocodilian competitors would mean that Spinosaurus would have been the apex fish-eater in a wet and wild environment.

Carcharodontosaurus saharicus made waves after substantial remains were discovered in 1995 by a group led by paleontologist Paul Sereno. Carcharodontosaurus was a huge theropod dinosaur that reached over 40 feet (13m) in length, and nearly 6 tons, rivaling the famed Tyrannosaurus in size. Unlike Spinosaurus, Carcharodontosaurus was a fully terrestrial animal, and hunted prey in the Kem Kem region with its eponymous shark-like teeth. Likely targets include the sauropod Rebacchisaurus, as well as other mid to large-sized herbivores that lived in the region.

The related theropod Sauroniops pachytholus would also have lived in the region, however, due to the single fossil representing the species, some have argued that Sauroniops is synonymous with Carcharodontosaurus. The material comprising Sauroniops is represented by a single brow bone, which is where the genus gets its name (Sauroniops meaning “Eye of Sauron”, referring to the Lord of the Rings antagonist, also represented by a single large eye). Arguments against the genus refer to the scant remains, as well as the similarity of the material to the more well known and related Carcharodontosaurus. However paleontologist Andrea Cau, who named the species, points to distinct morphological discrepancies between the Sauroniops material and Carcharodontosaurus, specifically the length and size of contact points between the brow bone and the neighboring bones of the skull.

The smaller theropod Rugops primus would also have carved out its own niche in the territory. The 15-20 foot (5-6.5m) carnivore was a member of the short-faced theropod family known as “Abelisaurs’. Its presence in the area is quite enlightening. During the period that the Kem Kem group encompasses, the abelisaurs were smaller, and fed in the shadows of larger carnivores, like the Carcharodontosaurs. However, by the end of the Cretaceous, the carcharodontosaurs had gone extinct, and Abelisaurs were the dominant carnivores throughout the southern hemisphere. Rugops represents an earlier African radiation of abelisaurs, which originated at some point when South America and Africa were still a single continent, known as Gondwana. Its short face and relatively weak bite have made some scientists suggest a scavenging lifestyle.

Rebacchisaurus is one of the better known herbivorous representatives of the Kem Kem group. A sauropod diplodocoid dinosaur, Rebacchisaurus garasbae is known from partial remains, consisting of some high-spined back vertebrae, part of the pubic boot, and portions of the shoulder and front leg bones. The neural spines of Rebacchisaurus’ vertebrae were quite a bit taller than its relatives, though not as tall as spined dinosaurs like Spinosaurus or Ouranosaurus. In life, this would have manifested as a short sail along the animal’s back. Many people tend to think of large herbivorous dinosaurs like Rebacchisaurus as walking buffet tables for large theropods like Carcharodontosaurus, but they were far from defenseless. First of all, Rebacchisaurus was a huge animal. In 2010, Paul Sereno estimated Rebacchisaurus’ dimensions at around 46 feet (14m) in length and nearly 8 tons. More recent estimates have placed it at 65 feet (20m) and 86 feet (26m)/44 tons, respectively, though the debate is still open. Regardless, even at the smallest size estimates, Rebacchisaurus would have been larger than most contemporary predators, a major factor in deterring potential predators. Additionally, being a diplodocoid, Rebacchisaurus would have had a long tail with a slender, whiplike end section. Tests done on scale models of the tail of the related genus, Apatosaurus, show us that these tail whips could have potentially been able to break the sound barrier, as well as possibly deal tremendous damage to any potential predator.

Many other dinosaurs are known from more fragmentary, partial, or otherwise minimal remains. As stated previously, fragmentary, dispersed remains indicative of a large titanosaur, or possibly multiple titanosaurs, have been found in both layers of the Kem Kem group. These consist of some scattered teeth, neck vertebrae, and leg bones. Small teeth discovered in the region could possibly indicate the presence of a dromaeosaurid, more commonly known as a “raptor” type dinosaur. A footprint found in the region also suggests a hadrosaur of similar size to the European genus Iguanodon. Additionally, some scattered remains show evidence of another, non-rugops abelisaurid in the area.

Of course, dinosaurs are going to be the most obviously notable members of any mesozoic strata, but they weren’t the only ones who made their home in the swampy deltas of ancient Morocco. Pterosaurs, crocodilians, lizards, amphibians, fish, and a host of invertebrates lived all throughout the environment. And while none of these animals exceeded the largest dinosaurs of the area in size, they were quite fascinating in their own ways.

Pterosaurs are well represented in the Kem Kem group, from smaller species like Leptostomia, which is thought to have probed the sand with its thin beak like a modern day shorebird, to larger species like Ornithocheirus and Nicorhynchus, with wingspans of 20 feet (6m) and 23 feet (7m), respectively. There are no birds known from the Kem Kem group, so the pterosaurs of the area would have dominated the skies. The wet and deltaic habitat of the Cenomanian Kem Kem group would have been filled with all sorts of fish, lizards, amphibians, and invertebrates, which the carnivorous pterosaurs would have feasted on. The majority of pterosaurs in the Kem Kem group belonged to the pterodactyloid family, with some partial remains possibly indicating the presence of a large azhdarchoid. Larger pterosaurs like Ornithocheirus would have been skimmers, using their cone-toothed beaks to snatch fish near the surface of the water, while smaller species would have fed along the shore or further inland.

Crocodilians are another well represented group within the Kem Kem beds. Crocodilians before the K-Pg extinction were much more diverse than their modern counterparts, which are entirely semi-aquatic. Elosuchus represents a gharial-like genus, reaching about 15-20 feet (5-6m), its slender snout was built for snatching fish out of the water column. The previously mentioned Laganosuchus and Aegisuchus had long, flat snouts, with small teeth. These adaptations would have aided them as ambush predators, giving them a large area to snatch and swallow whole any animals that swam through their mouths. A much more sinister-seeming strategy for an animal whose name means “Pancake crocodile”, hm? On land, several crocodilians scavenged and filled roles of scavenger and low-level predators. Hamadasuchus and Antaeusuchus were blunt-toothed terrestrial crocodilians, which could suggest a more generalist diet. Araripesuchus, informally known as “RatCroc”, was a small (3ft/1m) sized omnivorous crocodilian, which used its lower jaw and a pair of projecting “buck” teeth to root through the ground for shrubs and grubs.

Tons of turtles, snakes, lizards and amphibians also lived and died within the Kem Kem region. Unnamed specimens belonging to the sirenid family of salamanders, as well as frogs in the pipidae family, the same as the modern dwarf clawed frog, have been found in the area. Representing the lizards, Bicuspidon was a species of polyglyphanodontid lizard, somewhat related to modern tegus. They were notable for having multiple different types of teeth, something fairly uncommon for most reptiles. The iguanid family is represented by Jeddaherden, a lizard known by a partial mandible containing characteristic teeth. Several primitive snakes can also be found there, as well as three genera of large turtles.

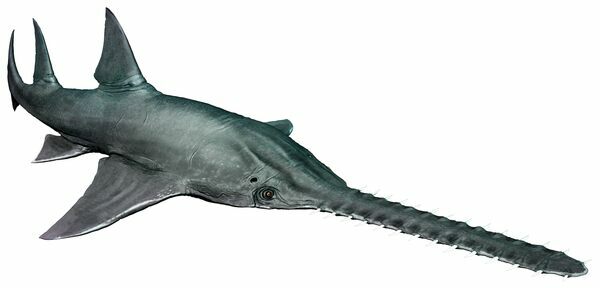

Being a large delta, fish are among the most prolific vertebrates found in the region. Arganodus and Neoceratodus africanus represent the lobe-finned fishes, along with the mawsoniid coelacanth, Axelrodichthys. Neoceratodus is a notable genus for having a living representative today, the queensland lungfish, Neoceratodus forsteri. Axelrodichthys is also interesting for showcasing how different cretaceous coelacanths were from their modern, fully marine relatives. Elasmobranchs, or cartilaginous fish, are well-represented in the Kem Kem region. Perhaps one of the most infamous is Onchopristis, a sawskate superficially quite similar to modern sawfish. Onchopristis was a large animal, approximately 28 feet (8m) in length, with a long nose lined with special barbed teeth, which it used to chop at prey and predators alike in the water column. Fossil remains of those barbs have been found with Spinosaurus remains, suggesting the dinosaur may have fed on the massive sawskate. Hybodonts, a group of sharks with conical teeth that are related but distinct from the modern shark family, are also common. A few scattered teeth are possibly representative of more modern shark lineages.

There are many ray-finned fishes that lived in the deltas as well. Diplomystus was a smaller, primitive fish from a group called otocephalians, the same group that contains modern herring and minnows. Bartschichthys, Bawitius, Serenoichthys, and Sudania all come from the same family as modern bichirs. Aidachar pankowski, a Moroccan representative of the genus Aidachar, was an ichthyodectiform fish, in the same family as the more well known Xiphactinus. This is just a short list of some of the more ubiquitous and notable fishes, and indeed, of life in the Moroccan deltas.

The Kem Kem beds are a wealth of fossil information, representing a large region of Northwestern Africa in a paleontological context. The unique deposition of marine and continental stone has provided an immense amount of geological and paleontological information. In a Cretaceous world where the ecosystem was changing steadily, the Kem Kem beds are a window into how life was adapting and evolving in the wake of major continental changes.

With the turonian, the Atlantic basin began expanding and sea level was lowering. The Moroccan deltas were beginning to shrink up, leaving many of the animals dependent on the riverine environment out to dry. Much of the upper sediment above the Kem Kem’s geological depth is eroded, leaving us to make inferences about the interregnum to follow.

In the modern day, we can keep observing and studying the material coming out of this one-of-a-kind site, furthering our understanding of paleontology.

Ibrahim N, Sereno PC, Varricchio DJ, Martill DM, Dutheil DB, Unwin DM, Baidder L, Larsson HCE, Zouhri S, Kaoukaya A (2020) Geology and paleontology of the Upper Cretaceous Kem Kem Group of eastern Morocco. ZooKeys 928: 1-216.

Theropoda: Sauroniops non è Carcharodontosaurus (Italian)

Dinosaur's Tail Whips Could Have Cracked Sound Barrier | Live Science

Mader, BJ & Kellner, Alexander W. A. (1999). "A new pterosaur from the Cretaceous of Morocco". Boletim do Museu Nacional (Rio de Janeiro), Geologia. Nova Série. 45: 1–11.

Larsson, H. C. E. and Sues, H.-D. (2007). Cranial osteology and phylogenetic relationships of Hamadasuchus rebouli (Crocodyliformes: Mesoeucrocodylia) from the Cretaceous of Morocco. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 149(4):533-567.

Cavin, Lionel & Boudad, Larbi & Tong, Haiyan & Läng, Emilie & Tabouelle, Jérôme & Vullo, Romain. (2015). Taxonomic Composition and Trophic Structure of the Continental Bony Fish Assemblage from the Early Late Cretaceous of Southeastern Morocco. PLoS ONE. 10. e0125786. 10.1371/journal.pone.0125786.

The Kem Kem group is best known from an escarpment of rock on the Morocco-Algerian border in Northern Africa, in what is now the Kem Kem region of modern day Morocco. The Kem Kem group layers date back to the Cenomanian age of the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 101-94 million years ago. The beds are home to extremely diverse and strange fauna from a unique part of Earth’s geological history, with famous dinosaur species like Spinosaurus and Carcharodontosaurus. There are also lesser known but equally impressive species such as Rebacchisaurus, a diplodocoid long-necked sauropod. In addition, many other non-dinosaur fossils have been found, indicating a wet and flooded delta habitat, with a range of fish, sharks, amphibians, turtles, squamates, crocodilians, and pterosaurs. The formation represents a window into a part of African prehistory when the continent was in contact with South America, and the Northern portion of Africa was mainly composed of massive river deltas in broad contact with the then-smaller Atlantic Ocean basin. This created a brackish and salty swampland that teemed with life. This is further evidenced by the uneven deposition of the layers of stone, with oceanic and continental rock being mixed together due to the tumultuous geological processes of erosion and deposition that occurred throughout the millennia.

In the modern day, the formation is a wealth of information for both new fossil finds, as well as for commercial fossil hunters. New discoveries come out of the region very frequently, and many interesting and bizarre revelations have come out about famous dinosaurs because of discoveries made there.

Quick Facts

Dinosaurs Of The Kem Kem Group

101 million years ago, during the Cenomanian age of the Late Cretaceous period, the Earth was a very different place. The continents of South America and Africa had hardly begun to break apart, and transfer of flora and fauna between the two was much greater than in the modern day. Because of the different arrangements of landmasses and ocean water, the global temperature was higher, and so was the sea level. Among the myriad effects of this, the area we know today as North Africa was not the desertified sahara of the modern day. Instead, it was a massive, lush system of river deltas, inletting from the diminishing Tethys Ocean and outletting into the slowly-expanding Atlantic.

A wet and warm habitat like the Kem Kem group would have been a veritable hotbed of evolutionary activity, spawning a wide variety of unique species and ecological niches. Massive predators, a diverse range of herbivores, bizarre crocodilians and more called the Kem Kem beds their home.

One of the most auspicious yet enigmatic members of the region was the gigantic Spinosaurus. At over 50 feet (15m), Spinosaurus aegypticus was possibly the largest theropod dinosaur that ever lived, but size is only one of the many interesting features of the so-called egyptian spine reptile. For nearly a century, little was known about the species, with only a detailed description of fragmentary remains to work off of. Recently, however, the Kem Kem group has recently shed some light on this mysterious creature. Its proportions were completely alien to most other theropods, with a long torso, short legs, a long, thick and flat tail structured much like a paddle, and a crocodile-like head. With this suite of adaptations it became evident to scientists that this unique theropod was probably quite suited to a semi-aquatic lifestyle. The high quantity of large fish in the region, coupled with the lack of similarly-sized crocodilian competitors would mean that Spinosaurus would have been the apex fish-eater in a wet and wild environment.

Carcharodontosaurus saharicus made waves after substantial remains were discovered in 1995 by a group led by paleontologist Paul Sereno. Carcharodontosaurus was a huge theropod dinosaur that reached over 40 feet (13m) in length, and nearly 6 tons, rivaling the famed Tyrannosaurus in size. Unlike Spinosaurus, Carcharodontosaurus was a fully terrestrial animal, and hunted prey in the Kem Kem region with its eponymous shark-like teeth. Likely targets include the sauropod Rebacchisaurus, as well as other mid to large-sized herbivores that lived in the region.

The related theropod Sauroniops pachytholus would also have lived in the region, however, due to the single fossil representing the species, some have argued that Sauroniops is synonymous with Carcharodontosaurus. The material comprising Sauroniops is represented by a single brow bone, which is where the genus gets its name (Sauroniops meaning “Eye of Sauron”, referring to the Lord of the Rings antagonist, also represented by a single large eye). Arguments against the genus refer to the scant remains, as well as the similarity of the material to the more well known and related Carcharodontosaurus. However paleontologist Andrea Cau, who named the species, points to distinct morphological discrepancies between the Sauroniops material and Carcharodontosaurus, specifically the length and size of contact points between the brow bone and the neighboring bones of the skull.

The smaller theropod Rugops primus would also have carved out its own niche in the territory. The 15-20 foot (5-6.5m) carnivore was a member of the short-faced theropod family known as “Abelisaurs’. Its presence in the area is quite enlightening. During the period that the Kem Kem group encompasses, the abelisaurs were smaller, and fed in the shadows of larger carnivores, like the Carcharodontosaurs. However, by the end of the Cretaceous, the carcharodontosaurs had gone extinct, and Abelisaurs were the dominant carnivores throughout the southern hemisphere. Rugops represents an earlier African radiation of abelisaurs, which originated at some point when South America and Africa were still a single continent, known as Gondwana. Its short face and relatively weak bite have made some scientists suggest a scavenging lifestyle.

Rebacchisaurus is one of the better known herbivorous representatives of the Kem Kem group. A sauropod diplodocoid dinosaur, Rebacchisaurus garasbae is known from partial remains, consisting of some high-spined back vertebrae, part of the pubic boot, and portions of the shoulder and front leg bones. The neural spines of Rebacchisaurus’ vertebrae were quite a bit taller than its relatives, though not as tall as spined dinosaurs like Spinosaurus or Ouranosaurus. In life, this would have manifested as a short sail along the animal’s back. Many people tend to think of large herbivorous dinosaurs like Rebacchisaurus as walking buffet tables for large theropods like Carcharodontosaurus, but they were far from defenseless. First of all, Rebacchisaurus was a huge animal. In 2010, Paul Sereno estimated Rebacchisaurus’ dimensions at around 46 feet (14m) in length and nearly 8 tons. More recent estimates have placed it at 65 feet (20m) and 86 feet (26m)/44 tons, respectively, though the debate is still open. Regardless, even at the smallest size estimates, Rebacchisaurus would have been larger than most contemporary predators, a major factor in deterring potential predators. Additionally, being a diplodocoid, Rebacchisaurus would have had a long tail with a slender, whiplike end section. Tests done on scale models of the tail of the related genus, Apatosaurus, show us that these tail whips could have potentially been able to break the sound barrier, as well as possibly deal tremendous damage to any potential predator.

Many other dinosaurs are known from more fragmentary, partial, or otherwise minimal remains. As stated previously, fragmentary, dispersed remains indicative of a large titanosaur, or possibly multiple titanosaurs, have been found in both layers of the Kem Kem group. These consist of some scattered teeth, neck vertebrae, and leg bones. Small teeth discovered in the region could possibly indicate the presence of a dromaeosaurid, more commonly known as a “raptor” type dinosaur. A footprint found in the region also suggests a hadrosaur of similar size to the European genus Iguanodon. Additionally, some scattered remains show evidence of another, non-rugops abelisaurid in the area.

Flying, Fishing, Fleeing And Floating: Assorted Non-Dinosaurian Fauna Of The Kem Kem Group

Of course, dinosaurs are going to be the most obviously notable members of any mesozoic strata, but they weren’t the only ones who made their home in the swampy deltas of ancient Morocco. Pterosaurs, crocodilians, lizards, amphibians, fish, and a host of invertebrates lived all throughout the environment. And while none of these animals exceeded the largest dinosaurs of the area in size, they were quite fascinating in their own ways.

Pterosaurs are well represented in the Kem Kem group, from smaller species like Leptostomia, which is thought to have probed the sand with its thin beak like a modern day shorebird, to larger species like Ornithocheirus and Nicorhynchus, with wingspans of 20 feet (6m) and 23 feet (7m), respectively. There are no birds known from the Kem Kem group, so the pterosaurs of the area would have dominated the skies. The wet and deltaic habitat of the Cenomanian Kem Kem group would have been filled with all sorts of fish, lizards, amphibians, and invertebrates, which the carnivorous pterosaurs would have feasted on. The majority of pterosaurs in the Kem Kem group belonged to the pterodactyloid family, with some partial remains possibly indicating the presence of a large azhdarchoid. Larger pterosaurs like Ornithocheirus would have been skimmers, using their cone-toothed beaks to snatch fish near the surface of the water, while smaller species would have fed along the shore or further inland.

Crocodilians are another well represented group within the Kem Kem beds. Crocodilians before the K-Pg extinction were much more diverse than their modern counterparts, which are entirely semi-aquatic. Elosuchus represents a gharial-like genus, reaching about 15-20 feet (5-6m), its slender snout was built for snatching fish out of the water column. The previously mentioned Laganosuchus and Aegisuchus had long, flat snouts, with small teeth. These adaptations would have aided them as ambush predators, giving them a large area to snatch and swallow whole any animals that swam through their mouths. A much more sinister-seeming strategy for an animal whose name means “Pancake crocodile”, hm? On land, several crocodilians scavenged and filled roles of scavenger and low-level predators. Hamadasuchus and Antaeusuchus were blunt-toothed terrestrial crocodilians, which could suggest a more generalist diet. Araripesuchus, informally known as “RatCroc”, was a small (3ft/1m) sized omnivorous crocodilian, which used its lower jaw and a pair of projecting “buck” teeth to root through the ground for shrubs and grubs.

Tons of turtles, snakes, lizards and amphibians also lived and died within the Kem Kem region. Unnamed specimens belonging to the sirenid family of salamanders, as well as frogs in the pipidae family, the same as the modern dwarf clawed frog, have been found in the area. Representing the lizards, Bicuspidon was a species of polyglyphanodontid lizard, somewhat related to modern tegus. They were notable for having multiple different types of teeth, something fairly uncommon for most reptiles. The iguanid family is represented by Jeddaherden, a lizard known by a partial mandible containing characteristic teeth. Several primitive snakes can also be found there, as well as three genera of large turtles.

Being a large delta, fish are among the most prolific vertebrates found in the region. Arganodus and Neoceratodus africanus represent the lobe-finned fishes, along with the mawsoniid coelacanth, Axelrodichthys. Neoceratodus is a notable genus for having a living representative today, the queensland lungfish, Neoceratodus forsteri. Axelrodichthys is also interesting for showcasing how different cretaceous coelacanths were from their modern, fully marine relatives. Elasmobranchs, or cartilaginous fish, are well-represented in the Kem Kem region. Perhaps one of the most infamous is Onchopristis, a sawskate superficially quite similar to modern sawfish. Onchopristis was a large animal, approximately 28 feet (8m) in length, with a long nose lined with special barbed teeth, which it used to chop at prey and predators alike in the water column. Fossil remains of those barbs have been found with Spinosaurus remains, suggesting the dinosaur may have fed on the massive sawskate. Hybodonts, a group of sharks with conical teeth that are related but distinct from the modern shark family, are also common. A few scattered teeth are possibly representative of more modern shark lineages.

There are many ray-finned fishes that lived in the deltas as well. Diplomystus was a smaller, primitive fish from a group called otocephalians, the same group that contains modern herring and minnows. Bartschichthys, Bawitius, Serenoichthys, and Sudania all come from the same family as modern bichirs. Aidachar pankowski, a Moroccan representative of the genus Aidachar, was an ichthyodectiform fish, in the same family as the more well known Xiphactinus. This is just a short list of some of the more ubiquitous and notable fishes, and indeed, of life in the Moroccan deltas.

The Turonian: End Of The Kem Kem Calendar

The Kem Kem beds are a wealth of fossil information, representing a large region of Northwestern Africa in a paleontological context. The unique deposition of marine and continental stone has provided an immense amount of geological and paleontological information. In a Cretaceous world where the ecosystem was changing steadily, the Kem Kem beds are a window into how life was adapting and evolving in the wake of major continental changes.

With the turonian, the Atlantic basin began expanding and sea level was lowering. The Moroccan deltas were beginning to shrink up, leaving many of the animals dependent on the riverine environment out to dry. Much of the upper sediment above the Kem Kem’s geological depth is eroded, leaving us to make inferences about the interregnum to follow.

In the modern day, we can keep observing and studying the material coming out of this one-of-a-kind site, furthering our understanding of paleontology.

References

Theropoda: Sauroniops non è Carcharodontosaurus (Italian)

Reviews

Reviews