Spinosaurus: The Sail-Backed River Hunter

The story of Spinosaurus begins not with a thunderous roar on open plains, but with ripples spreading across the surface of an ancient river system nearly 95 million years ago, during the mid-Cretaceous Period. This was a predator built for water as much as land, one that challenges nearly every stereotype of what a dinosaur was supposed to be. Longer than any other known carnivorous dinosaur, taller than a giraffe when its sail is fully raised, and armed with a skull more like a crocodile’s than a tyrant’s, Spinosaurus remains one of the most extraordinary animals ever discovered in the fossil record.

Unlike most large theropods, Spinosaurus was not designed for bone-crushing bites or high-speed pursuit. Its jaws were long and narrow, packed with smooth, conical teeth ideal for gripping slippery prey. Its nostrils sat far back on the skull, allowing it to breathe while much of its snout was submerged. Its bones were unusually dense—more like those of penguins or hippos than typical dinosaurs—helping counteract buoyancy in water. Even its massive tail, once thought to be ordinary, is now known to have been tall and laterally compressed, forming a powerful swimming organ unlike anything seen in other non-avian dinosaurs.

Perhaps most iconic of all was the enormous sail that rose from its back, formed by elongated neural spines that could exceed five feet in height. Whether used for display, thermoregulation, species recognition, or some combination of functions, the sail ensured that Spinosaurus would have been an unmistakable presence along the waterways of Cretaceous Africa.

What makes Spinosaurus especially compelling is not just how strange it was, but how often it has forced scientists to rethink their assumptions. Few dinosaurs have been reconstructed so many times—or so differently. Over the past century, Spinosaurus has transformed from a vaguely known sail-backed curiosity into the centerpiece of one of paleontology’s most intense debates: could a dinosaur truly live and hunt in the water?

Once a footnote known from fragments and wartime photographs, Spinosaurus is now a symbol of scientific revision. Each new discovery—from shortened hind limbs to swimming-adapted tails—has added complexity rather than clarity. More than any other dinosaur, Spinosaurus stands as a reminder that the prehistoric world was far stranger, more experimental, and more diverse than our imaginations once allowed.

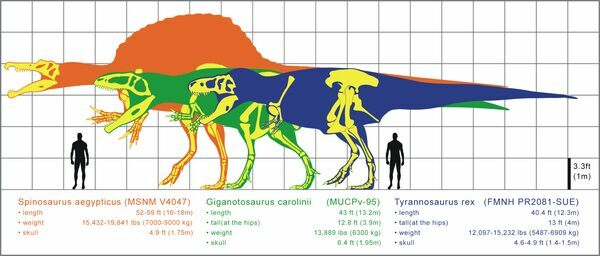

Spinosaurus is currently regarded as the longest known carnivorous dinosaur, with length estimates ranging from about 14 to over 15 meters (46–50+ feet), and possibly more depending on reconstruction. In sheer linear size, it exceeded even Tyrannosaurus rex, though it was built very differently. Weight estimates are more uncertain due to its unusual proportions, but most recent studies suggest Spinosaurus weighed roughly 6 to 9 metric tons—comparable to, or slightly lighter than, the largest T. rex specimens despite being significantly longer. Its elongated body, neck, and tail gave it a low, stretched silhouette unlike any other theropod, emphasizing length over bulk.

One of the most striking features of Spinosaurus was the enormous sail that rose from its back, formed by elongated neural spines extending from the vertebrae. In some individuals, these spines exceeded five feet in height, meaning the sail alone could rival the height of an adult human. Combined with its overall body size, this would have made Spinosaurus one of the tallest dinosaurs when viewed in profile. The function of the sail has been widely debated, with hypotheses ranging from visual display and species recognition to thermoregulation or even structural support for a low, fleshy hump. It is likely that the sail served multiple roles, shifting in importance depending on behavior, age, or environment.

The skull of Spinosaurus was long, narrow, and low, reaching lengths of over 1.6 meters (more than five feet) in some estimates—longer than the skull of T. rex. Its jaws were lined with smooth, conical teeth lacking serrations, ideal for gripping fish rather than tearing flesh. The snout was reinforced at the front, and the nostrils were positioned far back on the skull—an adaptation that allowed the animal to breathe while much of its snout was submerged in water.

The rest of the skeleton was just as unusual. Spinosaurus possessed unusually dense bones, a condition known as pachyostosis, which reduced buoyancy and helped stabilize the animal in water. Its hind limbs were short relative to body size, especially for an animal of such length, suggesting limited efficiency in fast terrestrial locomotion. In contrast, the tail was long, deep, and laterally compressed, forming a powerful swimming organ capable of generating propulsion in water.

Taken together, these traits—extreme length, massive but lightly built frame, towering sail, specialized skull, dense bones, reduced legs, and swimming tail—mark Spinosaurus as one of the most anatomically specialized dinosaurs ever discovered. Rather than excelling at speed or brute force, it was built for control, stability, and dominance in river-dominated environments.

Spinosaurus was first described in 1915 by German paleontologist Ernst Stromer von Reichenbach, based on fossils recovered from the Bahariya Formation of Egypt. These remains included parts of the skull, vertebrae, ribs, and pelvis—enough to establish a truly bizarre new theropod. Stromer named it Spinosaurus, meaning “Egyptian spine lizard.”

Tragically, the original fossils were housed in Munich and destroyed during an Allied bombing raid in 1944. For decades afterward, Spinosaurus existed only in Stromer’s detailed notes, photographs, and illustrations. This loss turned Spinosaurus into something of a ghost—famous, intriguing, but frustratingly incomplete.

The fossil record of Spinosaurus is one of the most challenging and controversial of any famous dinosaur. Unlike animals known from complete or near-complete skeletons, Spinosaurus is reconstructed from a patchwork of fossils collected over more than a century, from multiple countries, formations, and geological contexts. No single individual preserves the full skeleton, and many bones attributed to Spinosaurus have never been found in direct association with one another.

This fragmentary record is not merely inconvenient—it is central to why Spinosaurus has been so frequently reinterpreted. Each new discovery has the potential to dramatically alter reconstructions, because entire regions of the skeleton remain poorly known or entirely absent from the fossil record.

The original fossils described by Ernst Stromer from Egypt’s Bahariya Formation formed the foundation of everything known about Spinosaurus for decades. These remains included portions of the skull, distinctive sail-bearing vertebrae, ribs, gastralia, and elements of the pelvis. Stromer’s careful descriptions and photographs revealed a theropod unlike any other, but even this original material was incomplete.

The destruction of the holotype during World War II created a unique scientific problem. Because the original bones no longer exist, modern researchers must rely on Stromer’s records to interpret new material. This has complicated efforts to confirm whether later discoveries perfectly match the original animal or represent variation within a broader spinosaurid group.

Throughout the mid-to-late 20th century, isolated teeth and bones attributed to Spinosaurus were recovered across North Africa, particularly in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Egypt. Many of these fossils came from river-deposited sediments, consistent with an aquatic or semi-aquatic lifestyle. However, isolated spinosaurid teeth are notoriously difficult to assign to genus or species, leading to debates over misidentification and over-attribution.

Some material historically labeled as Spinosaurus has since been reassigned to other spinosaurids or deemed indeterminate. This has fueled skepticism, with some researchers questioning whether Spinosaurus was being reconstructed from a mixture of multiple related animals rather than a single coherent form.

The most significant expansion of the Spinosaurus fossil record has come from the Kem Kem Beds of southeastern Morocco. Here, numerous skeletal elements—including vertebrae, limb bones, and parts of the tail—have been recovered from Cenomanian-aged deposits. While often found disarticulated, these fossils provide crucial insights into body proportions and adaptations.

In particular, discoveries of shortened hind limbs and an unusually tall, laterally compressed tail revolutionized interpretations of Spinosaurus anatomy. These finds suggested an animal with limited terrestrial locomotion but enhanced swimming ability, reinforcing the idea that Spinosaurus occupied a unique ecological niche among dinosaurs.

Modern reconstructions of Spinosaurus are necessarily composite, drawing from multiple individuals and localities. This approach is not unique in paleontology, but it carries special risks when applied to an animal as unusual as Spinosaurus. Small errors or misassignments can have outsized effects on interpretations of posture, locomotion, and lifestyle.

As a result, Spinosaurus remains one of the most fluid dinosaurs in scientific visualization. New fossils continue to refine—and sometimes overturn—previous assumptions. Rather than a weakness, this ongoing revision highlights the dynamic nature of paleontology, where even the most famous dinosaurs can still be fundamentally redefined by a single bone.

Understanding Spinosaurus requires understanding the world it lived in. Much of what we know about its anatomy, behavior, and ecological role comes not just from its bones, but from the environment preserved around them. For this reason, the Kem Kem Beds of southeastern Morocco are central to any discussion of Spinosaurus—they represent the richest source of fossils attributed to this animal and provide critical context for interpreting how it lived.

The Kem Kem Beds date to the Cenomanian stage of the Late Cretaceous, approximately 95 million years ago. At the time, this region was not the arid desert seen today, but a vast, low-lying river system draining into the Tethys Sea. Broad rivers, seasonal floodplains, wetlands, and coastal lagoons dominated the landscape, creating an ecosystem exceptionally rich in aquatic life.

This environment supported one of the most predator-heavy ecosystems ever discovered in the fossil record. Enormous fish, including sawfish and giant coelacanths, were abundant. Massive crocodyliforms such as Sarcosuchus patrolled the waterways, while turtles and lungfish thrived in quieter channels. Pterosaurs soared overhead, and multiple species of large theropod dinosaurs stalked the floodplains.

Among these predators were Carcharodontosaurus, a land-dominating giant adapted for hunting large dinosaurs, and Deltadromeus, a long-legged, lightly built theropod likely specialized for speed. The coexistence of so many large carnivores suggests strong ecological partitioning, with each predator exploiting a different food source or habitat.

Within this crowded and dangerous ecosystem, Spinosaurus appears to have occupied a unique role. Its anatomy is ideally suited for exploiting aquatic prey that other theropods could not efficiently access. By hunting primarily in rivers and wetlands, Spinosaurus may have reduced direct competition with terrestrial predators while taking advantage of an abundant and renewable food source.

The Kem Kem Beds also help explain why Spinosaurus evolved such extreme specializations. A river system rich in large fish would favor predators capable of swimming, wading, and maintaining stability in water. Over time, these pressures likely shaped the unusual body plan seen in Spinosaurus, reinforcing its status as a river-dwelling specialist rather than a generalist land predator.

Because many Spinosaurus fossils come from disarticulated river deposits, the Kem Kem Beds also illustrate the challenges of reconstructing the animal. Bones transported by water are often scattered and mixed with remains of other animals, complicating efforts to associate skeletal elements. Nevertheless, the sheer volume of material from this region has made it indispensable to modern reconstructions of Spinosaurus.

To understand Spinosaurus, one must picture it not charging across open ground, but standing motionless in a river channel, water lapping against its flanks, jaws poised just above the surface. Feeding was not simply one aspect of its biology—it was the organizing principle around which its entire body was built.

Unlike most giant theropods, whose skulls were optimized for tearing flesh and crushing bone, Spinosaurus evolved into a specialist hunter of aquatic prey. Its long, narrow snout cut cleanly through water, reducing resistance and allowing rapid, precise strikes. This was a predator shaped by patience and positioning rather than raw power.

Its jaws were lined with smooth, conical teeth—dozens of them—lacking the sharp serrations seen in meat-slicing dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus. These teeth functioned less like knives and more like spikes, ideal for gripping slippery, struggling fish. Once clamped shut, escape would have been nearly impossible. The reinforced tip of the snout helped absorb twisting forces as prey thrashed, much like the jaws of modern crocodilians and gharials.

One remarkable consequence of this feeding strategy is how common Spinosaurus teeth are in the fossil record. Like crocodiles today, Spinosaurus continuously shed and replaced its teeth throughout its life. Teeth lost during feeding—snapped off, loosened, or naturally replaced—would sink into river sediments, where they fossilized in enormous numbers. This constant tooth replacement explains why isolated Spinosaurus teeth are among the most frequently found dinosaur fossils in North Africa, even when bones are rare.

These teeth, often beautifully preserved, offer critical insight into the animal’s diet and behavior. Their rounded cross-sections, enamel texture, and lack of wear from bone-crushing all reinforce the picture of a predator feeding primarily on fish rather than large terrestrial animals.

Evidence from close relatives strengthens this interpretation. Fossils of Baryonyx preserve fish scales within the ribcage, while spinosaurid bite marks have been found on fossil fish bones. Given the near-identical skull and tooth design, there is little doubt that fish formed the backbone of Spinosaurus’ diet.

Feeding likely involved a mix of wading and slow swimming. Dense limb bones helped stabilize the body in water, preventing excessive buoyancy, while the tall, laterally compressed tail provided fine control and propulsion. With its nostrils positioned far back on the skull, Spinosaurus could breathe while much of its snout remained submerged—an ideal setup for ambush hunting in murky rivers.

Although fish were its primary target, Spinosaurus was almost certainly opportunistic. Small to medium-sized dinosaurs, turtles, pterosaurs near the water’s edge, and carrion would not have been ignored. Like modern crocodiles, it likely took advantage of easy meals rather than engaging in risky confrontations. Its jaw mechanics suggest it was poorly suited for prolonged struggles with large, heavily built prey, favoring quick strikes and minimal resistance instead.

In the predator-rich ecosystems of the Kem Kem Beds, this feeding strategy was key to survival. By specializing in aquatic prey, Spinosaurus avoided direct competition with massive land predators such as Carcharodontosaurus. The rivers provided a renewable, protein-rich food source that few other dinosaurs could exploit efficiently.

In this way, the diet of Spinosaurus was far more than a curiosity. It was the foundation of its anatomy, its behavior, and its success—a river predator perfectly tuned to a world of flowing water, shifting channels, and endless schools of fish.

Few dinosaurs have stirred as much scientific argument as Spinosaurus, and at the heart of that debate lies a deceptively simple question: how much time did it actually spend in the water?

For much of the 20th century, the answer seemed obvious—dinosaurs, by definition, were land animals. Early paleontologists worked within that assumption, and Spinosaurus was no exception. Despite its crocodile-like skull and fish-eating teeth, it was typically reconstructed as a shoreline predator: a dinosaur that hunted fish along riverbanks but lived, walked, and moved much like other giant theropods.

That picture began to erode as new fossils filled in the blanks left by the destroyed original material. Shortened hind limbs emerged from the rock, raising immediate questions about how efficiently Spinosaurus could move on land. Studies of its bones revealed something even more surprising—they were unusually dense, heavier than those of most dinosaurs, a trait shared by many animals that spend much of their lives in water. Chemical signatures locked within its teeth told the same story. By analyzing stable oxygen isotopes preserved in Spinosaurus tooth enamel, researchers were able to compare its chemical profile with those of animals living in the same ecosystem. The results showed that Spinosaurus clustered closely with aquatic and semi-aquatic animals—such as crocodilians and large fish—rather than with land-dwelling theropods. Because tooth enamel forms slowly and records the chemistry of an animal’s drinking water and prey over time, these isotopic signatures suggest that Spinosaurus spent a significant portion of its life in aquatic environments, not merely visiting rivers occasionally but living within them as a regular part of its ecology.

The debate reached a turning point with the discovery of Spinosaurus tail vertebrae unlike anything previously known in a theropod. Tall neural spines and elongated chevrons formed a deep, laterally compressed tail capable of pushing against water. For some researchers, this was the missing piece of the puzzle—a dinosaur not merely associated with water, but one capable of swimming.

The idea of a truly aquatic dinosaur, however, was bound to invite skepticism. Critics argued that adaptation does not imply exclusivity. Dense bones and a swimming-capable tail, they noted, do not automatically make an animal a pursuit swimmer. Comparisons were drawn to hippos and other semi-aquatic mammals that spend hours submerged yet remain dependent on land.

Retracted nostrils positioned high on the skull

Unlike most theropods, Spinosaurus had small nostrils placed far back on its snout — an advantage when breathing while much of its head was submerged in water.

Pressure-sensing neurovascular openings - Tiny neurovascular canals at the tip of the snout resemble those in modern crocodilians, where they house receptors that detect water movement. This may have helped Spinosaurus sense nearby fish.

Interlocking conical teeth - Its giant, slanted, conical teeth — ideal for gripping fish — would have worked like built-in fishhooks.

Long neck and trunk shifting body balance forward - A stretched neck and torso moved the center of mass ahead of the hips — great for hunting in water, less ideal for sustained land locomotion.

Robust forelimbs with curved claws - These powerful arms, with blade-like claws, may have helped Spinosaurus hook or slice slippery prey out of water.

Small pelvis and shortened hind limbs - The pelvic girdle was reduced and the hind legs were comparatively short — traits convergent with early whales and other animals that adapted from land into water.

Dense limb bones - Unlike most theropods with hollow bones, Spinosaurus had osteosclerotic bones (solid and heavy) that helped counteract buoyancy — just as seen in penguins and other aquatic animals.

Feet built for mud and shallow water - The bones of its feet were long and flat, similar to shorebirds that traverse soft ground. Some researchers propose Spinosaurus may even have had webbing, helping it walk on muddy banks or paddle.

Flexible, wave-like tail anatomy - A tail with loosely connected bones could bend in a wave-like fashion, similar to how fish and other swimming animals generate thrust.

Today, the debate has shifted away from absolutes. Rather than asking whether Spinosaurus was aquatic or terrestrial, most paleontologists now ask how aquatic it was. On that spectrum, Spinosaurus sits at the far extreme—more water-adapted than any other known non-avian dinosaur, even if it never fully abandoned the land. The controversy, far from being settled, continues to refine our understanding of how flexible and experimental dinosaur lifestyles could truly be.

The classification of Spinosaurus is one of the most debated topics surrounding the genus, reflecting both its fragmentary fossil record and the complex history of spinosaurid discoveries in Africa and beyond. While Spinosaurus is universally recognized as a member of the family Spinosauridae, its internal taxonomy—how many species it contains and which fossils truly belong to it—remains unresolved.

Spinosauridae is a distinctive group of theropod dinosaurs characterized by elongated, crocodile-like skulls, conical teeth, and a strong association with aquatic environments. Within this family, Spinosaurus is generally considered part of the subfamily Spinosaurinae, alongside close relatives such as Irritator and Oxalaia. Members of this subgroup tend to have longer, narrower snouts and more pronounced aquatic adaptations than baryonychines such as Baryonyx.

Within Spinosaurinae, Spinosaurus stands apart due to its immense size, extreme skeletal specializations, and iconic dorsal sail, making it the most derived and unusual member of the group.

The genus Spinosaurus was established on the basis of the Egyptian material described by Ernst Stromer in 1915. This material defines the type species, Spinosaurus aegyptiacus. Because the original fossils were destroyed during World War II, modern researchers must rely on Stromer’s descriptions and illustrations to evaluate whether newly discovered material truly belongs to the same species.

This loss has had lasting consequences. Without the ability to directly compare new fossils to the original bones, it is difficult to determine whether anatomical differences represent variation within a single species or evidence of multiple species within the genus.

Over the years, several additional species names have been proposed based on fragmentary material, most notably Spinosaurus maroccanus, named from isolated vertebrae discovered in Morocco. Many paleontologists consider this species dubious, arguing that the material lacks unique diagnostic features and may instead represent individual variation or belong to another spinosaurid entirely.

Other North African fossils have sometimes been attributed to Spinosaurus without being assigned to a specific species, further blurring taxonomic boundaries. Differences in vertebrae proportions, limb elements, and size have fueled speculation that more than one species of Spinosaurus may have existed across Africa during the Late Cretaceous.

The Brazilian genus Oxalaia has occasionally been suggested as a potential southern representative of Spinosaurus, based primarily on similarities in skull material. However, the remains of Oxalaia are extremely fragmentary, and most researchers currently prefer to keep it separate until more complete fossils are discovered.

This debate highlights a broader issue in spinosaurid classification: many fossils are known from isolated bones or teeth, which are difficult to assign confidently at the genus or species level. As a result, some material attributed to Spinosaurus may eventually be reassigned, while other fossils currently considered indeterminate could later expand the genus.

At present, most paleontologists adopt a conservative approach, recognizing Spinosaurus as a valid genus likely represented by a single well-established species, while acknowledging the possibility that future discoveries could reveal greater diversity. Until more complete, articulated skeletons are found, the internal classification of Spinosaurus will remain provisional.

This taxonomic uncertainty is not a weakness, but a reflection of how paleontology works at the frontier of discovery. As new fossils emerge, the classification of Spinosaurus—like its anatomy and lifestyle—may yet be rewritten.

Spinosaurus belonged to the family Spinosauridae, a distinctive lineage of theropod dinosaurs that diverged early from other large carnivorous dinosaurs. While most giant theropods evolved toward powerful bites and fully terrestrial hunting strategies, spinosaurids followed a different evolutionary path—one increasingly shaped by life along rivers, lakes, and coastal environments.

The earliest known spinosaurids appear in the Early Cretaceous, with fossils found in Europe suggesting that the group may have originated there. Early members such as Baryonyx display a mix of traits: long, narrow jaws and conical teeth adapted for fish-eating, paired with relatively long hind limbs and proportions still well suited for walking on land. Fossil evidence from Baryonyx even preserves fish remains within the ribcage, providing direct insight into the feeding habits of early spinosaurids.

As spinosaurids spread into Africa and South America, they diversified and became increasingly specialized. Forms such as Suchomimus from Niger retained a body plan similar to early spinosaurids but reached larger sizes and showed further elongation of the skull. These animals appear to represent an intermediate stage—still competent terrestrial predators, but increasingly tied to aquatic food sources.

Spinosaurus represents the most extreme endpoint of this evolutionary trend. Compared to its relatives, it shows dramatic modifications: shortened hind limbs, unusually dense bones, a tall and laterally compressed swimming tail, and the iconic dorsal sail. These traits suggest that natural selection favored individuals better adapted for stability, maneuverability, and feeding within aquatic environments rather than speed or endurance on land.

Rather than evolving in direct competition with massive land predators such as Carcharodontosaurus, Spinosaurus likely avoided ecological overlap by exploiting a different niche altogether. Abundant fish and aquatic prey within Cretaceous river systems provided an opportunity for spinosaurids to specialize, and Spinosaurus ultimately became the dominant predator within that realm.

The evolutionary history of Spinosaurus highlights the remarkable ecological flexibility of dinosaurs. Far from being constrained to a single body plan or lifestyle, theropods explored a wide range of strategies—and in doing so, produced one of the most unusual and enigmatic predators ever to walk, wade, and swim through the prehistoric world.

More than a century after its discovery, Spinosaurus remains one of the most enigmatic and compelling dinosaurs ever studied. Unlike many famous prehistoric animals whose stories have gradually stabilized as new fossils accumulated, Spinosaurus has done the opposite—becoming more complex, more controversial, and more fascinating with every major discovery.

Its strange anatomy, from the towering sail and crocodile-like skull to the dense bones and swimming-adapted tail, reflects a predator shaped by rivers rather than plains. Its diet, feeding strategies, and probable semi-aquatic lifestyle reveal a dinosaur that challenged the limits of what theropods could be. Within the crowded ecosystems of Cretaceous North Africa, Spinosaurus carved out a unique role, exploiting aquatic resources that few other giant predators could reach.

At the same time, the fragmentary nature of its fossil record serves as a reminder of how science works at the edges of knowledge. The loss of key fossils, the mixing of bones in river deposits, and the ongoing debates over classification and behavior ensure that Spinosaurus will remain a subject of active research for decades to come.

Rather than a static icon, Spinosaurus is a living case study in scientific revision—a dinosaur continually reshaped by new evidence and new ideas. As future discoveries emerge from the deserts of North Africa and beyond, the river dragon’s story will continue to evolve, reminding us that the prehistoric world was not only stranger than we imagine, but stranger than we can yet fully know.

Unlike most large theropods, Spinosaurus was not designed for bone-crushing bites or high-speed pursuit. Its jaws were long and narrow, packed with smooth, conical teeth ideal for gripping slippery prey. Its nostrils sat far back on the skull, allowing it to breathe while much of its snout was submerged. Its bones were unusually dense—more like those of penguins or hippos than typical dinosaurs—helping counteract buoyancy in water. Even its massive tail, once thought to be ordinary, is now known to have been tall and laterally compressed, forming a powerful swimming organ unlike anything seen in other non-avian dinosaurs.

Perhaps most iconic of all was the enormous sail that rose from its back, formed by elongated neural spines that could exceed five feet in height. Whether used for display, thermoregulation, species recognition, or some combination of functions, the sail ensured that Spinosaurus would have been an unmistakable presence along the waterways of Cretaceous Africa.

What makes Spinosaurus especially compelling is not just how strange it was, but how often it has forced scientists to rethink their assumptions. Few dinosaurs have been reconstructed so many times—or so differently. Over the past century, Spinosaurus has transformed from a vaguely known sail-backed curiosity into the centerpiece of one of paleontology’s most intense debates: could a dinosaur truly live and hunt in the water?

Once a footnote known from fragments and wartime photographs, Spinosaurus is now a symbol of scientific revision. Each new discovery—from shortened hind limbs to swimming-adapted tails—has added complexity rather than clarity. More than any other dinosaur, Spinosaurus stands as a reminder that the prehistoric world was far stranger, more experimental, and more diverse than our imaginations once allowed.

A Theropod Giant Unlike Any Other

Spinosaurus is currently regarded as the longest known carnivorous dinosaur, with length estimates ranging from about 14 to over 15 meters (46–50+ feet), and possibly more depending on reconstruction. In sheer linear size, it exceeded even Tyrannosaurus rex, though it was built very differently. Weight estimates are more uncertain due to its unusual proportions, but most recent studies suggest Spinosaurus weighed roughly 6 to 9 metric tons—comparable to, or slightly lighter than, the largest T. rex specimens despite being significantly longer. Its elongated body, neck, and tail gave it a low, stretched silhouette unlike any other theropod, emphasizing length over bulk.

One of the most striking features of Spinosaurus was the enormous sail that rose from its back, formed by elongated neural spines extending from the vertebrae. In some individuals, these spines exceeded five feet in height, meaning the sail alone could rival the height of an adult human. Combined with its overall body size, this would have made Spinosaurus one of the tallest dinosaurs when viewed in profile. The function of the sail has been widely debated, with hypotheses ranging from visual display and species recognition to thermoregulation or even structural support for a low, fleshy hump. It is likely that the sail served multiple roles, shifting in importance depending on behavior, age, or environment.

The skull of Spinosaurus was long, narrow, and low, reaching lengths of over 1.6 meters (more than five feet) in some estimates—longer than the skull of T. rex. Its jaws were lined with smooth, conical teeth lacking serrations, ideal for gripping fish rather than tearing flesh. The snout was reinforced at the front, and the nostrils were positioned far back on the skull—an adaptation that allowed the animal to breathe while much of its snout was submerged in water.

The rest of the skeleton was just as unusual. Spinosaurus possessed unusually dense bones, a condition known as pachyostosis, which reduced buoyancy and helped stabilize the animal in water. Its hind limbs were short relative to body size, especially for an animal of such length, suggesting limited efficiency in fast terrestrial locomotion. In contrast, the tail was long, deep, and laterally compressed, forming a powerful swimming organ capable of generating propulsion in water.

Taken together, these traits—extreme length, massive but lightly built frame, towering sail, specialized skull, dense bones, reduced legs, and swimming tail—mark Spinosaurus as one of the most anatomically specialized dinosaurs ever discovered. Rather than excelling at speed or brute force, it was built for control, stability, and dominance in river-dominated environments.

Discovery in a Lost World

Ernst Stromer and the First Spinosaurus

Spinosaurus was first described in 1915 by German paleontologist Ernst Stromer von Reichenbach, based on fossils recovered from the Bahariya Formation of Egypt. These remains included parts of the skull, vertebrae, ribs, and pelvis—enough to establish a truly bizarre new theropod. Stromer named it Spinosaurus, meaning “Egyptian spine lizard.”

Tragically, the original fossils were housed in Munich and destroyed during an Allied bombing raid in 1944. For decades afterward, Spinosaurus existed only in Stromer’s detailed notes, photographs, and illustrations. This loss turned Spinosaurus into something of a ghost—famous, intriguing, but frustratingly incomplete.

A Fragmentary Fossil Record

The fossil record of Spinosaurus is one of the most challenging and controversial of any famous dinosaur. Unlike animals known from complete or near-complete skeletons, Spinosaurus is reconstructed from a patchwork of fossils collected over more than a century, from multiple countries, formations, and geological contexts. No single individual preserves the full skeleton, and many bones attributed to Spinosaurus have never been found in direct association with one another.

This fragmentary record is not merely inconvenient—it is central to why Spinosaurus has been so frequently reinterpreted. Each new discovery has the potential to dramatically alter reconstructions, because entire regions of the skeleton remain poorly known or entirely absent from the fossil record.

The Lost Egyptian Holotype

The original fossils described by Ernst Stromer from Egypt’s Bahariya Formation formed the foundation of everything known about Spinosaurus for decades. These remains included portions of the skull, distinctive sail-bearing vertebrae, ribs, gastralia, and elements of the pelvis. Stromer’s careful descriptions and photographs revealed a theropod unlike any other, but even this original material was incomplete.

The destruction of the holotype during World War II created a unique scientific problem. Because the original bones no longer exist, modern researchers must rely on Stromer’s records to interpret new material. This has complicated efforts to confirm whether later discoveries perfectly match the original animal or represent variation within a broader spinosaurid group.

North African Material and Ongoing Debate

Throughout the mid-to-late 20th century, isolated teeth and bones attributed to Spinosaurus were recovered across North Africa, particularly in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Egypt. Many of these fossils came from river-deposited sediments, consistent with an aquatic or semi-aquatic lifestyle. However, isolated spinosaurid teeth are notoriously difficult to assign to genus or species, leading to debates over misidentification and over-attribution.

Some material historically labeled as Spinosaurus has since been reassigned to other spinosaurids or deemed indeterminate. This has fueled skepticism, with some researchers questioning whether Spinosaurus was being reconstructed from a mixture of multiple related animals rather than a single coherent form.

The Kem Kem Discoveries

The most significant expansion of the Spinosaurus fossil record has come from the Kem Kem Beds of southeastern Morocco. Here, numerous skeletal elements—including vertebrae, limb bones, and parts of the tail—have been recovered from Cenomanian-aged deposits. While often found disarticulated, these fossils provide crucial insights into body proportions and adaptations.

In particular, discoveries of shortened hind limbs and an unusually tall, laterally compressed tail revolutionized interpretations of Spinosaurus anatomy. These finds suggested an animal with limited terrestrial locomotion but enhanced swimming ability, reinforcing the idea that Spinosaurus occupied a unique ecological niche among dinosaurs.

A Composite Dinosaur

Modern reconstructions of Spinosaurus are necessarily composite, drawing from multiple individuals and localities. This approach is not unique in paleontology, but it carries special risks when applied to an animal as unusual as Spinosaurus. Small errors or misassignments can have outsized effects on interpretations of posture, locomotion, and lifestyle.

As a result, Spinosaurus remains one of the most fluid dinosaurs in scientific visualization. New fossils continue to refine—and sometimes overturn—previous assumptions. Rather than a weakness, this ongoing revision highlights the dynamic nature of paleontology, where even the most famous dinosaurs can still be fundamentally redefined by a single bone.

The Kem Kem Beds: A River of Giants

Understanding Spinosaurus requires understanding the world it lived in. Much of what we know about its anatomy, behavior, and ecological role comes not just from its bones, but from the environment preserved around them. For this reason, the Kem Kem Beds of southeastern Morocco are central to any discussion of Spinosaurus—they represent the richest source of fossils attributed to this animal and provide critical context for interpreting how it lived.

The Kem Kem Beds date to the Cenomanian stage of the Late Cretaceous, approximately 95 million years ago. At the time, this region was not the arid desert seen today, but a vast, low-lying river system draining into the Tethys Sea. Broad rivers, seasonal floodplains, wetlands, and coastal lagoons dominated the landscape, creating an ecosystem exceptionally rich in aquatic life.

This environment supported one of the most predator-heavy ecosystems ever discovered in the fossil record. Enormous fish, including sawfish and giant coelacanths, were abundant. Massive crocodyliforms such as Sarcosuchus patrolled the waterways, while turtles and lungfish thrived in quieter channels. Pterosaurs soared overhead, and multiple species of large theropod dinosaurs stalked the floodplains.

Among these predators were Carcharodontosaurus, a land-dominating giant adapted for hunting large dinosaurs, and Deltadromeus, a long-legged, lightly built theropod likely specialized for speed. The coexistence of so many large carnivores suggests strong ecological partitioning, with each predator exploiting a different food source or habitat.

Within this crowded and dangerous ecosystem, Spinosaurus appears to have occupied a unique role. Its anatomy is ideally suited for exploiting aquatic prey that other theropods could not efficiently access. By hunting primarily in rivers and wetlands, Spinosaurus may have reduced direct competition with terrestrial predators while taking advantage of an abundant and renewable food source.

The Kem Kem Beds also help explain why Spinosaurus evolved such extreme specializations. A river system rich in large fish would favor predators capable of swimming, wading, and maintaining stability in water. Over time, these pressures likely shaped the unusual body plan seen in Spinosaurus, reinforcing its status as a river-dwelling specialist rather than a generalist land predator.

Because many Spinosaurus fossils come from disarticulated river deposits, the Kem Kem Beds also illustrate the challenges of reconstructing the animal. Bones transported by water are often scattered and mixed with remains of other animals, complicating efforts to associate skeletal elements. Nevertheless, the sheer volume of material from this region has made it indispensable to modern reconstructions of Spinosaurus.

Diet and Feeding: Master of the Rivers

To understand Spinosaurus, one must picture it not charging across open ground, but standing motionless in a river channel, water lapping against its flanks, jaws poised just above the surface. Feeding was not simply one aspect of its biology—it was the organizing principle around which its entire body was built.

Unlike most giant theropods, whose skulls were optimized for tearing flesh and crushing bone, Spinosaurus evolved into a specialist hunter of aquatic prey. Its long, narrow snout cut cleanly through water, reducing resistance and allowing rapid, precise strikes. This was a predator shaped by patience and positioning rather than raw power.

Its jaws were lined with smooth, conical teeth—dozens of them—lacking the sharp serrations seen in meat-slicing dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus. These teeth functioned less like knives and more like spikes, ideal for gripping slippery, struggling fish. Once clamped shut, escape would have been nearly impossible. The reinforced tip of the snout helped absorb twisting forces as prey thrashed, much like the jaws of modern crocodilians and gharials.

One remarkable consequence of this feeding strategy is how common Spinosaurus teeth are in the fossil record. Like crocodiles today, Spinosaurus continuously shed and replaced its teeth throughout its life. Teeth lost during feeding—snapped off, loosened, or naturally replaced—would sink into river sediments, where they fossilized in enormous numbers. This constant tooth replacement explains why isolated Spinosaurus teeth are among the most frequently found dinosaur fossils in North Africa, even when bones are rare.

These teeth, often beautifully preserved, offer critical insight into the animal’s diet and behavior. Their rounded cross-sections, enamel texture, and lack of wear from bone-crushing all reinforce the picture of a predator feeding primarily on fish rather than large terrestrial animals.

Evidence from close relatives strengthens this interpretation. Fossils of Baryonyx preserve fish scales within the ribcage, while spinosaurid bite marks have been found on fossil fish bones. Given the near-identical skull and tooth design, there is little doubt that fish formed the backbone of Spinosaurus’ diet.

Feeding likely involved a mix of wading and slow swimming. Dense limb bones helped stabilize the body in water, preventing excessive buoyancy, while the tall, laterally compressed tail provided fine control and propulsion. With its nostrils positioned far back on the skull, Spinosaurus could breathe while much of its snout remained submerged—an ideal setup for ambush hunting in murky rivers.

Although fish were its primary target, Spinosaurus was almost certainly opportunistic. Small to medium-sized dinosaurs, turtles, pterosaurs near the water’s edge, and carrion would not have been ignored. Like modern crocodiles, it likely took advantage of easy meals rather than engaging in risky confrontations. Its jaw mechanics suggest it was poorly suited for prolonged struggles with large, heavily built prey, favoring quick strikes and minimal resistance instead.

In the predator-rich ecosystems of the Kem Kem Beds, this feeding strategy was key to survival. By specializing in aquatic prey, Spinosaurus avoided direct competition with massive land predators such as Carcharodontosaurus. The rivers provided a renewable, protein-rich food source that few other dinosaurs could exploit efficiently.

In this way, the diet of Spinosaurus was far more than a curiosity. It was the foundation of its anatomy, its behavior, and its success—a river predator perfectly tuned to a world of flowing water, shifting channels, and endless schools of fish.

The Aquatic Dinosaur Debate

Few dinosaurs have stirred as much scientific argument as Spinosaurus, and at the heart of that debate lies a deceptively simple question: how much time did it actually spend in the water?

For much of the 20th century, the answer seemed obvious—dinosaurs, by definition, were land animals. Early paleontologists worked within that assumption, and Spinosaurus was no exception. Despite its crocodile-like skull and fish-eating teeth, it was typically reconstructed as a shoreline predator: a dinosaur that hunted fish along riverbanks but lived, walked, and moved much like other giant theropods.

That picture began to erode as new fossils filled in the blanks left by the destroyed original material. Shortened hind limbs emerged from the rock, raising immediate questions about how efficiently Spinosaurus could move on land. Studies of its bones revealed something even more surprising—they were unusually dense, heavier than those of most dinosaurs, a trait shared by many animals that spend much of their lives in water. Chemical signatures locked within its teeth told the same story. By analyzing stable oxygen isotopes preserved in Spinosaurus tooth enamel, researchers were able to compare its chemical profile with those of animals living in the same ecosystem. The results showed that Spinosaurus clustered closely with aquatic and semi-aquatic animals—such as crocodilians and large fish—rather than with land-dwelling theropods. Because tooth enamel forms slowly and records the chemistry of an animal’s drinking water and prey over time, these isotopic signatures suggest that Spinosaurus spent a significant portion of its life in aquatic environments, not merely visiting rivers occasionally but living within them as a regular part of its ecology.

The debate reached a turning point with the discovery of Spinosaurus tail vertebrae unlike anything previously known in a theropod. Tall neural spines and elongated chevrons formed a deep, laterally compressed tail capable of pushing against water. For some researchers, this was the missing piece of the puzzle—a dinosaur not merely associated with water, but one capable of swimming.

The idea of a truly aquatic dinosaur, however, was bound to invite skepticism. Critics argued that adaptation does not imply exclusivity. Dense bones and a swimming-capable tail, they noted, do not automatically make an animal a pursuit swimmer. Comparisons were drawn to hippos and other semi-aquatic mammals that spend hours submerged yet remain dependent on land.

Adaptions For A (Semi)-Aquatic Lifestyle

Retracted nostrils positioned high on the skull

Unlike most theropods, Spinosaurus had small nostrils placed far back on its snout — an advantage when breathing while much of its head was submerged in water.

Pressure-sensing neurovascular openings - Tiny neurovascular canals at the tip of the snout resemble those in modern crocodilians, where they house receptors that detect water movement. This may have helped Spinosaurus sense nearby fish.

Interlocking conical teeth - Its giant, slanted, conical teeth — ideal for gripping fish — would have worked like built-in fishhooks.

Long neck and trunk shifting body balance forward - A stretched neck and torso moved the center of mass ahead of the hips — great for hunting in water, less ideal for sustained land locomotion.

Robust forelimbs with curved claws - These powerful arms, with blade-like claws, may have helped Spinosaurus hook or slice slippery prey out of water.

Small pelvis and shortened hind limbs - The pelvic girdle was reduced and the hind legs were comparatively short — traits convergent with early whales and other animals that adapted from land into water.

Dense limb bones - Unlike most theropods with hollow bones, Spinosaurus had osteosclerotic bones (solid and heavy) that helped counteract buoyancy — just as seen in penguins and other aquatic animals.

Feet built for mud and shallow water - The bones of its feet were long and flat, similar to shorebirds that traverse soft ground. Some researchers propose Spinosaurus may even have had webbing, helping it walk on muddy banks or paddle.

Flexible, wave-like tail anatomy - A tail with loosely connected bones could bend in a wave-like fashion, similar to how fish and other swimming animals generate thrust.

Today, the debate has shifted away from absolutes. Rather than asking whether Spinosaurus was aquatic or terrestrial, most paleontologists now ask how aquatic it was. On that spectrum, Spinosaurus sits at the far extreme—more water-adapted than any other known non-avian dinosaur, even if it never fully abandoned the land. The controversy, far from being settled, continues to refine our understanding of how flexible and experimental dinosaur lifestyles could truly be.

Classification and Species of Spinosaurus

The classification of Spinosaurus is one of the most debated topics surrounding the genus, reflecting both its fragmentary fossil record and the complex history of spinosaurid discoveries in Africa and beyond. While Spinosaurus is universally recognized as a member of the family Spinosauridae, its internal taxonomy—how many species it contains and which fossils truly belong to it—remains unresolved.

Placement Within Spinosauridae

Spinosauridae is a distinctive group of theropod dinosaurs characterized by elongated, crocodile-like skulls, conical teeth, and a strong association with aquatic environments. Within this family, Spinosaurus is generally considered part of the subfamily Spinosaurinae, alongside close relatives such as Irritator and Oxalaia. Members of this subgroup tend to have longer, narrower snouts and more pronounced aquatic adaptations than baryonychines such as Baryonyx.

Within Spinosaurinae, Spinosaurus stands apart due to its immense size, extreme skeletal specializations, and iconic dorsal sail, making it the most derived and unusual member of the group.

The Type Species

The genus Spinosaurus was established on the basis of the Egyptian material described by Ernst Stromer in 1915. This material defines the type species, Spinosaurus aegyptiacus. Because the original fossils were destroyed during World War II, modern researchers must rely on Stromer’s descriptions and illustrations to evaluate whether newly discovered material truly belongs to the same species.

This loss has had lasting consequences. Without the ability to directly compare new fossils to the original bones, it is difficult to determine whether anatomical differences represent variation within a single species or evidence of multiple species within the genus.

Proposed Additional Species

Over the years, several additional species names have been proposed based on fragmentary material, most notably Spinosaurus maroccanus, named from isolated vertebrae discovered in Morocco. Many paleontologists consider this species dubious, arguing that the material lacks unique diagnostic features and may instead represent individual variation or belong to another spinosaurid entirely.

Other North African fossils have sometimes been attributed to Spinosaurus without being assigned to a specific species, further blurring taxonomic boundaries. Differences in vertebrae proportions, limb elements, and size have fueled speculation that more than one species of Spinosaurus may have existed across Africa during the Late Cretaceous.

Oxalaia and Broader Debate

The Brazilian genus Oxalaia has occasionally been suggested as a potential southern representative of Spinosaurus, based primarily on similarities in skull material. However, the remains of Oxalaia are extremely fragmentary, and most researchers currently prefer to keep it separate until more complete fossils are discovered.

This debate highlights a broader issue in spinosaurid classification: many fossils are known from isolated bones or teeth, which are difficult to assign confidently at the genus or species level. As a result, some material attributed to Spinosaurus may eventually be reassigned, while other fossils currently considered indeterminate could later expand the genus.

A Conservative Consensus

At present, most paleontologists adopt a conservative approach, recognizing Spinosaurus as a valid genus likely represented by a single well-established species, while acknowledging the possibility that future discoveries could reveal greater diversity. Until more complete, articulated skeletons are found, the internal classification of Spinosaurus will remain provisional.

This taxonomic uncertainty is not a weakness, but a reflection of how paleontology works at the frontier of discovery. As new fossils emerge, the classification of Spinosaurus—like its anatomy and lifestyle—may yet be rewritten.

Evolution and the Rise of the Spinosaurids

Spinosaurus belonged to the family Spinosauridae, a distinctive lineage of theropod dinosaurs that diverged early from other large carnivorous dinosaurs. While most giant theropods evolved toward powerful bites and fully terrestrial hunting strategies, spinosaurids followed a different evolutionary path—one increasingly shaped by life along rivers, lakes, and coastal environments.

The earliest known spinosaurids appear in the Early Cretaceous, with fossils found in Europe suggesting that the group may have originated there. Early members such as Baryonyx display a mix of traits: long, narrow jaws and conical teeth adapted for fish-eating, paired with relatively long hind limbs and proportions still well suited for walking on land. Fossil evidence from Baryonyx even preserves fish remains within the ribcage, providing direct insight into the feeding habits of early spinosaurids.

As spinosaurids spread into Africa and South America, they diversified and became increasingly specialized. Forms such as Suchomimus from Niger retained a body plan similar to early spinosaurids but reached larger sizes and showed further elongation of the skull. These animals appear to represent an intermediate stage—still competent terrestrial predators, but increasingly tied to aquatic food sources.

Spinosaurus represents the most extreme endpoint of this evolutionary trend. Compared to its relatives, it shows dramatic modifications: shortened hind limbs, unusually dense bones, a tall and laterally compressed swimming tail, and the iconic dorsal sail. These traits suggest that natural selection favored individuals better adapted for stability, maneuverability, and feeding within aquatic environments rather than speed or endurance on land.

Rather than evolving in direct competition with massive land predators such as Carcharodontosaurus, Spinosaurus likely avoided ecological overlap by exploiting a different niche altogether. Abundant fish and aquatic prey within Cretaceous river systems provided an opportunity for spinosaurids to specialize, and Spinosaurus ultimately became the dominant predator within that realm.

The evolutionary history of Spinosaurus highlights the remarkable ecological flexibility of dinosaurs. Far from being constrained to a single body plan or lifestyle, theropods explored a wide range of strategies—and in doing so, produced one of the most unusual and enigmatic predators ever to walk, wade, and swim through the prehistoric world.

The Ever-Changing Spinosaurus

More than a century after its discovery, Spinosaurus remains one of the most enigmatic and compelling dinosaurs ever studied. Unlike many famous prehistoric animals whose stories have gradually stabilized as new fossils accumulated, Spinosaurus has done the opposite—becoming more complex, more controversial, and more fascinating with every major discovery.

Its strange anatomy, from the towering sail and crocodile-like skull to the dense bones and swimming-adapted tail, reflects a predator shaped by rivers rather than plains. Its diet, feeding strategies, and probable semi-aquatic lifestyle reveal a dinosaur that challenged the limits of what theropods could be. Within the crowded ecosystems of Cretaceous North Africa, Spinosaurus carved out a unique role, exploiting aquatic resources that few other giant predators could reach.

At the same time, the fragmentary nature of its fossil record serves as a reminder of how science works at the edges of knowledge. The loss of key fossils, the mixing of bones in river deposits, and the ongoing debates over classification and behavior ensure that Spinosaurus will remain a subject of active research for decades to come.

Rather than a static icon, Spinosaurus is a living case study in scientific revision—a dinosaur continually reshaped by new evidence and new ideas. As future discoveries emerge from the deserts of North Africa and beyond, the river dragon’s story will continue to evolve, reminding us that the prehistoric world was not only stranger than we imagine, but stranger than we can yet fully know.

Reviews

Reviews