How Do Geodes Form?

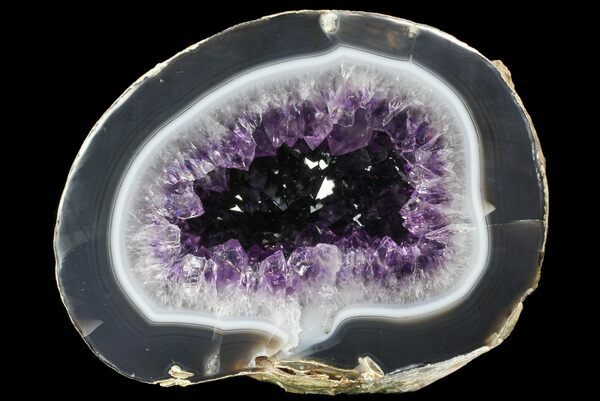

Geodes are more or less spherical or egg-shaped rocks containing a hollow cavity which is lined with crystals. They look ordinary from the outside—often resembling a plain nodule or rounded stone—but inside, they contain mineral formations that grew slowly in isolation. Think of them as natural rock-hosted crystal chambers, sealed off from the world until they are broken open.

Geodes begin as voids. The setting determines the shape of the cavity, but the story that fills it is almost always the same—water moves in, minerals crystallize out, and time does the rest. The most common mechanism starts when groundwater becomes enriched with dissolved silica, carbonates, or sulfates. This mineral-charged solution migrates through fractures, bedding planes, or porous rock until it reaches a hollow space. Inside the cavity, subtle environmental changes—cooling, evaporation, pressure drops, or chemical reactions—reduce the water’s ability to hold dissolved minerals. The excess begins to precipitate, forming microscopic mineral seeds on the interior wall. These nucleation points slowly build outward into crystals. Over thousands to millions of years, repeated flooding or fluid pulses deliver fresh mineral material, each wave adding incremental crystal growth. Eventually, the cavity becomes lined—sometimes filled—with druzy quartz, calcite, amethyst, or other minerals, forming the sparkling interiors that make geodes so distinctive.

1. Volcanic Geodes – Gas Bubbles Frozen in Lava

Volcanic geodes are the most visually iconic because their cavities are clean, rounded, and ideal for radial crystal growth. These start when rising magma releases dissolved gases (primarily water vapor, carbon dioxide, sulfur gases, and trace volatiles). If pressure drops rapidly—often near the top of a lava flow or within volcanic ash deposits—the gas forms bubbles that become trapped as the rock solidifies. Later, hydrothermal fluids or silica-rich groundwater seep into these vesicles. Many of the world’s best amethyst geodes formed this way, including the massive purple-lined geodes of Uruguay, where ancient basalt flows from the Paraná volcanic province cooled with abundant gas pockets that were later infused with mineralized fluids. Similarly, the famed Keokuk, Iowa quartz geodes originated in Mississippian-aged volcanic activity that produced bubble cavities later mineralized by silica-rich groundwater, creating chalcedony shells with quartz crystal cores.

2. Sedimentary Geodes – Voids in Layered Rock

Sedimentary geodes form in rock that was never molten. Instead, their cavities originate through softer, biological, or diagenetic processes. One major pathway is the decay of organic material—buried roots, tree branches, or animal burrows leave behind spaces after decomposition. Another comes from concretionary growth, where mineral precipitation forms a hard outer shell around a softer core that later dissolves, leaving a hollow interior. The famed septarian nodules of Madagascar begin as sedimentary concretions formed in marine mud, later fractured internally by shrinkage and mineralized by calcite and aragonite, though most septarians are technically “concretion geodes” rather than true crystal geodes. A clearer example of a sedimentary crystal geode is the Warfield Fossil Quarry geodes of Kentucky, which formed in limestone where internal voids were created by dissolution along bedding planes, later infilled by silica to form quartz linings.

3. Hydrothermal Geodes – Cavities from Water-Driven Dissolution

Hydrothermal geodes form when hot, mineral-saturated water dissolves rock to create cavities rather than filling pre-existing ones. These occur near geothermal systems, fault zones, or mineralized veins. The water removes soluble material like limestone, dolomite, or volcanic glass, carving irregular hollow spaces that are later lined with new crystal growth as the fluid chemistry shifts. Mexico’s Naica region produces hydrothermal selenite crystal pockets (though technically not geodes since they lack a full enclosing shell), but many of the agate-shelled geodes of Chihuahua and Sonora are true hydrothermal geodes, where silica deposition created a hard rind while interior fluids later precipitated quartz or calcite crystals.

4. Replacement Geodes – Shells from Mineral Transformation

Replacement geodes form when one mineral structure gradually converts into another while preserving the original exterior shape, often leaving internal voids during the process. Many calcite geodes form this way, where aragonite (a less stable form of calcium carbonate) slowly recrystallizes into calcite. During the transformation, micro-fractures and internal stress can create hollow zones that later host crystal growth. The silver-sheen calcite geodes from Morocco sometimes show this pathway, where early marine aragonite nodules altered into calcite, later dissolved internally and mineralized with secondary quartz crystals or carbonates.

Geodes thrive in regions with mineral-rich groundwater and long periods of geologic stability. Ancient flood basalts, limestone platforms, and volcanic rift provinces consistently produce the highest quality geodes because they provide both cavity-forming mechanisms and mineral delivery systems. For fossil and mineral retailers like FossilEra.com, volcanic amethyst geodes, Iowa quartz geodes, Moroccan replacement geodes, and Mexican agate-shelled quartz geodes represent the most commercially significant categories due to their durability, preparation potential, and display appeal.

Geodes often hide in plain sight. The best places to find them are areas where the host rock formed with natural voids or was later altered by mineral-rich groundwater. In volcanic regions, geodes weather out of basalt and accumulate in washes, on hillslopes, or within exposed lava flows. In sedimentary settings, they’re commonly found in limestone or shale outcrops, creek beds, and road cuts where groundwater once dissolved pockets in the rock. Deserts are especially productive because limited vegetation and constant erosion help reveal rounded nodules at the surface, many of which turn out to be geodes rather than solid concretions.

Breaking a geode is equal parts science and ceremony. Collectors typically use one of three methods: a rock hammer for field splitting, a handheld pipe-style geode cracker for controlled pressure, or a diamond-blade rock saw for precision cuts. The key is applying force evenly to avoid shattering the crystal cavity. In the field, a single confident strike around the widest circumference usually opens the stone along its natural weak point. Geode crackers work more gently, increasing pressure until the shell fractures with a clean break. For valuable or large geodes, a rock saw is the safest choice, allowing the exterior to be sliced without transmitting destructive shock into the cavity. No matter the method, the moment it opens reveals a world that may have taken millions of years to form—one of the most dramatic payoffs in fossil and mineral collecting.

Geodes begin as voids. The setting determines the shape of the cavity, but the story that fills it is almost always the same—water moves in, minerals crystallize out, and time does the rest. The most common mechanism starts when groundwater becomes enriched with dissolved silica, carbonates, or sulfates. This mineral-charged solution migrates through fractures, bedding planes, or porous rock until it reaches a hollow space. Inside the cavity, subtle environmental changes—cooling, evaporation, pressure drops, or chemical reactions—reduce the water’s ability to hold dissolved minerals. The excess begins to precipitate, forming microscopic mineral seeds on the interior wall. These nucleation points slowly build outward into crystals. Over thousands to millions of years, repeated flooding or fluid pulses deliver fresh mineral material, each wave adding incremental crystal growth. Eventually, the cavity becomes lined—sometimes filled—with druzy quartz, calcite, amethyst, or other minerals, forming the sparkling interiors that make geodes so distinctive.

Types of Geode Formation

1. Volcanic Geodes – Gas Bubbles Frozen in Lava

Volcanic geodes are the most visually iconic because their cavities are clean, rounded, and ideal for radial crystal growth. These start when rising magma releases dissolved gases (primarily water vapor, carbon dioxide, sulfur gases, and trace volatiles). If pressure drops rapidly—often near the top of a lava flow or within volcanic ash deposits—the gas forms bubbles that become trapped as the rock solidifies. Later, hydrothermal fluids or silica-rich groundwater seep into these vesicles. Many of the world’s best amethyst geodes formed this way, including the massive purple-lined geodes of Uruguay, where ancient basalt flows from the Paraná volcanic province cooled with abundant gas pockets that were later infused with mineralized fluids. Similarly, the famed Keokuk, Iowa quartz geodes originated in Mississippian-aged volcanic activity that produced bubble cavities later mineralized by silica-rich groundwater, creating chalcedony shells with quartz crystal cores.

2. Sedimentary Geodes – Voids in Layered Rock

Sedimentary geodes form in rock that was never molten. Instead, their cavities originate through softer, biological, or diagenetic processes. One major pathway is the decay of organic material—buried roots, tree branches, or animal burrows leave behind spaces after decomposition. Another comes from concretionary growth, where mineral precipitation forms a hard outer shell around a softer core that later dissolves, leaving a hollow interior. The famed septarian nodules of Madagascar begin as sedimentary concretions formed in marine mud, later fractured internally by shrinkage and mineralized by calcite and aragonite, though most septarians are technically “concretion geodes” rather than true crystal geodes. A clearer example of a sedimentary crystal geode is the Warfield Fossil Quarry geodes of Kentucky, which formed in limestone where internal voids were created by dissolution along bedding planes, later infilled by silica to form quartz linings.

3. Hydrothermal Geodes – Cavities from Water-Driven Dissolution

Hydrothermal geodes form when hot, mineral-saturated water dissolves rock to create cavities rather than filling pre-existing ones. These occur near geothermal systems, fault zones, or mineralized veins. The water removes soluble material like limestone, dolomite, or volcanic glass, carving irregular hollow spaces that are later lined with new crystal growth as the fluid chemistry shifts. Mexico’s Naica region produces hydrothermal selenite crystal pockets (though technically not geodes since they lack a full enclosing shell), but many of the agate-shelled geodes of Chihuahua and Sonora are true hydrothermal geodes, where silica deposition created a hard rind while interior fluids later precipitated quartz or calcite crystals.

4. Replacement Geodes – Shells from Mineral Transformation

Replacement geodes form when one mineral structure gradually converts into another while preserving the original exterior shape, often leaving internal voids during the process. Many calcite geodes form this way, where aragonite (a less stable form of calcium carbonate) slowly recrystallizes into calcite. During the transformation, micro-fractures and internal stress can create hollow zones that later host crystal growth. The silver-sheen calcite geodes from Morocco sometimes show this pathway, where early marine aragonite nodules altered into calcite, later dissolved internally and mineralized with secondary quartz crystals or carbonates.

Where the Best Geodes Form

Geodes thrive in regions with mineral-rich groundwater and long periods of geologic stability. Ancient flood basalts, limestone platforms, and volcanic rift provinces consistently produce the highest quality geodes because they provide both cavity-forming mechanisms and mineral delivery systems. For fossil and mineral retailers like FossilEra.com, volcanic amethyst geodes, Iowa quartz geodes, Moroccan replacement geodes, and Mexican agate-shelled quartz geodes represent the most commercially significant categories due to their durability, preparation potential, and display appeal.

Finding and Opening Geodes

Geodes often hide in plain sight. The best places to find them are areas where the host rock formed with natural voids or was later altered by mineral-rich groundwater. In volcanic regions, geodes weather out of basalt and accumulate in washes, on hillslopes, or within exposed lava flows. In sedimentary settings, they’re commonly found in limestone or shale outcrops, creek beds, and road cuts where groundwater once dissolved pockets in the rock. Deserts are especially productive because limited vegetation and constant erosion help reveal rounded nodules at the surface, many of which turn out to be geodes rather than solid concretions.

Breaking a geode is equal parts science and ceremony. Collectors typically use one of three methods: a rock hammer for field splitting, a handheld pipe-style geode cracker for controlled pressure, or a diamond-blade rock saw for precision cuts. The key is applying force evenly to avoid shattering the crystal cavity. In the field, a single confident strike around the widest circumference usually opens the stone along its natural weak point. Geode crackers work more gently, increasing pressure until the shell fractures with a clean break. For valuable or large geodes, a rock saw is the safest choice, allowing the exterior to be sliced without transmitting destructive shock into the cavity. No matter the method, the moment it opens reveals a world that may have taken millions of years to form—one of the most dramatic payoffs in fossil and mineral collecting.

Reviews

Reviews