Plesiosaurs: The Long-Necked Lords of the Mesozoic Seas

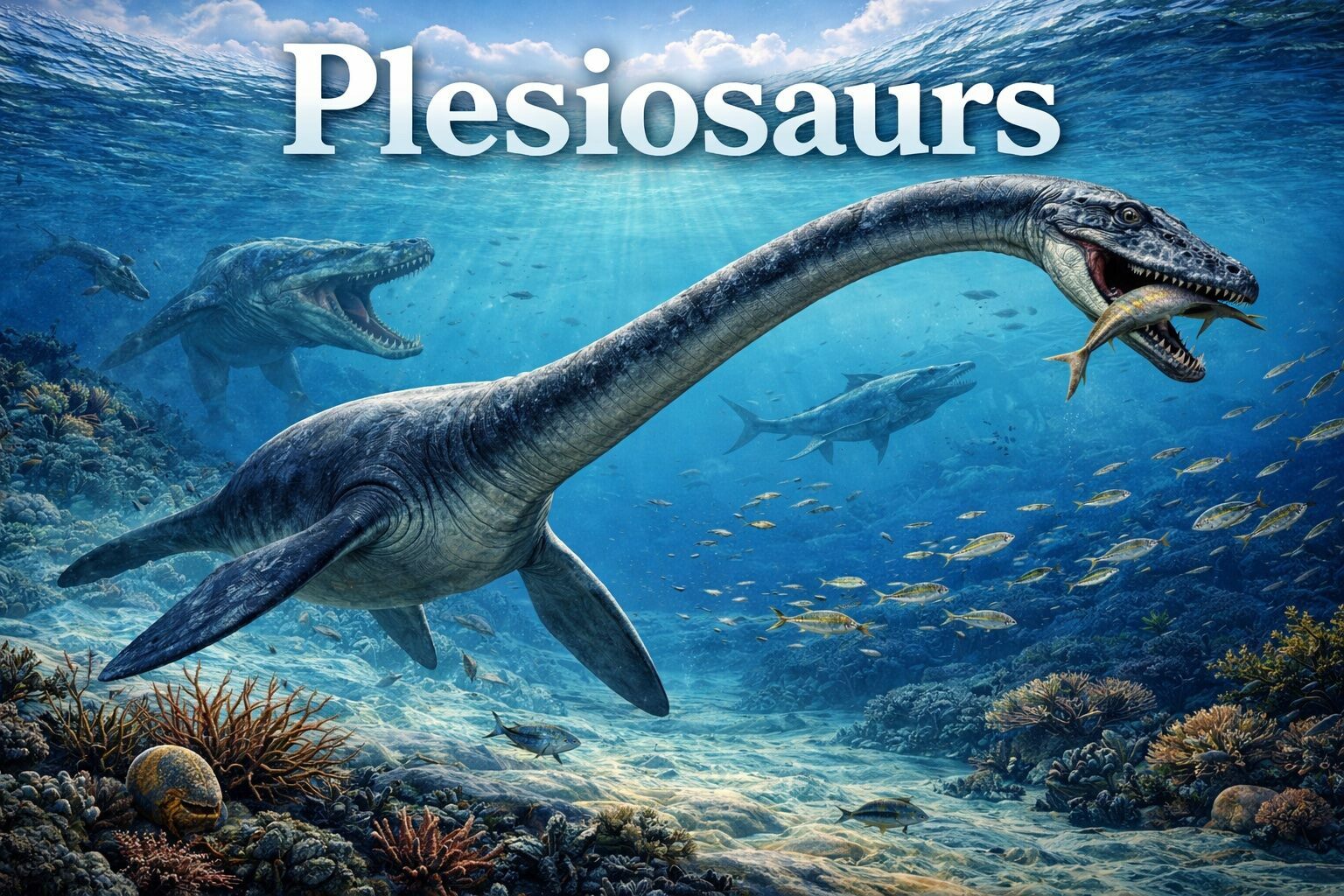

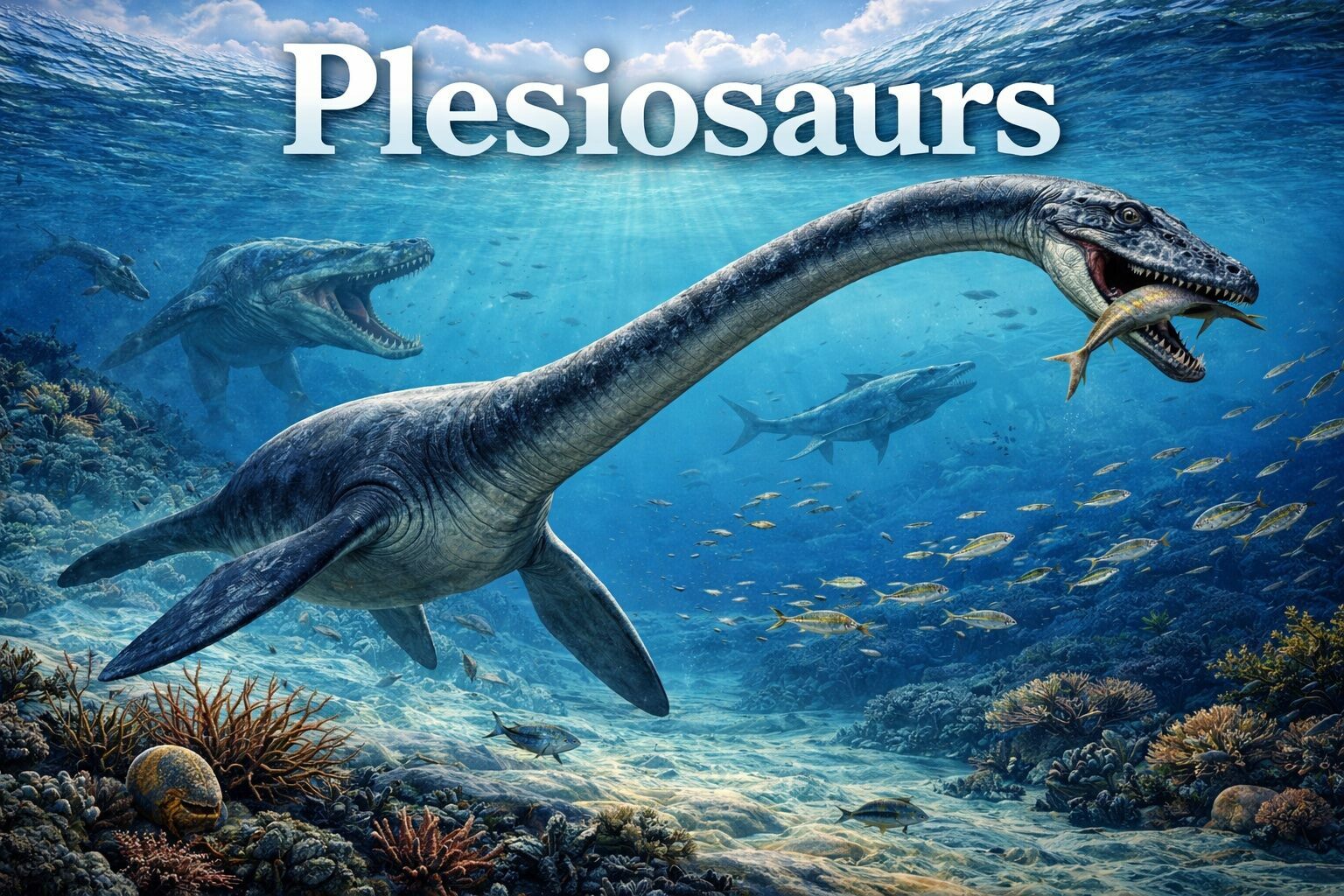

Few prehistoric animals are as instantly recognizable—or as endlessly fascinating—as plesiosaurs. With their long, flexible necks, compact bodies, powerful flippers, and tooth-filled jaws, plesiosaurs look almost designed to spark curiosity. They lived alongside dinosaurs, yet they were not dinosaurs at all. Instead, they ruled the oceans for over 135 million years, surviving multiple extinction events and diversifying into one of the most successful groups of marine reptiles in Earth’s history.

Some plesiosaurs had necks longer than their entire bodies, with as many as 70+ vertebrae, more than any other known vertebrate animal. Others went in a completely different direction—abandoning long necks in favor of massive skulls, short muscular necks, and immense bite strength. These short-necked forms are commonly known as pliosaurs, and they represent one of the most extreme predatory body plans ever to evolve in the sea.

Fossils of plesiosaurs—including pliosaurs—have been found on every continent, even Antarctica, revealing that they thrived in oceans that once connected the globe. Plesiosaurs also hold a special place in scientific and cultural history. They were among the first extinct reptiles ever reconstructed correctly, helped shape early ideas about extinction, and even inspired modern myths such as the Loch Ness Monster. But beyond their striking silhouette lies a complex evolutionary story of adaptation, experimentation, and survival in some of the most dangerous ecosystems Earth has ever known.

The fossil record of plesiosaurs is remarkably rich and geographically widespread. Their remains are most commonly preserved in marine sedimentary rocks, deposited on ancient seafloors that were later uplifted into deserts, mountains, and plains as continents shifted. Today, plesiosaur fossils are known from every continent, including Antarctica, revealing that these reptiles thrived in globally connected oceans for much of the Mesozoic Era.

Some of the earliest and most influential discoveries came from England’s Jurassic Coast, where coastal erosion continually exposes fossil-rich Jurassic rocks. In the early 19th century, fragmentary remains of strange marine reptiles puzzled scientists—vertebrae unlike crocodiles, paddles unlike turtles, and skulls that defied easy comparison to any living animal. These discoveries culminated in the first nearly complete plesiosaur skeletons, which shocked the scientific world with their unprecedented anatomy.

One of the most important early plesiosaur finds was described in 1824 by William Conybeare, who formally named the group Plesiosaurus, meaning “near lizard.” The name reflected the belief at the time that plesiosaurs might be evolutionarily close to modern reptiles—an idea that would later evolve as paleontology matured. Conybeare’s reconstruction, with its long neck, small head, and four flippers, was revolutionary and marked one of the first accurate reconstructions of an extinct animal based on comparative anatomy.

Closely tied to these discoveries was the work of Mary Anning, whose extraordinary fossil finds along the Dorset coast provided many of the specimens that scientists studied. Although she was excluded from formal scientific circles due to her gender and class, her discoveries were foundational. Several early plesiosaur specimens—and later, important pliosaur material—originated from fossils she unearthed.

As additional material accumulated, paleontologists began to recognize that not all plesiosaurs shared the same body plan. Some fossils revealed short-necked, large-headed forms with enormous jaws and teeth adapted for crushing and tearing flesh. In 1841, Richard Owen coined the term Pliosaurus—meaning “more lizard”—to distinguish these powerful predators from their long-necked relatives. The name reflected Owen’s belief that these animals were even more reptile-like and formidable than classic plesiosaurs.

The Oxford Clay Formation soon became one of the most important windows into pliosaur evolution. From these Jurassic deposits emerged gigantic skulls, some exceeding two meters in length, armed with massive conical teeth. These finds revealed that pliosaurs were not merely variants of plesiosaurs, but apex predators capable of dominating marine ecosystems. Subsequent discoveries across Europe—including Germany, France, Norway, and Russia—reinforced this view, with well-preserved pliosaur skeletons documenting their immense size and power.

Beyond Europe, plesiosaur and pliosaur fossils have been recovered from the western United States, South America, Africa, Australia, and Antarctica. Particularly striking are Antarctic finds, which demonstrate that plesiosaurs inhabited cold, high-latitude seas and were far more ecologically adaptable than once believed.

One reason plesiosaurs fossilize so well is their dense skeletal construction. Unlike many marine animals with lightweight bones, plesiosaurs evolved heavy, compact bones that helped counteract lung buoyancy. This adaptation not only stabilized them underwater but also increased the likelihood of preservation after death. As a result, many specimens are preserved as articulated skeletons rather than scattered remains. Some even retain stomach contents, such as fish bones and cephalopod hooks, as well as gastroliths—smooth stones swallowed to aid digestion or fine-tune buoyancy.

All plesiosaurs shared a distinctive anatomical blueprint that set them apart from every other marine reptile that ever lived. Their bodies were broad, rigid, and barrel-shaped, built around a strong ribcage that resisted twisting. Unlike fish or ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs had short, relatively unimportant tails that played little role in propulsion. Instead, movement was driven almost entirely by their four large, paddle-shaped limbs.

These four flippers are one of the most remarkable features of plesiosaurs. Each limb was supported by an expanded set of bones, forming a stiff, hydrofoil-like structure rather than a flexible paddle. Plesiosaurs “flew” through the water using all four flippers in a coordinated motion, generating lift and thrust much like underwater wings. This mode of locomotion gave them exceptional maneuverability, stability, and control, allowing precise turns, hovering, and sudden bursts of speed—advantages in complex marine environments.

Another key anatomical trait was their dense, compact bones. Unlike many marine animals that reduce bone mass to increase buoyancy, plesiosaurs evolved heavier skeletons that helped counteract lung buoyancy and maintain neutral balance underwater. This adaptation allowed them to remain stable at depth and is one reason their skeletons are so commonly preserved in the fossil record.

Two Body Plans, One Evolutionary Framework

Within this shared anatomical foundation, plesiosaurs evolved into two dramatically different morphologies, each representing a successful solution to marine predation.

Long-necked plesiosaurs possessed some of the most extreme neck elongation ever seen in vertebrates, with dozens—sometimes more than seventy—tightly interlocking cervical vertebrae. Despite appearances, these necks were relatively stiff and well supported by muscles and ligaments. The head at the end of this long neck was small and lightly built, armed with slender jaws and fine, needle-like teeth ideal for snaring slippery prey such as fish and squid.

This anatomy suggests a hunting strategy based on stealth rather than speed. The body could remain relatively motionless while the neck and head made rapid, precise strikes, minimizing disturbance in the water. Rather than acting like a swan-like fishing pole, the neck likely functioned as a subtle extension of the body, allowing prey to be captured before it detected the predator’s presence.

Short-necked plesiosaurs, known as pliosaurs, evolved in the opposite direction. Their necks were reduced to a compact, muscular column designed to brace the head during violent feeding events. In contrast to the delicate skulls of long-necked forms, pliosaurs had enormous, heavily built skulls with deep jaws and thick, conical teeth anchored by powerful roots. These teeth were not designed for finesse, but for gripping, crushing, and tearing flesh.

Pliosaurs were anatomically optimized for speed and power. Their shortened necks reduced drag, while their massive skulls housed enormous jaw muscles capable of delivering devastating bites. Combined with their powerful four-flipper propulsion, pliosaurs were pursuit predators capable of overtaking large fish, ammonites, and even other marine reptiles—including long-necked plesiosaurs.

Although behavior does not fossilize directly, plesiosaurs leave behind a surprisingly rich trail of evidence that allows paleontologists to reconstruct how they lived—and, crucially, what they ate. Anatomy, stomach contents, bite marks, and wear patterns on teeth all point to plesiosaurs being active predators, with diets that varied dramatically depending on body type.

Long-necked plesiosaurs were primarily fish- and cephalopod-eaters. Fossilized stomach contents have revealed fish bones, scales, and the chitinous hooks of squid-like animals (belemnites), confirming a diet dominated by small, fast-moving prey. Their slender jaws and needle-like teeth were perfectly suited for grasping slippery animals rather than crushing hard shells. The long neck likely allowed these plesiosaurs to approach prey with minimal disturbance. By keeping the bulky body farther away, they could strike quickly with the head, snatching fish before schools scattered. This feeding strategy mirrors that of modern ambush predators, emphasizing precision over brute force.

Short-necked plesiosaurs, or pliosaurs, occupied a far more aggressive ecological role. Fossil evidence indicates that they were apex predators, feeding on large fish, ammonites, sharks, and other marine reptiles—including long-necked plesiosaurs and even other pliosaurs. Bite marks on bones and partially digested reptile remains found near pliosaur fossils support this interpretation. Their massive skulls and thick, conical teeth were designed to withstand violent feeding. Unlike the delicate teeth of long-necked forms, pliosaur teeth could puncture thick flesh, crack bone, and grip struggling prey. Some pliosaur skulls show reinforced joints and muscle attachment sites consistent with exceptionally powerful bites, enabling them to dismember prey too large to swallow whole.

Many plesiosaur fossils contain gastroliths—smooth stones found within the ribcage. These stones may have served multiple purposes. One likely role was buoyancy control, helping the animal maintain stability while swimming or hovering in the water column. Another possibility is that gastroliths aided digestion, helping grind up soft-bodied prey or assisting with the breakdown of swallowed flesh.m Interestingly, gastroliths are more commonly found in long-necked plesiosaurs than in pliosaurs, which may reflect differences in feeding behavior. Long-necked forms often swallowed prey whole, while pliosaurs likely tore prey apart, reducing the need for internal processing stones.

The contrast in diet between plesiosaurs and pliosaurs reflects two very different behavioral strategies. Long-necked plesiosaurs were likely slow-cruising hunters, patrolling productive waters and ambushing small prey with minimal energy expenditure. Their anatomy suggests they were well adapted for sustained swimming and precision feeding rather than explosive speed.

Pliosaurs, by contrast, were active pursuit predators. Their streamlined bodies, reduced neck length, and powerful flippers allowed rapid acceleration and short bursts of high speed. These animals likely dominated open-water ecosystems, exerting top-down control similar to that of modern orcas or great white sharks.

Evidence that plesiosaurs gave live birth further reinforces their fully aquatic lifestyle. This reproductive strategy meant adults never needed to return to land, allowing both plesiosaurs and pliosaurs to exploit offshore feeding grounds throughout their lives. Juveniles were likely born relatively large and well developed, increasing their chances of survival in predator-rich oceans.

The evolutionary history of plesiosaurs is inseparable from their extraordinary diversity of size, shape, and ecological role. Over more than 135 million years—from the Early Jurassic to the end of the Cretaceous—plesiosaurs evolved into a wide array of forms that filled niches ranging from small, agile fish-hunters to colossal apex predators. Rather than representing a single “type” of animal, plesiosaurs formed a long-lived dynasty defined by continual experimentation within a successful marine body plan.

Early Evolution and the First Plesiosaurs

Plesiosaurs evolved from land-dwelling reptilian ancestors shortly after the end-Triassic extinction, a period when marine ecosystems were opening up to new predators. Early Jurassic plesiosaurs such as Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus already displayed the classic long-necked body plan, indicating that this distinctive anatomy evolved very rapidly once the lineage became fully aquatic.

At this stage, plesiosaurs were generally moderate in size, typically ranging from 10 to 15 feet (3–5 meters) long. These early forms fed primarily on fish and cephalopods and occupied mid-level predator roles in marine food webs dominated by ichthyosaurs and early sharks.

Divergence into Two Major Lineages

By the Early to Middle Jurassic, plesiosaurs had diverged into two major evolutionary trajectories:

Long-necked plesiosaurs, often grouped informally as “plesiosauroids”

Short-necked, large-headed plesiosaurs, known as pliosaurs

This split represents one of the most striking examples of evolutionary divergence within a single marine reptile group.

Long-necked forms reached extreme neck lengths in genera such as Elasmosaurus, whose neck alone could exceed 20 feet (6 meters) and contained more than 70 cervical vertebrae. These animals emphasized reach, stealth, and precision feeding. Despite their intimidating length, many were relatively lightly built and specialized for catching small, fast prey.

Pliosaurs, by contrast, pushed body size and predatory power to the extreme. Jurassic pliosaurs such as Liopleurodon, Pliosaurus, and Simolestes developed enormous skulls, sometimes over 2 meters long, and robust bodies capable of generating tremendous speed and bite force. These animals occupied the role of apex predators, feeding on large fish, ammonites, sharks, and other marine reptiles—including plesiosaurs themselves.

Size Extremes and Ecological Expansion

The size range of plesiosaurs expanded dramatically through time. Smaller species, roughly dolphin-sized, continued to thrive alongside giants, indicating niche partitioning rather than simple competitive replacement.

At the upper end of the scale, the largest pliosaurs reached lengths of 35–40 feet (10–12+ meters), rivaling or exceeding the size of modern killer whales. These animals dominated Jurassic seas and represent some of the most powerful predatory vertebrates ever to evolve in the ocean.

Meanwhile, long-necked plesiosaurs continued to diversify through the Cretaceous. Genera such as Styxosaurus and Hydrotherosaurus retained extreme neck elongation, while others adopted slightly shorter necks and more generalized feeding strategies. This flexibility allowed plesiosaurs to persist even as new competitors emerged.

Survival Through Change and the Rise of New Rivals

As the Cretaceous progressed, marine ecosystems underwent major changes. Ichthyosaurs declined and eventually disappeared, while mosasaurs rose to prominence as dominant marine predators. Despite this competition, plesiosaurs did not vanish immediately. Instead, they coexisted with mosasaurs, often occupying different ecological roles.

Long-necked plesiosaurs continued to exploit schooling fish and cephalopods, while some pliosaurs persisted as powerful predators, though generally smaller than their Jurassic predecessors. This prolonged coexistence highlights the adaptability of the plesiosaur body plan and its ability to remain competitive in changing oceans.

The End of a Long Reign

The story of plesiosaur evolution ended abruptly 66 million years ago with the end-Cretaceous mass extinction. The asteroid impact and resulting collapse of marine food webs eliminated both long-necked plesiosaurs and pliosaurs entirely. Unlike some marine groups that recovered or re-evolved similar forms, plesiosaurs left no direct descendants.

Some plesiosaurs had necks longer than their entire bodies, with as many as 70+ vertebrae, more than any other known vertebrate animal. Others went in a completely different direction—abandoning long necks in favor of massive skulls, short muscular necks, and immense bite strength. These short-necked forms are commonly known as pliosaurs, and they represent one of the most extreme predatory body plans ever to evolve in the sea.

Fossils of plesiosaurs—including pliosaurs—have been found on every continent, even Antarctica, revealing that they thrived in oceans that once connected the globe. Plesiosaurs also hold a special place in scientific and cultural history. They were among the first extinct reptiles ever reconstructed correctly, helped shape early ideas about extinction, and even inspired modern myths such as the Loch Ness Monster. But beyond their striking silhouette lies a complex evolutionary story of adaptation, experimentation, and survival in some of the most dangerous ecosystems Earth has ever known.

The Fossil Record: A Global Ocean Legacy

The fossil record of plesiosaurs is remarkably rich and geographically widespread. Their remains are most commonly preserved in marine sedimentary rocks, deposited on ancient seafloors that were later uplifted into deserts, mountains, and plains as continents shifted. Today, plesiosaur fossils are known from every continent, including Antarctica, revealing that these reptiles thrived in globally connected oceans for much of the Mesozoic Era.

Some of the earliest and most influential discoveries came from England’s Jurassic Coast, where coastal erosion continually exposes fossil-rich Jurassic rocks. In the early 19th century, fragmentary remains of strange marine reptiles puzzled scientists—vertebrae unlike crocodiles, paddles unlike turtles, and skulls that defied easy comparison to any living animal. These discoveries culminated in the first nearly complete plesiosaur skeletons, which shocked the scientific world with their unprecedented anatomy.

One of the most important early plesiosaur finds was described in 1824 by William Conybeare, who formally named the group Plesiosaurus, meaning “near lizard.” The name reflected the belief at the time that plesiosaurs might be evolutionarily close to modern reptiles—an idea that would later evolve as paleontology matured. Conybeare’s reconstruction, with its long neck, small head, and four flippers, was revolutionary and marked one of the first accurate reconstructions of an extinct animal based on comparative anatomy.

Closely tied to these discoveries was the work of Mary Anning, whose extraordinary fossil finds along the Dorset coast provided many of the specimens that scientists studied. Although she was excluded from formal scientific circles due to her gender and class, her discoveries were foundational. Several early plesiosaur specimens—and later, important pliosaur material—originated from fossils she unearthed.

As additional material accumulated, paleontologists began to recognize that not all plesiosaurs shared the same body plan. Some fossils revealed short-necked, large-headed forms with enormous jaws and teeth adapted for crushing and tearing flesh. In 1841, Richard Owen coined the term Pliosaurus—meaning “more lizard”—to distinguish these powerful predators from their long-necked relatives. The name reflected Owen’s belief that these animals were even more reptile-like and formidable than classic plesiosaurs.

The Oxford Clay Formation soon became one of the most important windows into pliosaur evolution. From these Jurassic deposits emerged gigantic skulls, some exceeding two meters in length, armed with massive conical teeth. These finds revealed that pliosaurs were not merely variants of plesiosaurs, but apex predators capable of dominating marine ecosystems. Subsequent discoveries across Europe—including Germany, France, Norway, and Russia—reinforced this view, with well-preserved pliosaur skeletons documenting their immense size and power.

Beyond Europe, plesiosaur and pliosaur fossils have been recovered from the western United States, South America, Africa, Australia, and Antarctica. Particularly striking are Antarctic finds, which demonstrate that plesiosaurs inhabited cold, high-latitude seas and were far more ecologically adaptable than once believed.

One reason plesiosaurs fossilize so well is their dense skeletal construction. Unlike many marine animals with lightweight bones, plesiosaurs evolved heavy, compact bones that helped counteract lung buoyancy. This adaptation not only stabilized them underwater but also increased the likelihood of preservation after death. As a result, many specimens are preserved as articulated skeletons rather than scattered remains. Some even retain stomach contents, such as fish bones and cephalopod hooks, as well as gastroliths—smooth stones swallowed to aid digestion or fine-tune buoyancy.

Plesiosaur Anatomy

All plesiosaurs shared a distinctive anatomical blueprint that set them apart from every other marine reptile that ever lived. Their bodies were broad, rigid, and barrel-shaped, built around a strong ribcage that resisted twisting. Unlike fish or ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs had short, relatively unimportant tails that played little role in propulsion. Instead, movement was driven almost entirely by their four large, paddle-shaped limbs.

These four flippers are one of the most remarkable features of plesiosaurs. Each limb was supported by an expanded set of bones, forming a stiff, hydrofoil-like structure rather than a flexible paddle. Plesiosaurs “flew” through the water using all four flippers in a coordinated motion, generating lift and thrust much like underwater wings. This mode of locomotion gave them exceptional maneuverability, stability, and control, allowing precise turns, hovering, and sudden bursts of speed—advantages in complex marine environments.

Another key anatomical trait was their dense, compact bones. Unlike many marine animals that reduce bone mass to increase buoyancy, plesiosaurs evolved heavier skeletons that helped counteract lung buoyancy and maintain neutral balance underwater. This adaptation allowed them to remain stable at depth and is one reason their skeletons are so commonly preserved in the fossil record.

Two Body Plans, One Evolutionary Framework

Within this shared anatomical foundation, plesiosaurs evolved into two dramatically different morphologies, each representing a successful solution to marine predation.

Long-necked plesiosaurs possessed some of the most extreme neck elongation ever seen in vertebrates, with dozens—sometimes more than seventy—tightly interlocking cervical vertebrae. Despite appearances, these necks were relatively stiff and well supported by muscles and ligaments. The head at the end of this long neck was small and lightly built, armed with slender jaws and fine, needle-like teeth ideal for snaring slippery prey such as fish and squid.

This anatomy suggests a hunting strategy based on stealth rather than speed. The body could remain relatively motionless while the neck and head made rapid, precise strikes, minimizing disturbance in the water. Rather than acting like a swan-like fishing pole, the neck likely functioned as a subtle extension of the body, allowing prey to be captured before it detected the predator’s presence.

Short-necked plesiosaurs, known as pliosaurs, evolved in the opposite direction. Their necks were reduced to a compact, muscular column designed to brace the head during violent feeding events. In contrast to the delicate skulls of long-necked forms, pliosaurs had enormous, heavily built skulls with deep jaws and thick, conical teeth anchored by powerful roots. These teeth were not designed for finesse, but for gripping, crushing, and tearing flesh.

Pliosaurs were anatomically optimized for speed and power. Their shortened necks reduced drag, while their massive skulls housed enormous jaw muscles capable of delivering devastating bites. Combined with their powerful four-flipper propulsion, pliosaurs were pursuit predators capable of overtaking large fish, ammonites, and even other marine reptiles—including long-necked plesiosaurs.

Behavior: Feeding Strategies and Life in the Open Ocean

Although behavior does not fossilize directly, plesiosaurs leave behind a surprisingly rich trail of evidence that allows paleontologists to reconstruct how they lived—and, crucially, what they ate. Anatomy, stomach contents, bite marks, and wear patterns on teeth all point to plesiosaurs being active predators, with diets that varied dramatically depending on body type.

Long-necked plesiosaurs were primarily fish- and cephalopod-eaters. Fossilized stomach contents have revealed fish bones, scales, and the chitinous hooks of squid-like animals (belemnites), confirming a diet dominated by small, fast-moving prey. Their slender jaws and needle-like teeth were perfectly suited for grasping slippery animals rather than crushing hard shells. The long neck likely allowed these plesiosaurs to approach prey with minimal disturbance. By keeping the bulky body farther away, they could strike quickly with the head, snatching fish before schools scattered. This feeding strategy mirrors that of modern ambush predators, emphasizing precision over brute force.

Short-necked plesiosaurs, or pliosaurs, occupied a far more aggressive ecological role. Fossil evidence indicates that they were apex predators, feeding on large fish, ammonites, sharks, and other marine reptiles—including long-necked plesiosaurs and even other pliosaurs. Bite marks on bones and partially digested reptile remains found near pliosaur fossils support this interpretation. Their massive skulls and thick, conical teeth were designed to withstand violent feeding. Unlike the delicate teeth of long-necked forms, pliosaur teeth could puncture thick flesh, crack bone, and grip struggling prey. Some pliosaur skulls show reinforced joints and muscle attachment sites consistent with exceptionally powerful bites, enabling them to dismember prey too large to swallow whole.

Many plesiosaur fossils contain gastroliths—smooth stones found within the ribcage. These stones may have served multiple purposes. One likely role was buoyancy control, helping the animal maintain stability while swimming or hovering in the water column. Another possibility is that gastroliths aided digestion, helping grind up soft-bodied prey or assisting with the breakdown of swallowed flesh.m Interestingly, gastroliths are more commonly found in long-necked plesiosaurs than in pliosaurs, which may reflect differences in feeding behavior. Long-necked forms often swallowed prey whole, while pliosaurs likely tore prey apart, reducing the need for internal processing stones.

The contrast in diet between plesiosaurs and pliosaurs reflects two very different behavioral strategies. Long-necked plesiosaurs were likely slow-cruising hunters, patrolling productive waters and ambushing small prey with minimal energy expenditure. Their anatomy suggests they were well adapted for sustained swimming and precision feeding rather than explosive speed.

Pliosaurs, by contrast, were active pursuit predators. Their streamlined bodies, reduced neck length, and powerful flippers allowed rapid acceleration and short bursts of high speed. These animals likely dominated open-water ecosystems, exerting top-down control similar to that of modern orcas or great white sharks.

Evidence that plesiosaurs gave live birth further reinforces their fully aquatic lifestyle. This reproductive strategy meant adults never needed to return to land, allowing both plesiosaurs and pliosaurs to exploit offshore feeding grounds throughout their lives. Juveniles were likely born relatively large and well developed, increasing their chances of survival in predator-rich oceans.

Size, Diversity, and Evolution

The evolutionary history of plesiosaurs is inseparable from their extraordinary diversity of size, shape, and ecological role. Over more than 135 million years—from the Early Jurassic to the end of the Cretaceous—plesiosaurs evolved into a wide array of forms that filled niches ranging from small, agile fish-hunters to colossal apex predators. Rather than representing a single “type” of animal, plesiosaurs formed a long-lived dynasty defined by continual experimentation within a successful marine body plan.

Early Evolution and the First Plesiosaurs

Plesiosaurs evolved from land-dwelling reptilian ancestors shortly after the end-Triassic extinction, a period when marine ecosystems were opening up to new predators. Early Jurassic plesiosaurs such as Plesiosaurus dolichodeirus already displayed the classic long-necked body plan, indicating that this distinctive anatomy evolved very rapidly once the lineage became fully aquatic.

At this stage, plesiosaurs were generally moderate in size, typically ranging from 10 to 15 feet (3–5 meters) long. These early forms fed primarily on fish and cephalopods and occupied mid-level predator roles in marine food webs dominated by ichthyosaurs and early sharks.

Divergence into Two Major Lineages

By the Early to Middle Jurassic, plesiosaurs had diverged into two major evolutionary trajectories:

This split represents one of the most striking examples of evolutionary divergence within a single marine reptile group.

Long-necked forms reached extreme neck lengths in genera such as Elasmosaurus, whose neck alone could exceed 20 feet (6 meters) and contained more than 70 cervical vertebrae. These animals emphasized reach, stealth, and precision feeding. Despite their intimidating length, many were relatively lightly built and specialized for catching small, fast prey.

Pliosaurs, by contrast, pushed body size and predatory power to the extreme. Jurassic pliosaurs such as Liopleurodon, Pliosaurus, and Simolestes developed enormous skulls, sometimes over 2 meters long, and robust bodies capable of generating tremendous speed and bite force. These animals occupied the role of apex predators, feeding on large fish, ammonites, sharks, and other marine reptiles—including plesiosaurs themselves.

Size Extremes and Ecological Expansion

The size range of plesiosaurs expanded dramatically through time. Smaller species, roughly dolphin-sized, continued to thrive alongside giants, indicating niche partitioning rather than simple competitive replacement.

At the upper end of the scale, the largest pliosaurs reached lengths of 35–40 feet (10–12+ meters), rivaling or exceeding the size of modern killer whales. These animals dominated Jurassic seas and represent some of the most powerful predatory vertebrates ever to evolve in the ocean.

Meanwhile, long-necked plesiosaurs continued to diversify through the Cretaceous. Genera such as Styxosaurus and Hydrotherosaurus retained extreme neck elongation, while others adopted slightly shorter necks and more generalized feeding strategies. This flexibility allowed plesiosaurs to persist even as new competitors emerged.

Survival Through Change and the Rise of New Rivals

As the Cretaceous progressed, marine ecosystems underwent major changes. Ichthyosaurs declined and eventually disappeared, while mosasaurs rose to prominence as dominant marine predators. Despite this competition, plesiosaurs did not vanish immediately. Instead, they coexisted with mosasaurs, often occupying different ecological roles.

Long-necked plesiosaurs continued to exploit schooling fish and cephalopods, while some pliosaurs persisted as powerful predators, though generally smaller than their Jurassic predecessors. This prolonged coexistence highlights the adaptability of the plesiosaur body plan and its ability to remain competitive in changing oceans.

The End of a Long Reign

The story of plesiosaur evolution ended abruptly 66 million years ago with the end-Cretaceous mass extinction. The asteroid impact and resulting collapse of marine food webs eliminated both long-necked plesiosaurs and pliosaurs entirely. Unlike some marine groups that recovered or re-evolved similar forms, plesiosaurs left no direct descendants.

Reviews

Reviews