Amethyst: Purple Quartz That Became a Legend

Amethyst is the most famous purple gemstone on Earth, and its story bridges hard science, ancient mythology, and royal history in a way few minerals can match. At its core, amethyst is simply quartz—silicon dioxide (SiO₂)—yet for thousands of years it was counted among the most valuable gemstones known to humanity. Until massive deposits were discovered in South America in the 18th and 19th centuries, amethyst was considered a cardinal gem, ranked alongside diamond, ruby, sapphire, and emerald. Kings wore it, clergy revered it, and entire cultures assigned it meanings tied to power, clarity, and protection.

Part of amethyst’s historical importance comes from its color. Purple has long been associated with royalty, authority, and the divine, largely because purple dyes were extraordinarily rare and expensive in the ancient world. Amethyst provided that same visual symbolism directly from nature. From carved amulets in ancient Egypt, to Greek and Roman engraved gems, to medieval bishop’s rings and European crown jewels, amethyst became inseparable from the visual language of leadership, spirituality, and restraint. Long before modern mineralogy existed, people recognized that this stone was something special.

Scientifically, amethyst’s color is every bit as fascinating as its history. Despite its regal appearance, amethyst is “just” quartz—but quartz altered by a precise and somewhat delicate set of conditions. Its purple coloration comes from trace amounts of iron incorporated into the quartz crystal lattice and later modified by natural irradiation from surrounding rocks. This irradiation rearranges electrons into what are known as color centers, producing hues that range from pale lilac to deep royal purple. Small differences in chemistry, radiation exposure, and growth temperature mean that even crystals growing side by side can display dramatically different colors or zoning.

Amethyst often records its own growth history in visible ways. Many crystals show color banding, phantoms, or sector zoning, which act like geological fingerprints—evidence of changes in fluid chemistry or environmental conditions during crystallization. Some specimens combine multiple growth phases, shifting from clear quartz to richly colored amethyst, while others display sharp boundaries between purple and colorless zones. These features make amethyst as interesting to mineral collectors and geologists as it is to jewelers.

One of the most remarkable aspects of amethyst is how its popularity survived the loss of its rarity. When vast deposits in Brazil and Uruguay entered global trade, amethyst was no longer reserved for royalty—but instead of fading into obscurity, it became one of the world’s most beloved gemstones and crystals. Its durability (Mohs hardness of 7), affordability, and stunning crystal forms allowed it to flourish in jewelry, mineral collections, and interior décor alike. Few gemstones have successfully made the transition from elite treasure to widely accessible natural art while retaining their mystique.

Today, amethyst is one of the most recognized and collected minerals on Earth. It is a February birthstone, a staple of museum and private collections, and a centerpiece of crystal displays ranging from small clusters to towering cathedral geodes. It forms in volcanic basalt cavities, hydrothermal veins, and mineral-rich fractures across nearly every continent. That extraordinary combination of scientific intrigue, visual drama, and deep cultural history is why amethyst continues to captivate—proof that even a common mineral, given the right conditions, can become legendary.

Properties Of Amethyst

Mineral group: Quartz (tectosilicate)

Formula: SiO₂

Hardness: 7 (Mohs) — durable enough for daily jewelry

Color: Light to Deep Purple

Crystal system: Trigonal (often seen as hexagonal prisms with pointed terminations)

Luster: Vitreous (glassy)

Amethyst geodes are nature’s crystal “rooms,” and they form in a surprisingly orderly sequence:

1. A cavity is created - Most famous amethyst geodes begin as gas bubbles in cooling lava flows (vesicles). Some form as dissolution cavities in other rocks, but basaltic bubbles are the classic origin.

2. The cavity gets sealed and mineralized - After the lava solidifies, circulating fluids enter the cavity through micro-fractures. Early on, the walls may receive a lining of chalcedony/agate (microcrystalline quartz) that seals the interior like waterproofing.

3. Quartz crystals grow inward - As silica continues to arrive, crystals nucleate on the walls and grow into the open space. Growth can happen in pulses—each pulse leaving subtle zoning, phantoms, or shifts in color.

4. Amethyst color develops - Iron incorporated during growth is later altered by natural radiation into the purple color centers. The most intensely colored crystals often require a narrow window of conditions—right trace chemistry, temperature, and radiation environment.

5. Late minerals may cap the story - Some geodes finish with minerals like calcite, gypsum, goethite/hematite, or other late-stage deposits. In big “cathedral” geodes, the sequence can be complex and spectacular.

Amethyst is found on every continent, but a handful of localities have become world-famous for producing crystals with distinctive colors, growth habits, and geological settings. These deposits not only define what collectors expect from high-quality amethyst, but also tell the story of how different environments shape one of the world’s most recognizable gemstones.

Uruguay

Uruguay is legendary for deep, richly saturated purple amethyst, commonly forming in basalt-hosted geodes. Many Uruguayan pieces show tight, well-formed crystals with strong color even in smaller points, which is why Uruguay is often the benchmark when people picture “royal purple” amethyst. Cathedral geodes from Uruguay can be dramatic: dark interiors, crisp crystal faces, and a dense, luxurious look. Another hallmark is how “finished” many Uruguayan geodes appear: thick agate/chalcedony linings, solid basalt shells, and sometimes additional minerals like calcite. From a collector’s perspective, Uruguay’s best material looks intense under normal indoor lighting—one reason it’s so prized for display pieces and statement décor.

Near Artigas in northern Uruguay, amethyst mining is a major geological and economic feature of the region, rooted in the ancient volcanic rocks of the basaltic traps. Here, silica-rich fluids once permeated gas bubbles within the lava flows, ultimately forming countless cavities lined with quartz that later became the stunning amethyst crystals the area is known for today. Miners in the region work both open exposures and shallow pits where geode-bearing basalt is accessible, carefully extracting the geodes by hand or with light machinery to avoid damaging the delicate crystal interiors. Because these geodes form in layered sequences—often with an outer agate or chalcedony lining and a rich core of purple quartz—experienced miners use geological markers and local knowledge to find the pockets most likely to yield richly colored material.

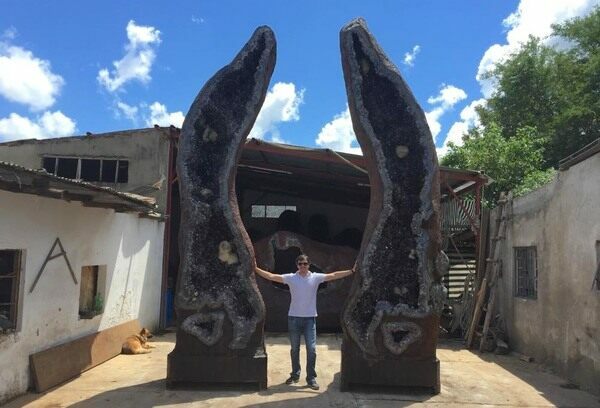

The mining operations around Artigas combine traditional techniques and community-based efforts with small-scale commercial activity. Unlike large industrial mines, many of the workings are family-run or cooperative in nature, with local diggers and traders playing a central role in the supply chain. After extraction, the geodes are typically split and cleaned on site or nearby, then sorted for size, color saturation, and crystal quality before entering the global market. Uruguayan amethyst is prized for its deep violet hues and strong saturation, and the Artigas region remains one of the most important sources of high-grade amethyst geodes for collectors, jewelers, and décor markets worldwide. The largest amethyst geodes in the world come from the deposits near Artigas.

Brazil

Brazil is the world’s most prolific amethyst producers by volume and variety. Brazilian amethyst ranges from pale lilac to strong purple and occurs in both geodes and other quartz-bearing environments. Brazilian geodes can be enormous, and many of the classic “cathedral” showpieces in shops and collections trace back to Brazilian volcanic provinces. Brazilian material in general tends to be lighter colored, but with larger crystals the Uruguay amethyst.

Brazil is also famous for material that responds to heat treatment—historically feeding a large share of the citrine market through heated amethyst. Collectors also seek Brazilian specimens that show interesting zoning, large crystal points, and associated agate linings. Because Brazil produces such a wide spectrum, it’s a locality where “Brazilian amethyst” can mean many looks—so the best approach is to describe the color and habit rather than rely on the country name alone.

Las Vigas, Mexico

Las Vigas (Veracruz, Mexico) is renowned among collectors for distinctive, often slender and elegant quartz crystals, frequently with amethyst coloration or amethyst zoning. Rather than cathedral geodes, Las Vigas is known for specimen-style clusters and individual crystals that can show beautiful transparency, sharp terminations, and character-rich growth habits.

What makes Las Vigas stand out is the collector vibe: crystals can have a “clean, architectural” look, sometimes with phantoms, zoning, or subtle color gradients. The material appeals to people who love classic mineral aesthetics—well-formed points and clusters—rather than only the big geode décor style.

South Africa (Cactus Quartz / Spirit Quartz)

South Africa’s famous “cactus quartz” (often also called spirit quartz) is a texture phenomenon: a central quartz crystal (or cluster) becomes covered in a sparkling layer of tiny drusy crystals, creating a bristly, glittering surface—hence “cactus.” Many pieces are white to smoky, but amethyst-tinted examples are especially popular because the purple hue adds depth to the already dazzling surface.

These specimens are often collected for their overall look rather than perfect single-crystal faces. The appeal is maximal sparkle and otherworldly surface geometry—like a crystal that’s been “frosted” by quartz itself. In display lighting, cactus quartz can look alive, because every tiny crystal catches light at a different angle.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Amethyst from the Democratic Republic of the Congo has gained increasing attention for its strong coloration and very large crystals. Material from the region commonly forms as clusters and crystal groups rather than large cathedral-style geodes, with well-developed points that display medium to deep purple hues. While not as historically famous as South American deposits, high-quality Congo amethyst can rival better-known sources in color and form, and its growing presence on the market has made it an increasingly important locality for modern collectors.

Thunder Bay, Ontario (Canada)

Thunder Bay amethyst is famous for its reddish iron staining and hematite inclusions, often giving crystals a warm, rusty contrast against the purple. This creates a distinct look compared with the cooler, saturated “cathedral” style from Uruguay. The result can be extremely photogenic: purple crystals with red-brown accents and a rugged, natural character.

Thunder Bay material is also celebrated for how it presents as a specimen mineral—clusters, points, and matrix pieces that feel like a slice of ancient geology rather than a polished décor product. Collectors often prize it for the locality identity: you can usually recognize Thunder Bay amethyst at a glance due to that iron-rich aesthetic.

North Carolina (USA)

North Carolina amethyst occurs in several geological contexts and is often collected as crystals and clusters rather than giant geodes. The state’s complex metamorphic and igneous history provides plenty of fractures and fluid pathways for quartz growth, and amethyst can appear as purple-tinted crystals in pockets, veins, and mineralized zones.

What makes North Carolina material appealing is the “local classic” status for U.S. collectors: it connects to a broader Appalachian mineral tradition—field collecting, pocket finds, and regional mineral localities. Pieces can vary widely in color intensity and habit, so North Carolina amethyst is often appreciated for individuality and provenance rather than one uniform signature look.

Amethyst occurs in a wide range of crystal habits and mixed-color forms, many of which are considered distinct varieties by collectors due to their unusual growth patterns or visual characteristics. These special forms record subtle changes in chemistry, temperature, or growth conditions during crystallization, making them scientifically interesting as well as visually distinctive. Some varieties are defined by internal structure and zoning, while others are defined by dramatic crystal habits that differ from the classic single-point amethyst crystal.

Chevron Amethyst - is one of the most recognizable patterned varieties. It displays bold V-shaped or zigzag bands formed by alternating layers of purple amethyst and white or milky quartz. These patterns develop when crystal growth occurs in rhythmic stages, with slight shifts in chemistry or clarity between phases. Chevron amethyst is commonly cut into slabs, cabochons, and carvings where the natural banding creates striking, graphic designs that clearly reveal the stone’s growth history.

Amethyst scepters - are prized crystal forms in which a second generation of quartz grows on top of an earlier crystal, creating a thicker, darker purple “cap” on a narrower stem. This overgrowth happens when growth conditions change and later fluids deposit new quartz preferentially at the crystal tip. The result is a dramatic, top-heavy crystal that looks almost sculptural. Scepter amethyst is especially valued by mineral collectors because it clearly shows multiple growth episodes frozen in a single crystal.

Cactus amethyst - also commonly called spirit quartz, is best known from South Africa and is defined by its sparkling, drusy surface. In this form, a central quartz crystal becomes coated with thousands of tiny secondary crystals, creating a rough, spiny texture reminiscent of a cactus. While many cactus quartz specimens are white or smoky, amethyst-colored examples are particularly sought after, combining the vibrant purple hue with intense surface sparkle. The texture results from rapid nucleation of quartz crystals on an existing crystal surface rather than continued growth of a single crystal face.

Ametrine - is a unique quartz variety that naturally combines both amethyst (purple) and citrine (yellow) within the same crystal. This striking color contrast forms when different parts of the crystal experience different oxidation states of iron and subtle temperature gradients during growth. The boundary between purple and yellow can be sharp or gradual, creating dramatic visual effects when cut. Natural ametrine is relatively uncommon and most famously associated with deposits in Bolivia, making it one of the most distinctive and scientifically interesting mixed-color forms of quartz.

Amethyst’s cultural career is almost unmatched for a gemstone. It has been prized across civilizations not only for beauty, but for what people believed it did.

The “not drunk” stone: classical origins

The name amethyst traces back to ancient Greek, commonly linked to the idea of being “not intoxicated.” In classical stories, amethyst was associated with sobriety and clarity of mind. Whether or not anyone truly expected a gem to counteract wine, the belief anchored amethyst as a stone of moderation—an antidote to excess—at a time when symbolism and medicine often blurred together.

Greek and Roman artisans carved amethyst into engraved gems, seals, and jewelry. Because quartz is hard and takes a fine polish, it worked beautifully for intaglios and cameos. Amethyst’s regal color also gave it an air of prestige: purple dyes were expensive and status-coded in many ancient societies, and gemstones that echoed those hues naturally picked up similar associations.

Medieval to Renaissance: faith, power, and protection

In Europe, amethyst became entwined with Christian symbolism, especially among clergy. Purple carried themes of penitence, devotion, and authority, so amethyst often appeared in ecclesiastical rings and ornaments. Over time, it developed a reputation for protection—against not only intoxication but also temptation, negative thoughts, and “bad influences.” These ideas weren’t fringe; they were woven into the broader medieval worldview where stones, metals, and planets were thought to share sympathetic connections.

During the Renaissance, amethyst stayed fashionable in high jewelry and courtly adornment. It was valued as a “noble” gem alongside sapphire, ruby, emerald, and diamond—especially before vast modern deposits made it more accessible. The moment large-scale South American sources entered global trade, amethyst shifted from ultra-elite to widely loved—without losing its aura.

Modern uses: jewelry, décor, collecting, and symbolism

Today, amethyst is used across a wide range of applications that highlight both its beauty and durability. In jewelry, it is commonly cut into faceted stones, cabochons, beads, and carvings, with its Mohs hardness of 7 making it well suited for regular wear, provided it is protected from hard impacts and prolonged exposure to intense heat. Beyond jewelry, amethyst is a popular decorative stone, appearing as dramatic geode “cathedrals,” crystal clusters, bookends, spheres, and large statement pieces, where its visual impact scales effortlessly from small accents to room-anchoring displays.

Amethyst is also highly regarded among mineral collectors, who value it for its diverse crystal habits, color zoning, internal phantoms, inclusions such as hematite, and the distinctive characteristics tied to specific localities. In addition, it remains a meaningful choice for symbolic gifting, long associated with calm, balance, and mental clarity, and widely recognized as a February birthstone in modern traditions. Amethyst’s greatest cultural achievement is its ability to feel both ancient and contemporary at the same time—equally at home in historic crown jewels and on a modern minimalist shelf.

Amethyst is a relatively durable gemstone with a Mohs hardness of 7, making it well suited for jewelry and display, but its color requires thoughtful care. One of the most important considerations is light exposure. Prolonged exposure to direct sunlight or intense artificial light can cause some amethyst—especially pale lilac or lightly saturated material—to gradually fade over time. This happens because ultraviolet light can disrupt the color centers created by iron and natural irradiation within the crystal structure. While deeply colored amethyst is generally more resistant, no amethyst is completely immune to long-term UV exposure.

For this reason, amethyst specimens and jewelry are best displayed away from sunny windows, skylights, and strong display lighting. Rotating display pieces, using indirect lighting, or placing specimens in shaded areas can significantly slow fading. When storing amethyst, keep it in a dark or low-light environment, such as a cabinet, drawer, or boxed display. Jewelry should be stored separately to avoid scratching and kept away from heat sources, as excessive heat can also alter or destroy amethyst’s purple color, sometimes turning it yellow or brown.

Cleaning amethyst is straightforward but should be done gently. Warm water, mild soap, and a soft brush are usually sufficient for removing dust or oils. Avoid harsh chemicals, prolonged soaking, and ultrasonic cleaners—especially for specimens with fractures, inclusions, or delicate crystal points. With proper care and mindful light exposure, amethyst can retain its rich purple color and natural beauty for generations.

Part of amethyst’s historical importance comes from its color. Purple has long been associated with royalty, authority, and the divine, largely because purple dyes were extraordinarily rare and expensive in the ancient world. Amethyst provided that same visual symbolism directly from nature. From carved amulets in ancient Egypt, to Greek and Roman engraved gems, to medieval bishop’s rings and European crown jewels, amethyst became inseparable from the visual language of leadership, spirituality, and restraint. Long before modern mineralogy existed, people recognized that this stone was something special.

Scientifically, amethyst’s color is every bit as fascinating as its history. Despite its regal appearance, amethyst is “just” quartz—but quartz altered by a precise and somewhat delicate set of conditions. Its purple coloration comes from trace amounts of iron incorporated into the quartz crystal lattice and later modified by natural irradiation from surrounding rocks. This irradiation rearranges electrons into what are known as color centers, producing hues that range from pale lilac to deep royal purple. Small differences in chemistry, radiation exposure, and growth temperature mean that even crystals growing side by side can display dramatically different colors or zoning.

Amethyst often records its own growth history in visible ways. Many crystals show color banding, phantoms, or sector zoning, which act like geological fingerprints—evidence of changes in fluid chemistry or environmental conditions during crystallization. Some specimens combine multiple growth phases, shifting from clear quartz to richly colored amethyst, while others display sharp boundaries between purple and colorless zones. These features make amethyst as interesting to mineral collectors and geologists as it is to jewelers.

One of the most remarkable aspects of amethyst is how its popularity survived the loss of its rarity. When vast deposits in Brazil and Uruguay entered global trade, amethyst was no longer reserved for royalty—but instead of fading into obscurity, it became one of the world’s most beloved gemstones and crystals. Its durability (Mohs hardness of 7), affordability, and stunning crystal forms allowed it to flourish in jewelry, mineral collections, and interior décor alike. Few gemstones have successfully made the transition from elite treasure to widely accessible natural art while retaining their mystique.

Today, amethyst is one of the most recognized and collected minerals on Earth. It is a February birthstone, a staple of museum and private collections, and a centerpiece of crystal displays ranging from small clusters to towering cathedral geodes. It forms in volcanic basalt cavities, hydrothermal veins, and mineral-rich fractures across nearly every continent. That extraordinary combination of scientific intrigue, visual drama, and deep cultural history is why amethyst continues to captivate—proof that even a common mineral, given the right conditions, can become legendary.

Properties Of Amethyst

Mineral group: Quartz (tectosilicate)

Formula: SiO₂

Hardness: 7 (Mohs) — durable enough for daily jewelry

Color: Light to Deep Purple

Crystal system: Trigonal (often seen as hexagonal prisms with pointed terminations)

Luster: Vitreous (glassy)

How Amethyst Geodes Form

Amethyst geodes are nature’s crystal “rooms,” and they form in a surprisingly orderly sequence:

1. A cavity is created - Most famous amethyst geodes begin as gas bubbles in cooling lava flows (vesicles). Some form as dissolution cavities in other rocks, but basaltic bubbles are the classic origin.

2. The cavity gets sealed and mineralized - After the lava solidifies, circulating fluids enter the cavity through micro-fractures. Early on, the walls may receive a lining of chalcedony/agate (microcrystalline quartz) that seals the interior like waterproofing.

3. Quartz crystals grow inward - As silica continues to arrive, crystals nucleate on the walls and grow into the open space. Growth can happen in pulses—each pulse leaving subtle zoning, phantoms, or shifts in color.

4. Amethyst color develops - Iron incorporated during growth is later altered by natural radiation into the purple color centers. The most intensely colored crystals often require a narrow window of conditions—right trace chemistry, temperature, and radiation environment.

5. Late minerals may cap the story - Some geodes finish with minerals like calcite, gypsum, goethite/hematite, or other late-stage deposits. In big “cathedral” geodes, the sequence can be complex and spectacular.

Famous Amethyst Localities

Amethyst is found on every continent, but a handful of localities have become world-famous for producing crystals with distinctive colors, growth habits, and geological settings. These deposits not only define what collectors expect from high-quality amethyst, but also tell the story of how different environments shape one of the world’s most recognizable gemstones.

Uruguay

Uruguay is legendary for deep, richly saturated purple amethyst, commonly forming in basalt-hosted geodes. Many Uruguayan pieces show tight, well-formed crystals with strong color even in smaller points, which is why Uruguay is often the benchmark when people picture “royal purple” amethyst. Cathedral geodes from Uruguay can be dramatic: dark interiors, crisp crystal faces, and a dense, luxurious look. Another hallmark is how “finished” many Uruguayan geodes appear: thick agate/chalcedony linings, solid basalt shells, and sometimes additional minerals like calcite. From a collector’s perspective, Uruguay’s best material looks intense under normal indoor lighting—one reason it’s so prized for display pieces and statement décor.

Near Artigas in northern Uruguay, amethyst mining is a major geological and economic feature of the region, rooted in the ancient volcanic rocks of the basaltic traps. Here, silica-rich fluids once permeated gas bubbles within the lava flows, ultimately forming countless cavities lined with quartz that later became the stunning amethyst crystals the area is known for today. Miners in the region work both open exposures and shallow pits where geode-bearing basalt is accessible, carefully extracting the geodes by hand or with light machinery to avoid damaging the delicate crystal interiors. Because these geodes form in layered sequences—often with an outer agate or chalcedony lining and a rich core of purple quartz—experienced miners use geological markers and local knowledge to find the pockets most likely to yield richly colored material.

The mining operations around Artigas combine traditional techniques and community-based efforts with small-scale commercial activity. Unlike large industrial mines, many of the workings are family-run or cooperative in nature, with local diggers and traders playing a central role in the supply chain. After extraction, the geodes are typically split and cleaned on site or nearby, then sorted for size, color saturation, and crystal quality before entering the global market. Uruguayan amethyst is prized for its deep violet hues and strong saturation, and the Artigas region remains one of the most important sources of high-grade amethyst geodes for collectors, jewelers, and décor markets worldwide. The largest amethyst geodes in the world come from the deposits near Artigas.

Brazil

Brazil is the world’s most prolific amethyst producers by volume and variety. Brazilian amethyst ranges from pale lilac to strong purple and occurs in both geodes and other quartz-bearing environments. Brazilian geodes can be enormous, and many of the classic “cathedral” showpieces in shops and collections trace back to Brazilian volcanic provinces. Brazilian material in general tends to be lighter colored, but with larger crystals the Uruguay amethyst.

Brazil is also famous for material that responds to heat treatment—historically feeding a large share of the citrine market through heated amethyst. Collectors also seek Brazilian specimens that show interesting zoning, large crystal points, and associated agate linings. Because Brazil produces such a wide spectrum, it’s a locality where “Brazilian amethyst” can mean many looks—so the best approach is to describe the color and habit rather than rely on the country name alone.

Las Vigas, Mexico

Las Vigas (Veracruz, Mexico) is renowned among collectors for distinctive, often slender and elegant quartz crystals, frequently with amethyst coloration or amethyst zoning. Rather than cathedral geodes, Las Vigas is known for specimen-style clusters and individual crystals that can show beautiful transparency, sharp terminations, and character-rich growth habits.

What makes Las Vigas stand out is the collector vibe: crystals can have a “clean, architectural” look, sometimes with phantoms, zoning, or subtle color gradients. The material appeals to people who love classic mineral aesthetics—well-formed points and clusters—rather than only the big geode décor style.

South Africa (Cactus Quartz / Spirit Quartz)

South Africa’s famous “cactus quartz” (often also called spirit quartz) is a texture phenomenon: a central quartz crystal (or cluster) becomes covered in a sparkling layer of tiny drusy crystals, creating a bristly, glittering surface—hence “cactus.” Many pieces are white to smoky, but amethyst-tinted examples are especially popular because the purple hue adds depth to the already dazzling surface.

These specimens are often collected for their overall look rather than perfect single-crystal faces. The appeal is maximal sparkle and otherworldly surface geometry—like a crystal that’s been “frosted” by quartz itself. In display lighting, cactus quartz can look alive, because every tiny crystal catches light at a different angle.

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Amethyst from the Democratic Republic of the Congo has gained increasing attention for its strong coloration and very large crystals. Material from the region commonly forms as clusters and crystal groups rather than large cathedral-style geodes, with well-developed points that display medium to deep purple hues. While not as historically famous as South American deposits, high-quality Congo amethyst can rival better-known sources in color and form, and its growing presence on the market has made it an increasingly important locality for modern collectors.

Thunder Bay, Ontario (Canada)

Thunder Bay amethyst is famous for its reddish iron staining and hematite inclusions, often giving crystals a warm, rusty contrast against the purple. This creates a distinct look compared with the cooler, saturated “cathedral” style from Uruguay. The result can be extremely photogenic: purple crystals with red-brown accents and a rugged, natural character.

Thunder Bay material is also celebrated for how it presents as a specimen mineral—clusters, points, and matrix pieces that feel like a slice of ancient geology rather than a polished décor product. Collectors often prize it for the locality identity: you can usually recognize Thunder Bay amethyst at a glance due to that iron-rich aesthetic.

North Carolina (USA)

North Carolina amethyst occurs in several geological contexts and is often collected as crystals and clusters rather than giant geodes. The state’s complex metamorphic and igneous history provides plenty of fractures and fluid pathways for quartz growth, and amethyst can appear as purple-tinted crystals in pockets, veins, and mineralized zones.

What makes North Carolina material appealing is the “local classic” status for U.S. collectors: it connects to a broader Appalachian mineral tradition—field collecting, pocket finds, and regional mineral localities. Pieces can vary widely in color intensity and habit, so North Carolina amethyst is often appreciated for individuality and provenance rather than one uniform signature look.

Special Forms and Varieties of Amethyst

Amethyst occurs in a wide range of crystal habits and mixed-color forms, many of which are considered distinct varieties by collectors due to their unusual growth patterns or visual characteristics. These special forms record subtle changes in chemistry, temperature, or growth conditions during crystallization, making them scientifically interesting as well as visually distinctive. Some varieties are defined by internal structure and zoning, while others are defined by dramatic crystal habits that differ from the classic single-point amethyst crystal.

Chevron Amethyst - is one of the most recognizable patterned varieties. It displays bold V-shaped or zigzag bands formed by alternating layers of purple amethyst and white or milky quartz. These patterns develop when crystal growth occurs in rhythmic stages, with slight shifts in chemistry or clarity between phases. Chevron amethyst is commonly cut into slabs, cabochons, and carvings where the natural banding creates striking, graphic designs that clearly reveal the stone’s growth history.

Amethyst scepters - are prized crystal forms in which a second generation of quartz grows on top of an earlier crystal, creating a thicker, darker purple “cap” on a narrower stem. This overgrowth happens when growth conditions change and later fluids deposit new quartz preferentially at the crystal tip. The result is a dramatic, top-heavy crystal that looks almost sculptural. Scepter amethyst is especially valued by mineral collectors because it clearly shows multiple growth episodes frozen in a single crystal.

Cactus amethyst - also commonly called spirit quartz, is best known from South Africa and is defined by its sparkling, drusy surface. In this form, a central quartz crystal becomes coated with thousands of tiny secondary crystals, creating a rough, spiny texture reminiscent of a cactus. While many cactus quartz specimens are white or smoky, amethyst-colored examples are particularly sought after, combining the vibrant purple hue with intense surface sparkle. The texture results from rapid nucleation of quartz crystals on an existing crystal surface rather than continued growth of a single crystal face.

Ametrine - is a unique quartz variety that naturally combines both amethyst (purple) and citrine (yellow) within the same crystal. This striking color contrast forms when different parts of the crystal experience different oxidation states of iron and subtle temperature gradients during growth. The boundary between purple and yellow can be sharp or gradual, creating dramatic visual effects when cut. Natural ametrine is relatively uncommon and most famously associated with deposits in Bolivia, making it one of the most distinctive and scientifically interesting mixed-color forms of quartz.

Cultural History and Uses of Amethyst

Amethyst’s cultural career is almost unmatched for a gemstone. It has been prized across civilizations not only for beauty, but for what people believed it did.

The “not drunk” stone: classical origins

The name amethyst traces back to ancient Greek, commonly linked to the idea of being “not intoxicated.” In classical stories, amethyst was associated with sobriety and clarity of mind. Whether or not anyone truly expected a gem to counteract wine, the belief anchored amethyst as a stone of moderation—an antidote to excess—at a time when symbolism and medicine often blurred together.

Greek and Roman artisans carved amethyst into engraved gems, seals, and jewelry. Because quartz is hard and takes a fine polish, it worked beautifully for intaglios and cameos. Amethyst’s regal color also gave it an air of prestige: purple dyes were expensive and status-coded in many ancient societies, and gemstones that echoed those hues naturally picked up similar associations.

Medieval to Renaissance: faith, power, and protection

In Europe, amethyst became entwined with Christian symbolism, especially among clergy. Purple carried themes of penitence, devotion, and authority, so amethyst often appeared in ecclesiastical rings and ornaments. Over time, it developed a reputation for protection—against not only intoxication but also temptation, negative thoughts, and “bad influences.” These ideas weren’t fringe; they were woven into the broader medieval worldview where stones, metals, and planets were thought to share sympathetic connections.

During the Renaissance, amethyst stayed fashionable in high jewelry and courtly adornment. It was valued as a “noble” gem alongside sapphire, ruby, emerald, and diamond—especially before vast modern deposits made it more accessible. The moment large-scale South American sources entered global trade, amethyst shifted from ultra-elite to widely loved—without losing its aura.

Modern uses: jewelry, décor, collecting, and symbolism

Today, amethyst is used across a wide range of applications that highlight both its beauty and durability. In jewelry, it is commonly cut into faceted stones, cabochons, beads, and carvings, with its Mohs hardness of 7 making it well suited for regular wear, provided it is protected from hard impacts and prolonged exposure to intense heat. Beyond jewelry, amethyst is a popular decorative stone, appearing as dramatic geode “cathedrals,” crystal clusters, bookends, spheres, and large statement pieces, where its visual impact scales effortlessly from small accents to room-anchoring displays.

Amethyst is also highly regarded among mineral collectors, who value it for its diverse crystal habits, color zoning, internal phantoms, inclusions such as hematite, and the distinctive characteristics tied to specific localities. In addition, it remains a meaningful choice for symbolic gifting, long associated with calm, balance, and mental clarity, and widely recognized as a February birthstone in modern traditions. Amethyst’s greatest cultural achievement is its ability to feel both ancient and contemporary at the same time—equally at home in historic crown jewels and on a modern minimalist shelf.

Caring for Amethyst: Light, Heat, and Long-Term Preservation

Amethyst is a relatively durable gemstone with a Mohs hardness of 7, making it well suited for jewelry and display, but its color requires thoughtful care. One of the most important considerations is light exposure. Prolonged exposure to direct sunlight or intense artificial light can cause some amethyst—especially pale lilac or lightly saturated material—to gradually fade over time. This happens because ultraviolet light can disrupt the color centers created by iron and natural irradiation within the crystal structure. While deeply colored amethyst is generally more resistant, no amethyst is completely immune to long-term UV exposure.

For this reason, amethyst specimens and jewelry are best displayed away from sunny windows, skylights, and strong display lighting. Rotating display pieces, using indirect lighting, or placing specimens in shaded areas can significantly slow fading. When storing amethyst, keep it in a dark or low-light environment, such as a cabinet, drawer, or boxed display. Jewelry should be stored separately to avoid scratching and kept away from heat sources, as excessive heat can also alter or destroy amethyst’s purple color, sometimes turning it yellow or brown.

Cleaning amethyst is straightforward but should be done gently. Warm water, mild soap, and a soft brush are usually sufficient for removing dust or oils. Avoid harsh chemicals, prolonged soaking, and ultrasonic cleaners—especially for specimens with fractures, inclusions, or delicate crystal points. With proper care and mindful light exposure, amethyst can retain its rich purple color and natural beauty for generations.

Reviews

Reviews