Stromatolites: The Earth's Oldest Fossils

Long before Earth had an oxygen-rich atmosphere or clear, modern oceans, life was already altering the planet in profound ways. The agents of that change were not plants or animals, but vast microbial communities living in shallow seas. These organisms were microscopic, yet their collective activity left behind some of the largest and most important biological structures ever preserved in rock: stromatolites.

Stromatolites are layered stone structures formed as microbial mats grew, trapped sediment, and precipitated minerals from seawater. Over time, these processes created domes, columns, ridges, and sheets that slowly rose from ancient seafloors. Although they appear simple, stromatolites record a turning point in Earth’s history—the moment when life began to influence atmospheric composition and ocean chemistry on a global scale.

In the earliest oceans, oxygen was rare, iron was abundant in dissolved form, and seawater chemistry was unlike anything seen today. Stromatolite-forming microbes lived at the boundary between sunlight, water, and sediment, where their metabolism subtly but continuously changed local chemical conditions. Over millions of years, those changes accumulated, helping transform Earth’s oceans and laying the groundwork for an atmosphere capable of supporting complex life.

Stromatolites exposed in the Cambrian-Aged Hoyt Limestone at Lester Park, near Saratoga Springs, New York.

Stromatolites are not fossils of individual organisms. Instead, they are fossils of microbial ecosystems. Each stromatolite represents countless generations of microorganisms—primarily bacteria—living together in cohesive mats on the seafloor.

These mats produced sticky organic substances that bound sediment grains together and slowed water flow, allowing particles to settle. At the same time, microbial metabolism altered the chemistry of the surrounding seawater, promoting the precipitation of carbonate minerals. As the mat grew, was buried, and regrew, it produced thin, repeating layers. Each layer marks a former living surface.

The result is a structure that preserves biological activity as rock. Stromatolites can be domed, columnar, conical, branching, or flat, depending on water depth, sediment supply, light availability, and seawater chemistry. Their layered internal structure reflects repeated interactions between life and environment rather than the remains of a single organism.

The formation of a stromatolite begins with a living microbial mat in shallow, sunlit water. These mats are not uniform. The upper layers are often dominated by photosynthetic microbes that capture sunlight and release oxygen, while deeper layers host organisms adapted to low-oxygen or oxygen-free conditions. Together, these communities create sharp chemical gradients within just a few millimeters.

As water flows across the mat, sediment grains are trapped by its sticky surface. At the same time, microbial metabolism alters local seawater chemistry. Photosynthesis can raise pH, while other metabolic processes influence alkalinity and carbonate saturation. These changes encourage minerals such as calcite or aragonite to precipitate within and around the mat.

When sediment or mineral crust buries the living surface, microbes recolonize the new top layer and the cycle begins again. Over long periods, repeated cycles of growth, trapping, and mineralization build a stromatolite layer by layer. The structure that remains is a durable record of biological activity interacting directly with ancient seawater chemistry.

The importance of stromatolites extends far beyond their visible, layered structures. The microbial communities that built them were deeply involved in one of the most profound transformations in Earth’s history: the long transition from an oxygen-poor planet to one with oxygenated oceans and atmosphere.

Stromatolites were already present during the Archean Eon, more than 3.5 billion years ago, when Earth’s atmosphere contained little to no free oxygen. During this time, seawater chemistry was dominated by dissolved iron and other reduced elements, and the oceans would likely have appeared greenish or murky by modern standards. Microbial communities living within stromatolite-forming mats included photosynthetic organisms that released oxygen as a byproduct of their metabolism, even though that oxygen could not yet accumulate in the environment.

Throughout much of the Archean, oxygen produced by these microbes was rapidly consumed by chemical reactions in the oceans. Dissolved iron combined with oxygen to form insoluble iron oxides, which settled to the seafloor and later became banded iron formations, some of the most distinctive sedimentary deposits in the geologic record. Stromatolites grew during this interval of intense chemical buffering, recording shallow marine environments in which biological oxygen production and chemical consumption were closely linked.

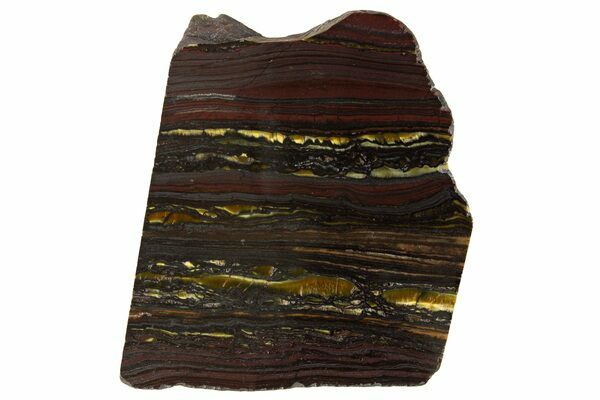

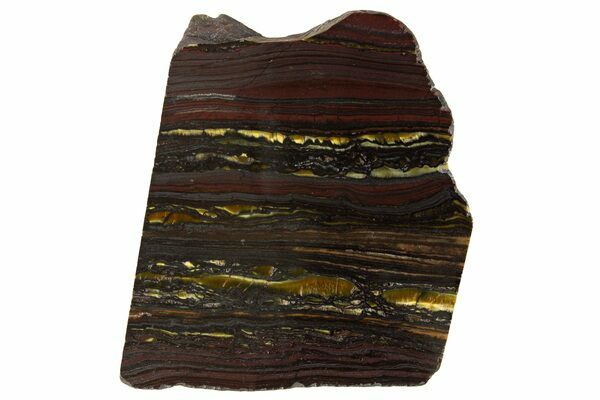

A polished section of Tiger Iron, a type of banded iron formation (BIF) formed through the action of oxygen producing stromatolites.

As Earth entered the Paleoproterozoic Era, roughly between 2.5 and 2.0 billion years ago, the balance began to shift. Over hundreds of millions of years, continued oxygen production gradually overwhelmed the ocean’s chemical sinks. Iron became less abundant in seawater, ocean chemistry stabilized, and oxygen began to persist not only locally around microbial mats but more broadly in the oceans.

This transition culminated in what is commonly known as the Great Oxidation Event, when oxygen first accumulated in Earth’s atmosphere in measurable amounts. Stromatolites were widespread during this time and continued to thrive in shallow marine environments, growing in seas that were undergoing fundamental chemical change. Their continued presence across this boundary reflects the persistence of microbial ecosystems even as global conditions shifted dramatically.

As oxygen became a permanent component of the atmosphere and surface oceans, entirely new biological possibilities emerged. Oxygen-enabled metabolisms supported more efficient energy use, paving the way for larger cells, more complex life cycles, and eventually multicellular organisms. Stromatolites, built by microbial communities operating at the interface of water, sediment, and chemistry, stand as one of the earliest and most enduring links between life and planetary-scale environmental change.

Rather than recording a single moment, stromatolites document a long, gradual transformation—one in which countless microbial communities, working layer by layer over immense spans of time, helped turn Earth into a world capable of sustaining complex life.

Some of the most important stromatolites known today occur in Archean rocks of Western Australia, where ancient seafloors have been remarkably well preserved. Within the Pilbara Craton, stromatolites provide a rare window into a world more than three billion years old, when microbial life was already capable of building large, organized structures.

At North Pole Dome, layered domical structures preserved within volcanic and sedimentary rocks have been interpreted as stromatolites approximately 3.4 to 3.5 billion years old. These structures occur in geological settings consistent with shallow marine environments and display lamination patterns that follow their external shape—an important hallmark of biological growth. Their association with sediments deposited in calm, sunlit waters strengthens the case that they were formed by microbial mats interacting with ancient seawater.

Nearby, the Strelley Pool Formation contains some of the most convincing early stromatolites known. These structures are similar in age and are exceptionally well preserved, showing clear domical morphologies and finely layered internal fabrics. The sedimentary context of Strelley Pool—interpreted as shallow marine carbonate deposits—closely matches environments where stromatolites form today. Because multiple lines of evidence converge, many researchers regard the Strelley Pool stromatolites as among the strongest demonstrations that microbial communities were already building complex structures early in Earth’s history.

Beyond Australia, even older candidates have been proposed, most notably from Greenland. In the Isua Greenstone Belt, structures dated to around 3.7 billion years old have been interpreted by some researchers as stromatolites, potentially pushing the origin of stromatolite formation—and large-scale microbial ecosystems—hundreds of millions of years further back in time. If confirmed, these would represent some of the earliest physical evidence for life interacting with Earth’s surface environments.

However, the Greenland structures remain highly controversial. The Isua rocks have experienced significant metamorphism, meaning they have been heated, compressed, and chemically altered over time. Such processes can distort original sedimentary features or generate layered and domed structures through non-biological mechanisms. Critics argue that the proposed Isua stromatolites may instead reflect deformation, mineral growth, or tectonic processes rather than microbial activity. Supporters counter that the structures’ shapes, spatial organization, and geological context are difficult to explain without biological involvement.

This debate highlights one of the central challenges in studying Earth’s earliest history: the older the rocks, the harder it becomes to separate biological signals from geological overprinting. As a result, scientists apply exceptionally high standards when evaluating ancient stromatolite claims. The most widely accepted examples are those where morphology, internal layering, sedimentary environment, and geochemical evidence all align in support of a biological origin.

Far from undermining stromatolite research, this ongoing debate reflects its rigor. Stromatolites sit at the boundary between life and rock, and the search for the oldest examples continues to refine our understanding of when—and how—life first began to shape Earth’s oceans and atmosphere.

The importance of stromatolites extends far beyond their visible, layered structures. The microbial communities that built them were deeply involved in one of the most profound transformations in Earth’s history: the long transition from an oxygen-poor planet to one with oxygenated oceans and atmosphere.

Stromatolites were already present during the Archean Eon, more than 3.5 billion years ago, when Earth’s atmosphere contained little to no free oxygen. During this time, seawater chemistry was dominated by dissolved iron and other reduced elements, and the oceans would likely have appeared greenish or murky by modern standards. Microbial communities living within stromatolite-forming mats included photosynthetic organisms that released oxygen as a byproduct of their metabolism, even though that oxygen could not yet accumulate in the environment.

Throughout much of the Archean, oxygen produced by these microbes was rapidly consumed by chemical reactions in the oceans. Dissolved iron combined with oxygen to form insoluble iron oxides, which settled to the seafloor and later became banded iron formations, some of the most distinctive sedimentary deposits in the geologic record. Stromatolites grew during this interval of intense chemical buffering, recording shallow marine environments in which biological oxygen production and chemical consumption were closely linked.

As Earth entered the Paleoproterozoic Era, roughly between 2.5 and 2.0 billion years ago, the balance began to shift. Over hundreds of millions of years, continued oxygen production gradually overwhelmed the ocean’s chemical sinks. Iron became less abundant in seawater, ocean chemistry stabilized, and oxygen began to persist not only locally around microbial mats but more broadly in the oceans.

This transition culminated in what is commonly known as the Great Oxidation Event, when oxygen first accumulated in Earth’s atmosphere in measurable amounts. Stromatolites were widespread during this time and continued to thrive in shallow marine environments, growing in seas that were undergoing fundamental chemical change. Their continued presence across this boundary reflects the persistence of microbial ecosystems even as global conditions shifted dramatically.

As oxygen became a permanent component of the atmosphere and surface oceans, entirely new biological possibilities emerged. Oxygen-enabled metabolisms supported more efficient energy use, paving the way for larger cells, more complex life cycles, and eventually multicellular organisms. Stromatolites, built by microbial communities operating at the interface of water, sediment, and chemistry, stand as one of the earliest and most enduring links between life and planetary-scale environmental change.

Rather than recording a single moment, stromatolites document a long, gradual transformation—one in which countless microbial communities, working layer by layer over immense spans of time, helped turn Earth into a world capable of sustaining complex life.

Many non-biological processes can produce layered or domed structures that mimic stromatolites. Chemical precipitation from seawater, rhythmic sedimentation, diagenetic mineral growth, and even deformation during burial can create convincing lookalikes.

These pseudo-stromatolites often lack the consistent growth patterns seen in true stromatolites. Their layers may cut across surrounding sediments or ignore external shape. In contrast, genuine stromatolites show lamination that wraps around growth forms, reflecting repeated biological colonization of a living surface. Distinguishing true stromatolites from impostors is especially critical in very old rocks, where claims of early life carry extraordinary significance.

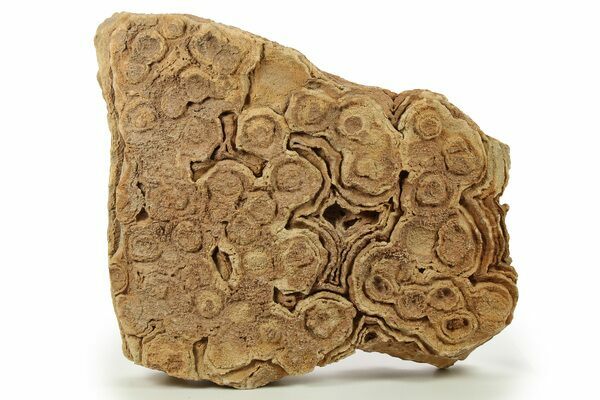

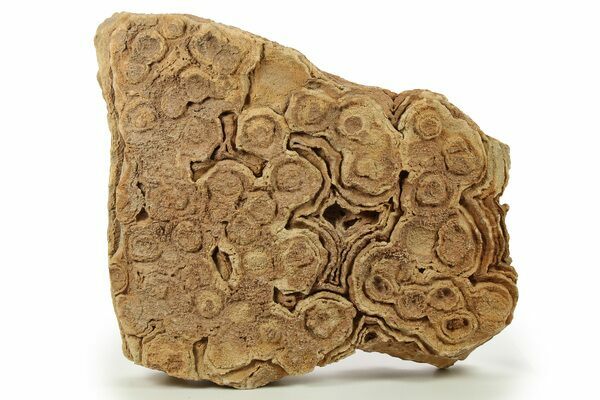

The Pseudo-Stromatolites from the Sahara desert, are formed through the precipitation of minerals (like barite) that cement sand grains together, rather than being built by microorganisms.

Stromatolites did not vanish with the rise of animals—they retreated. Today, they persist only in environments where grazing and burrowing organisms are naturally limited, offering rare glimpses into processes that once shaped much of Earth’s shallow seafloor. These modern examples are not relics in the sense of being unchanged, but they preserve the same fundamental interactions between microbial life, sediment, and water chemistry that defined stromatolites throughout Earth’s early history.

One of the most famous modern marine examples occurs in Shark Bay, Western Australia. Here, extensive stromatolite fields grow in shallow, hypersaline waters where elevated salinity discourages most grazing animals. The microbial mats trap carbonate sand and promote mineral precipitation, forming domes and ridges that closely resemble ancient fossil stromatolites. Shark Bay stromatolites have been studied for decades and remain one of the best natural laboratories for understanding how microbial communities build layered structures in marine environments.

Another marine example is found in the Exuma Cays of the Bahamas, where stromatolites grow in clear, shallow tidal channels. Unlike Shark Bay, these environments are not extremely saline, but strong currents and localized conditions reduce grazing pressure. The Bahamian stromatolites are particularly valuable because they demonstrate that stromatolite formation does not require extreme environments, only a balance between microbial growth and ecological disturbance.

Modern stromatolites also occur in freshwater environments, highlighting the versatility of microbial mat communities. In Lake Salda in Turkey, striking white carbonate stromatolites and microbialites form in alkaline waters rich in magnesium. These structures grow in shallow zones where chemistry favors rapid mineral precipitation, producing forms that closely resemble fossil stromatolites found in ancient lake deposits.

Freshwater stromatolites have also been documented in Lake Alchichica in Mexico, an alkaline volcanic lake where microbial communities build domed and columnar carbonate structures along the shoreline. These examples demonstrate that stromatolite formation is not restricted to marine settings and that similar biological and chemical processes can operate in lakes under the right conditions.

Modern stromatolites are especially valuable because they allow scientists to observe living microbial mats in action—tracking how layers form, how chemistry changes within millimeters of the mat surface, and how sediment becomes lithified over time. Although today’s oceans and lakes differ greatly from those of early Earth, these living examples help bridge the gap between ancient fossil structures and the biological processes that created them.

In a world dominated by animals, modern stromatolites survive only in ecological refuges. Yet their continued existence is a powerful reminder that microbial life still retains the ability to shape rock, alter water chemistry, and leave lasting records of its activity—just as it did at the dawn of life on Earth.

Stromatolites tell the story of life learning how to influence its environment. Built by microbes and preserved as stone, they record the gradual transformation of Earth’s oceans and atmosphere. Long before animals appeared, stromatolite-forming communities were already shaping the chemical foundation upon which all complex life depends.

They are among the most powerful reminders that even the smallest forms of life can leave an enduring imprint on a planet.

Stromatolites are layered stone structures formed as microbial mats grew, trapped sediment, and precipitated minerals from seawater. Over time, these processes created domes, columns, ridges, and sheets that slowly rose from ancient seafloors. Although they appear simple, stromatolites record a turning point in Earth’s history—the moment when life began to influence atmospheric composition and ocean chemistry on a global scale.

In the earliest oceans, oxygen was rare, iron was abundant in dissolved form, and seawater chemistry was unlike anything seen today. Stromatolite-forming microbes lived at the boundary between sunlight, water, and sediment, where their metabolism subtly but continuously changed local chemical conditions. Over millions of years, those changes accumulated, helping transform Earth’s oceans and laying the groundwork for an atmosphere capable of supporting complex life.

Stromatolites exposed in the Cambrian-Aged Hoyt Limestone at Lester Park, near Saratoga Springs, New York.

What Are Stromatolites?

Stromatolites are not fossils of individual organisms. Instead, they are fossils of microbial ecosystems. Each stromatolite represents countless generations of microorganisms—primarily bacteria—living together in cohesive mats on the seafloor.

These mats produced sticky organic substances that bound sediment grains together and slowed water flow, allowing particles to settle. At the same time, microbial metabolism altered the chemistry of the surrounding seawater, promoting the precipitation of carbonate minerals. As the mat grew, was buried, and regrew, it produced thin, repeating layers. Each layer marks a former living surface.

The result is a structure that preserves biological activity as rock. Stromatolites can be domed, columnar, conical, branching, or flat, depending on water depth, sediment supply, light availability, and seawater chemistry. Their layered internal structure reflects repeated interactions between life and environment rather than the remains of a single organism.

How Stromatolites Form: Microbes, Minerals, and Seawater Chemistry

The formation of a stromatolite begins with a living microbial mat in shallow, sunlit water. These mats are not uniform. The upper layers are often dominated by photosynthetic microbes that capture sunlight and release oxygen, while deeper layers host organisms adapted to low-oxygen or oxygen-free conditions. Together, these communities create sharp chemical gradients within just a few millimeters.

As water flows across the mat, sediment grains are trapped by its sticky surface. At the same time, microbial metabolism alters local seawater chemistry. Photosynthesis can raise pH, while other metabolic processes influence alkalinity and carbonate saturation. These changes encourage minerals such as calcite or aragonite to precipitate within and around the mat.

When sediment or mineral crust buries the living surface, microbes recolonize the new top layer and the cycle begins again. Over long periods, repeated cycles of growth, trapping, and mineralization build a stromatolite layer by layer. The structure that remains is a durable record of biological activity interacting directly with ancient seawater chemistry.

Stromatolites and the Rise of Oxygen

The importance of stromatolites extends far beyond their visible, layered structures. The microbial communities that built them were deeply involved in one of the most profound transformations in Earth’s history: the long transition from an oxygen-poor planet to one with oxygenated oceans and atmosphere.

Stromatolites were already present during the Archean Eon, more than 3.5 billion years ago, when Earth’s atmosphere contained little to no free oxygen. During this time, seawater chemistry was dominated by dissolved iron and other reduced elements, and the oceans would likely have appeared greenish or murky by modern standards. Microbial communities living within stromatolite-forming mats included photosynthetic organisms that released oxygen as a byproduct of their metabolism, even though that oxygen could not yet accumulate in the environment.

Throughout much of the Archean, oxygen produced by these microbes was rapidly consumed by chemical reactions in the oceans. Dissolved iron combined with oxygen to form insoluble iron oxides, which settled to the seafloor and later became banded iron formations, some of the most distinctive sedimentary deposits in the geologic record. Stromatolites grew during this interval of intense chemical buffering, recording shallow marine environments in which biological oxygen production and chemical consumption were closely linked.

A polished section of Tiger Iron, a type of banded iron formation (BIF) formed through the action of oxygen producing stromatolites.

As Earth entered the Paleoproterozoic Era, roughly between 2.5 and 2.0 billion years ago, the balance began to shift. Over hundreds of millions of years, continued oxygen production gradually overwhelmed the ocean’s chemical sinks. Iron became less abundant in seawater, ocean chemistry stabilized, and oxygen began to persist not only locally around microbial mats but more broadly in the oceans.

This transition culminated in what is commonly known as the Great Oxidation Event, when oxygen first accumulated in Earth’s atmosphere in measurable amounts. Stromatolites were widespread during this time and continued to thrive in shallow marine environments, growing in seas that were undergoing fundamental chemical change. Their continued presence across this boundary reflects the persistence of microbial ecosystems even as global conditions shifted dramatically.

As oxygen became a permanent component of the atmosphere and surface oceans, entirely new biological possibilities emerged. Oxygen-enabled metabolisms supported more efficient energy use, paving the way for larger cells, more complex life cycles, and eventually multicellular organisms. Stromatolites, built by microbial communities operating at the interface of water, sediment, and chemistry, stand as one of the earliest and most enduring links between life and planetary-scale environmental change.

Rather than recording a single moment, stromatolites document a long, gradual transformation—one in which countless microbial communities, working layer by layer over immense spans of time, helped turn Earth into a world capable of sustaining complex life.

The Oldest Stromatolites and the Search for Earth’s Earliest Life

Some of the most important stromatolites known today occur in Archean rocks of Western Australia, where ancient seafloors have been remarkably well preserved. Within the Pilbara Craton, stromatolites provide a rare window into a world more than three billion years old, when microbial life was already capable of building large, organized structures.

At North Pole Dome, layered domical structures preserved within volcanic and sedimentary rocks have been interpreted as stromatolites approximately 3.4 to 3.5 billion years old. These structures occur in geological settings consistent with shallow marine environments and display lamination patterns that follow their external shape—an important hallmark of biological growth. Their association with sediments deposited in calm, sunlit waters strengthens the case that they were formed by microbial mats interacting with ancient seawater.

Nearby, the Strelley Pool Formation contains some of the most convincing early stromatolites known. These structures are similar in age and are exceptionally well preserved, showing clear domical morphologies and finely layered internal fabrics. The sedimentary context of Strelley Pool—interpreted as shallow marine carbonate deposits—closely matches environments where stromatolites form today. Because multiple lines of evidence converge, many researchers regard the Strelley Pool stromatolites as among the strongest demonstrations that microbial communities were already building complex structures early in Earth’s history.

Beyond Australia, even older candidates have been proposed, most notably from Greenland. In the Isua Greenstone Belt, structures dated to around 3.7 billion years old have been interpreted by some researchers as stromatolites, potentially pushing the origin of stromatolite formation—and large-scale microbial ecosystems—hundreds of millions of years further back in time. If confirmed, these would represent some of the earliest physical evidence for life interacting with Earth’s surface environments.

However, the Greenland structures remain highly controversial. The Isua rocks have experienced significant metamorphism, meaning they have been heated, compressed, and chemically altered over time. Such processes can distort original sedimentary features or generate layered and domed structures through non-biological mechanisms. Critics argue that the proposed Isua stromatolites may instead reflect deformation, mineral growth, or tectonic processes rather than microbial activity. Supporters counter that the structures’ shapes, spatial organization, and geological context are difficult to explain without biological involvement.

This debate highlights one of the central challenges in studying Earth’s earliest history: the older the rocks, the harder it becomes to separate biological signals from geological overprinting. As a result, scientists apply exceptionally high standards when evaluating ancient stromatolite claims. The most widely accepted examples are those where morphology, internal layering, sedimentary environment, and geochemical evidence all align in support of a biological origin.

Far from undermining stromatolite research, this ongoing debate reflects its rigor. Stromatolites sit at the boundary between life and rock, and the search for the oldest examples continues to refine our understanding of when—and how—life first began to shape Earth’s oceans and atmosphere.

The importance of stromatolites extends far beyond their visible, layered structures. The microbial communities that built them were deeply involved in one of the most profound transformations in Earth’s history: the long transition from an oxygen-poor planet to one with oxygenated oceans and atmosphere.

Stromatolites were already present during the Archean Eon, more than 3.5 billion years ago, when Earth’s atmosphere contained little to no free oxygen. During this time, seawater chemistry was dominated by dissolved iron and other reduced elements, and the oceans would likely have appeared greenish or murky by modern standards. Microbial communities living within stromatolite-forming mats included photosynthetic organisms that released oxygen as a byproduct of their metabolism, even though that oxygen could not yet accumulate in the environment.

Throughout much of the Archean, oxygen produced by these microbes was rapidly consumed by chemical reactions in the oceans. Dissolved iron combined with oxygen to form insoluble iron oxides, which settled to the seafloor and later became banded iron formations, some of the most distinctive sedimentary deposits in the geologic record. Stromatolites grew during this interval of intense chemical buffering, recording shallow marine environments in which biological oxygen production and chemical consumption were closely linked.

As Earth entered the Paleoproterozoic Era, roughly between 2.5 and 2.0 billion years ago, the balance began to shift. Over hundreds of millions of years, continued oxygen production gradually overwhelmed the ocean’s chemical sinks. Iron became less abundant in seawater, ocean chemistry stabilized, and oxygen began to persist not only locally around microbial mats but more broadly in the oceans.

This transition culminated in what is commonly known as the Great Oxidation Event, when oxygen first accumulated in Earth’s atmosphere in measurable amounts. Stromatolites were widespread during this time and continued to thrive in shallow marine environments, growing in seas that were undergoing fundamental chemical change. Their continued presence across this boundary reflects the persistence of microbial ecosystems even as global conditions shifted dramatically.

As oxygen became a permanent component of the atmosphere and surface oceans, entirely new biological possibilities emerged. Oxygen-enabled metabolisms supported more efficient energy use, paving the way for larger cells, more complex life cycles, and eventually multicellular organisms. Stromatolites, built by microbial communities operating at the interface of water, sediment, and chemistry, stand as one of the earliest and most enduring links between life and planetary-scale environmental change.

Rather than recording a single moment, stromatolites document a long, gradual transformation—one in which countless microbial communities, working layer by layer over immense spans of time, helped turn Earth into a world capable of sustaining complex life.

Pseudo-Stromatolites: False Signals in the Rock Record

Many non-biological processes can produce layered or domed structures that mimic stromatolites. Chemical precipitation from seawater, rhythmic sedimentation, diagenetic mineral growth, and even deformation during burial can create convincing lookalikes.

These pseudo-stromatolites often lack the consistent growth patterns seen in true stromatolites. Their layers may cut across surrounding sediments or ignore external shape. In contrast, genuine stromatolites show lamination that wraps around growth forms, reflecting repeated biological colonization of a living surface. Distinguishing true stromatolites from impostors is especially critical in very old rocks, where claims of early life carry extraordinary significance.

The Pseudo-Stromatolites from the Sahara desert, are formed through the precipitation of minerals (like barite) that cement sand grains together, rather than being built by microorganisms.

Stromatolites Today: Living Survivors of an Ancient Way of Life

Stromatolites did not vanish with the rise of animals—they retreated. Today, they persist only in environments where grazing and burrowing organisms are naturally limited, offering rare glimpses into processes that once shaped much of Earth’s shallow seafloor. These modern examples are not relics in the sense of being unchanged, but they preserve the same fundamental interactions between microbial life, sediment, and water chemistry that defined stromatolites throughout Earth’s early history.

One of the most famous modern marine examples occurs in Shark Bay, Western Australia. Here, extensive stromatolite fields grow in shallow, hypersaline waters where elevated salinity discourages most grazing animals. The microbial mats trap carbonate sand and promote mineral precipitation, forming domes and ridges that closely resemble ancient fossil stromatolites. Shark Bay stromatolites have been studied for decades and remain one of the best natural laboratories for understanding how microbial communities build layered structures in marine environments.

Another marine example is found in the Exuma Cays of the Bahamas, where stromatolites grow in clear, shallow tidal channels. Unlike Shark Bay, these environments are not extremely saline, but strong currents and localized conditions reduce grazing pressure. The Bahamian stromatolites are particularly valuable because they demonstrate that stromatolite formation does not require extreme environments, only a balance between microbial growth and ecological disturbance.

Modern stromatolites also occur in freshwater environments, highlighting the versatility of microbial mat communities. In Lake Salda in Turkey, striking white carbonate stromatolites and microbialites form in alkaline waters rich in magnesium. These structures grow in shallow zones where chemistry favors rapid mineral precipitation, producing forms that closely resemble fossil stromatolites found in ancient lake deposits.

Freshwater stromatolites have also been documented in Lake Alchichica in Mexico, an alkaline volcanic lake where microbial communities build domed and columnar carbonate structures along the shoreline. These examples demonstrate that stromatolite formation is not restricted to marine settings and that similar biological and chemical processes can operate in lakes under the right conditions.

Modern stromatolites are especially valuable because they allow scientists to observe living microbial mats in action—tracking how layers form, how chemistry changes within millimeters of the mat surface, and how sediment becomes lithified over time. Although today’s oceans and lakes differ greatly from those of early Earth, these living examples help bridge the gap between ancient fossil structures and the biological processes that created them.

In a world dominated by animals, modern stromatolites survive only in ecological refuges. Yet their continued existence is a powerful reminder that microbial life still retains the ability to shape rock, alter water chemistry, and leave lasting records of its activity—just as it did at the dawn of life on Earth.

Layer by Layer, a Planet Changed

Stromatolites tell the story of life learning how to influence its environment. Built by microbes and preserved as stone, they record the gradual transformation of Earth’s oceans and atmosphere. Long before animals appeared, stromatolite-forming communities were already shaping the chemical foundation upon which all complex life depends.

They are among the most powerful reminders that even the smallest forms of life can leave an enduring imprint on a planet.

Reviews

Reviews