The Evolution Of Fish

Fish are among the most successful and enduring groups of vertebrates on Earth, with a history that stretches back more than 500 million years to the early Cambrian oceans. Their story begins with simple, jawless animals that lacked fins, teeth, or true bones, yet possessed a defining innovation—the backbone. Over time, evolutionary advances such as jaws, paired fins, and stronger skeletons transformed fish into active swimmers and predators, driving an explosion of diversity. From armored placoderms to sharks and ray-finned fishes, these adaptations reshaped ancient seas and established the basic body plans still seen in modern vertebrates.

Crucially, some ancient fishes adapted to life in shallow, low-oxygen environments by developing lungs and sturdy, limb-like fins. These lobe-finned fishes gave rise to the first vertebrates capable of moving onto land, laying the groundwork for amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals, and eventually humans. In this way, the evolutionary history of fish is far more than a story of life in water—it is the foundation of all vertebrate life on Earth, including our own.

In scientific terms, “fish” describes a broad collection of aquatic vertebrates that share a few key features:

Chordates — they possess a backbone or a supportive notochord.

Aquatic lifestyles — living primarily in water.

Gills — specialized organs to extract oxygen from water.

Fins — paired and median appendages used for locomotion.

Ectothermic metabolism — their body temperature varies with the environment.

But fish aren’t a single evolutionary group in the strictest sense. Instead, they represent multiple lineages that share similar aquatic adaptations.

The first organisms that can be described as primitive fish appear in the fossil record around 530 million years ago, during the early Cambrian Period. These early vertebrates looked nothing like modern fish. They lacked jaws, true bones, and paired fins, and instead relied on a flexible internal support structure called a notochord rather than a fully developed позвоночник (spinal column). Simple gills allowed them to extract oxygen from seawater, and their bodies were small, soft, and streamlined—well suited for life in ancient oceans dominated by invertebrates.

One of the best-known examples of these early fishes is Haikouichthys, a tiny, eel-like animal that represents a major evolutionary milestone. In addition to possessing a notochord, Haikouichthys displayed several revolutionary traits that set the stage for all later vertebrates. Its body was bilaterally symmetric, with a clear left and right side, and it showed early cephalization—meaning its head was distinct from its tail. Within this defined head region were two simple eyes and a mouth, allowing it to sense and respond to its environment in more complex ways. These seemingly modest features marked a profound shift in animal evolution, establishing the basic vertebrate body plan that would eventually lead to fish, amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and humans.

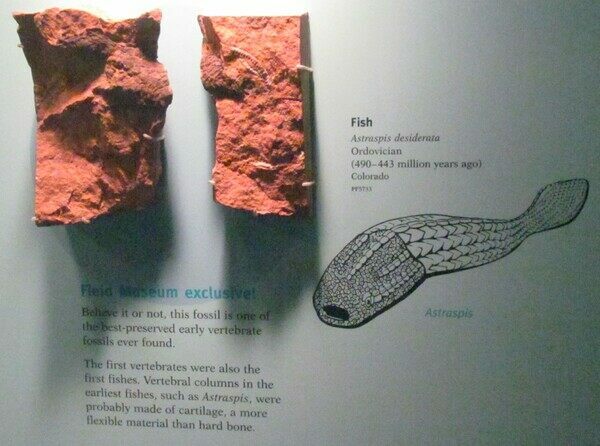

During the Ordovician Period, around 480 million years ago, vertebrate evolution took a major leap forward as the spinal column began to resemble its modern form and the first true fish appeared in the fossil record. These early fishes were still jawless, but they were far more advanced than their Cambrian ancestors. One of the most significant developments of this time was the emergence of heavy external armor. Bony plates formed over the head and thorax, providing protection from predators and environmental hazards. A well-known example is Astraspis, a jawless fish covered in distinctive star-shaped scales, which represents one of the earliest attempts at a mineralized skeleton in vertebrate history.

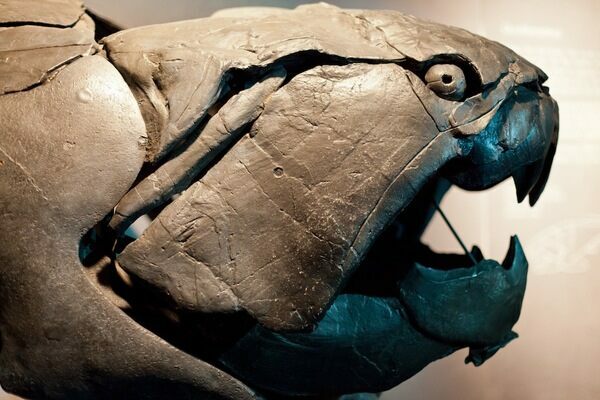

Later in the Ordovician, a revolutionary innovation appeared: bony jaws. This development transformed fish from relatively passive feeders into active, formidable predators, dramatically altering marine ecosystems. Around this time, the fish lineage split into two major evolutionary branches—the placoderms and the acanthodians. Placoderms, or “armored fishes,” continued refining bony skeletons and ultimately gave rise to bony fishes and all other vertebrates, including those that would later move onto land. Acanthodians, often called “spiny sharks,” represent a fascinating transitional group that combined traits of both bony fish and sharks. Their streamlined, shark-like bodies were reinforced with prominent fin spines, while their bony scales closely resembled those of modern garfish. Together, these groups illustrate a critical turning point in vertebrate evolution, when structure, armor, and feeding strategies became increasingly sophisticated.

Late in the Silurian Period, as marine ecosystems became increasingly complex, the major fish lineages diverged once again in a way that shaped the future of vertebrate life. The placoderms branched off into the Osteichthyes, or bony fishes, while the acanthodians split into the Chondrichthyes, the lineage that would give rise to modern sharks and rays. Osteichthyes developed lightweight but strong bony skeletons that allowed for greater versatility and would eventually dominate most aquatic environments. Meanwhile, the Chondrichthyes evolved skeletons made of cartilage rather than bone, a design that favored speed, agility, and efficient swimming.

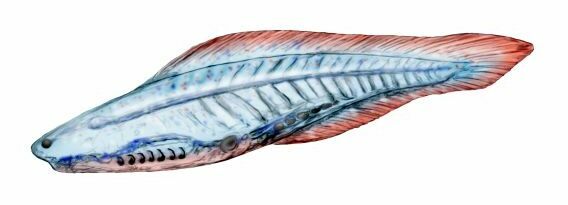

As the Silurian transitioned into the Devonian Period—often called the “Age of Fishes”—chondrichthyans rapidly diversified into increasingly fast, agile, and aggressive predators. Their evolutionary success likely placed intense pressure on other fish groups through both competition for food and direct predation. By the end of the Devonian, the once-dominant placoderms had disappeared entirely from the fossil record. At the same time, the Devonian witnessed the emergence of the first lobe-finned fishes, a crucial evolutionary innovation. Unlike ray-finned fishes, which rely on thin bone rays to support their fins, lobe-finned fishes possessed fleshy, muscular lobes reinforced by internal bones. Modern examples such as the coelacanth provide a glimpse of this ancient design, which would ultimately give rise to the first vertebrates capable of venturing onto land.

With the extinction of the placoderms by the end of the Devonian Period, sharks were freed from one of their greatest competitors and underwent a major evolutionary radiation. This surge in diversity led to the emergence of many unusual and highly specialized forms as sharks experimented with new body shapes, feeding strategies, and ecological roles. During this time, some lineages developed striking and sometimes bizarre adaptations. One such group, the family Stethacanthidae, evolved a highly distinctive dorsal fin that resembled a flattened brush or anvil rather than a typical triangular fin. This structure was wider than it was tall and covered with specialized denticles, and while it is widely believed to have played a role in mating displays or species recognition, it may also have served defensive or hydrodynamic functions.

This period of innovation continued into the Carboniferous and early Permian, when sharks occupied a wide range of marine niches and became dominant predators in many ecosystems. However, this success was abruptly interrupted at the end of the Permian Period by the Permian–Triassic extinction event, the most catastrophic mass extinction in Earth’s history. During this event, an estimated 90 to 95 percent of all marine species vanished due to dramatic environmental changes, including ocean acidification, widespread anoxia, and extreme climate shifts. Among the groups that did not survive this crisis were the acanthodians, or spiny sharks, which disappeared entirely from the fossil record. Their extinction marked the end of an important early experiment in shark evolution, clearing the way for the rise of more modern shark lineages in the Triassic seas.

The early Triassic Period was largely a time of recovery for fish following the devastation of the Permian–Triassic extinction. Marine ecosystems were severely depleted, and the fishes that survived tended to share similar body shapes and lifestyles. This uniformity likely reflects the fact that most new species evolved from a very small number of surviving families, resulting in conservative, generalized forms well suited to unstable environments. Over time, as conditions improved and ecosystems stabilized, these early Triassic fishes gradually diversified. By the end of the Triassic, bony fishes underwent a major evolutionary radiation comparable to the shark radiation of the Devonian, establishing many of the structural and ecological foundations seen in modern fish groups.

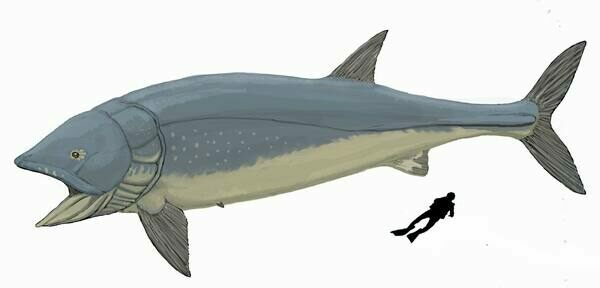

This progress was interrupted by another major extinction event at the boundary between the Triassic and Jurassic periods, during which roughly 70 percent of all fish species disappeared. Despite this setback, the Jurassic Period that followed saw a dramatic increase in both diversity and size among bony fishes. New predatory lineages emerged, including the family Ichthyodectidae, fast-swimming carnivorous fishes that occupied top positions in marine food webs. At the same time, even filter-feeding fishes evolved to enormous proportions. The most spectacular example is Leedsichthys, a gentle giant estimated to have reached lengths of up to 50 feet, making it one of the largest bony fishes—and one of the largest fish of any kind—to have ever lived.

One school of thought is that this is the result of the open environmental niches left by the extinction event. Another suggests the great size increase in fish is due to the existence of large reptiles like, Plesiosaurs, Pliosaurs, and marine crocodiles that were now common in the world’s water bodies.

During the Cretaceous Period and continuing into the Cenozoic Era we begin to see more and more of the closest ancestors of modern fish. Some of the more charismatic predators of their day, appear in the fossil record as well. True sturgeon appear, along with sharks like Cretoxyrhina mantelli, the Ginsu Shark appear in the jurassic alongside the giant bony fish Xiphactinus.

Even across the KT extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs and seventy five percent of life on land, the fish species thrived. It is estimated that eighty percent of cartilaginous fish (sharks, rays, and chimera) survived the event and up to ninety five percent of bony fish survived. The ray finned fish experience their own expansion of species and sizes shortly after the KT event. It is thought that this is due to the extinction of ammonites with whom they had to compete for food and other resources.

Over the last 50 million years, fish have continued to expand, diversify, and refine their forms into the astonishing variety we recognize in today’s oceans, rivers, and lakes. Following the extinction of the dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous, many ecological niches were suddenly left vacant, allowing fishes—especially bony fishes—to rapidly adapt and specialize. During this time, modern groups such as tunas, reef fishes, flatfishes, eels, and many deep-sea lineages emerged, each evolving body shapes and behaviors finely tuned to their environments. Streamlined torpedo shapes favored open-ocean speed, flattened bodies suited life on the seafloor, and highly compressed forms allowed precise maneuvering through coral reefs.

These changes were driven by a combination of environmental shifts, predator–prey interactions, and increasingly complex ecosystems. Advances in jaw mechanics, fin placement, sensory systems, and swimming efficiency allowed fish to exploit nearly every aquatic habitat on Earth, from sunlit coral reefs to the deepest trenches. By the time humans appeared, fish had already perfected an extraordinary range of solutions to life in water. The diversity of shapes, sizes, and lifestyles seen in modern fish is the culmination of hundreds of millions of years of evolutionary experimentation—an ongoing process that continues to shape the world’s aquatic ecosystems today.

Crucially, some ancient fishes adapted to life in shallow, low-oxygen environments by developing lungs and sturdy, limb-like fins. These lobe-finned fishes gave rise to the first vertebrates capable of moving onto land, laying the groundwork for amphibians, reptiles, birds, mammals, and eventually humans. In this way, the evolutionary history of fish is far more than a story of life in water—it is the foundation of all vertebrate life on Earth, including our own.

What Are Fish?

In scientific terms, “fish” describes a broad collection of aquatic vertebrates that share a few key features:

But fish aren’t a single evolutionary group in the strictest sense. Instead, they represent multiple lineages that share similar aquatic adaptations.

How Did Fish Evolve?

The first organisms that can be described as primitive fish appear in the fossil record around 530 million years ago, during the early Cambrian Period. These early vertebrates looked nothing like modern fish. They lacked jaws, true bones, and paired fins, and instead relied on a flexible internal support structure called a notochord rather than a fully developed позвоночник (spinal column). Simple gills allowed them to extract oxygen from seawater, and their bodies were small, soft, and streamlined—well suited for life in ancient oceans dominated by invertebrates.

One of the best-known examples of these early fishes is Haikouichthys, a tiny, eel-like animal that represents a major evolutionary milestone. In addition to possessing a notochord, Haikouichthys displayed several revolutionary traits that set the stage for all later vertebrates. Its body was bilaterally symmetric, with a clear left and right side, and it showed early cephalization—meaning its head was distinct from its tail. Within this defined head region were two simple eyes and a mouth, allowing it to sense and respond to its environment in more complex ways. These seemingly modest features marked a profound shift in animal evolution, establishing the basic vertebrate body plan that would eventually lead to fish, amphibians, reptiles, mammals, and humans.

During the Ordovician Period, around 480 million years ago, vertebrate evolution took a major leap forward as the spinal column began to resemble its modern form and the first true fish appeared in the fossil record. These early fishes were still jawless, but they were far more advanced than their Cambrian ancestors. One of the most significant developments of this time was the emergence of heavy external armor. Bony plates formed over the head and thorax, providing protection from predators and environmental hazards. A well-known example is Astraspis, a jawless fish covered in distinctive star-shaped scales, which represents one of the earliest attempts at a mineralized skeleton in vertebrate history.

Later in the Ordovician, a revolutionary innovation appeared: bony jaws. This development transformed fish from relatively passive feeders into active, formidable predators, dramatically altering marine ecosystems. Around this time, the fish lineage split into two major evolutionary branches—the placoderms and the acanthodians. Placoderms, or “armored fishes,” continued refining bony skeletons and ultimately gave rise to bony fishes and all other vertebrates, including those that would later move onto land. Acanthodians, often called “spiny sharks,” represent a fascinating transitional group that combined traits of both bony fish and sharks. Their streamlined, shark-like bodies were reinforced with prominent fin spines, while their bony scales closely resembled those of modern garfish. Together, these groups illustrate a critical turning point in vertebrate evolution, when structure, armor, and feeding strategies became increasingly sophisticated.

Late in the Silurian Period, as marine ecosystems became increasingly complex, the major fish lineages diverged once again in a way that shaped the future of vertebrate life. The placoderms branched off into the Osteichthyes, or bony fishes, while the acanthodians split into the Chondrichthyes, the lineage that would give rise to modern sharks and rays. Osteichthyes developed lightweight but strong bony skeletons that allowed for greater versatility and would eventually dominate most aquatic environments. Meanwhile, the Chondrichthyes evolved skeletons made of cartilage rather than bone, a design that favored speed, agility, and efficient swimming.

As the Silurian transitioned into the Devonian Period—often called the “Age of Fishes”—chondrichthyans rapidly diversified into increasingly fast, agile, and aggressive predators. Their evolutionary success likely placed intense pressure on other fish groups through both competition for food and direct predation. By the end of the Devonian, the once-dominant placoderms had disappeared entirely from the fossil record. At the same time, the Devonian witnessed the emergence of the first lobe-finned fishes, a crucial evolutionary innovation. Unlike ray-finned fishes, which rely on thin bone rays to support their fins, lobe-finned fishes possessed fleshy, muscular lobes reinforced by internal bones. Modern examples such as the coelacanth provide a glimpse of this ancient design, which would ultimately give rise to the first vertebrates capable of venturing onto land.

With the extinction of the placoderms by the end of the Devonian Period, sharks were freed from one of their greatest competitors and underwent a major evolutionary radiation. This surge in diversity led to the emergence of many unusual and highly specialized forms as sharks experimented with new body shapes, feeding strategies, and ecological roles. During this time, some lineages developed striking and sometimes bizarre adaptations. One such group, the family Stethacanthidae, evolved a highly distinctive dorsal fin that resembled a flattened brush or anvil rather than a typical triangular fin. This structure was wider than it was tall and covered with specialized denticles, and while it is widely believed to have played a role in mating displays or species recognition, it may also have served defensive or hydrodynamic functions.

This period of innovation continued into the Carboniferous and early Permian, when sharks occupied a wide range of marine niches and became dominant predators in many ecosystems. However, this success was abruptly interrupted at the end of the Permian Period by the Permian–Triassic extinction event, the most catastrophic mass extinction in Earth’s history. During this event, an estimated 90 to 95 percent of all marine species vanished due to dramatic environmental changes, including ocean acidification, widespread anoxia, and extreme climate shifts. Among the groups that did not survive this crisis were the acanthodians, or spiny sharks, which disappeared entirely from the fossil record. Their extinction marked the end of an important early experiment in shark evolution, clearing the way for the rise of more modern shark lineages in the Triassic seas.

The early Triassic Period was largely a time of recovery for fish following the devastation of the Permian–Triassic extinction. Marine ecosystems were severely depleted, and the fishes that survived tended to share similar body shapes and lifestyles. This uniformity likely reflects the fact that most new species evolved from a very small number of surviving families, resulting in conservative, generalized forms well suited to unstable environments. Over time, as conditions improved and ecosystems stabilized, these early Triassic fishes gradually diversified. By the end of the Triassic, bony fishes underwent a major evolutionary radiation comparable to the shark radiation of the Devonian, establishing many of the structural and ecological foundations seen in modern fish groups.

This progress was interrupted by another major extinction event at the boundary between the Triassic and Jurassic periods, during which roughly 70 percent of all fish species disappeared. Despite this setback, the Jurassic Period that followed saw a dramatic increase in both diversity and size among bony fishes. New predatory lineages emerged, including the family Ichthyodectidae, fast-swimming carnivorous fishes that occupied top positions in marine food webs. At the same time, even filter-feeding fishes evolved to enormous proportions. The most spectacular example is Leedsichthys, a gentle giant estimated to have reached lengths of up to 50 feet, making it one of the largest bony fishes—and one of the largest fish of any kind—to have ever lived.

One school of thought is that this is the result of the open environmental niches left by the extinction event. Another suggests the great size increase in fish is due to the existence of large reptiles like, Plesiosaurs, Pliosaurs, and marine crocodiles that were now common in the world’s water bodies.

During the Cretaceous Period and continuing into the Cenozoic Era we begin to see more and more of the closest ancestors of modern fish. Some of the more charismatic predators of their day, appear in the fossil record as well. True sturgeon appear, along with sharks like Cretoxyrhina mantelli, the Ginsu Shark appear in the jurassic alongside the giant bony fish Xiphactinus.

Even across the KT extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs and seventy five percent of life on land, the fish species thrived. It is estimated that eighty percent of cartilaginous fish (sharks, rays, and chimera) survived the event and up to ninety five percent of bony fish survived. The ray finned fish experience their own expansion of species and sizes shortly after the KT event. It is thought that this is due to the extinction of ammonites with whom they had to compete for food and other resources.

Over the last 50 million years, fish have continued to expand, diversify, and refine their forms into the astonishing variety we recognize in today’s oceans, rivers, and lakes. Following the extinction of the dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous, many ecological niches were suddenly left vacant, allowing fishes—especially bony fishes—to rapidly adapt and specialize. During this time, modern groups such as tunas, reef fishes, flatfishes, eels, and many deep-sea lineages emerged, each evolving body shapes and behaviors finely tuned to their environments. Streamlined torpedo shapes favored open-ocean speed, flattened bodies suited life on the seafloor, and highly compressed forms allowed precise maneuvering through coral reefs.

These changes were driven by a combination of environmental shifts, predator–prey interactions, and increasingly complex ecosystems. Advances in jaw mechanics, fin placement, sensory systems, and swimming efficiency allowed fish to exploit nearly every aquatic habitat on Earth, from sunlit coral reefs to the deepest trenches. By the time humans appeared, fish had already perfected an extraordinary range of solutions to life in water. The diversity of shapes, sizes, and lifestyles seen in modern fish is the culmination of hundreds of millions of years of evolutionary experimentation—an ongoing process that continues to shape the world’s aquatic ecosystems today.

Reviews

Reviews